Review: The Monkees in Rhino High Fidelity

1967’s Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd. is cut directly from the master—for the very first time.

It makes perfect sense that the Rhino High Fidelity series take on a Monkees album. No, really, it does. In the 1980s, Rhino Records made their bones on Monkees reissues, when the TV stars-turned-recording artists experienced a major revival after their ’60s show reran on MTV and Nickelodeon. The label, even before it was fully acquired by Warner, has been utterly devoted to the group’s catalog, issuing multiple box sets and deluxe editions of their nine initial albums over the years. In fact, the penultimate album (save the unfortunate Changes) to receive Rhino’s super-deluxe treatment, Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd., has just been unleashed in a 4-CD box set with all the trimmings, making it the perfect time for a Rhino High Fidelity vinyl version to accompany it.

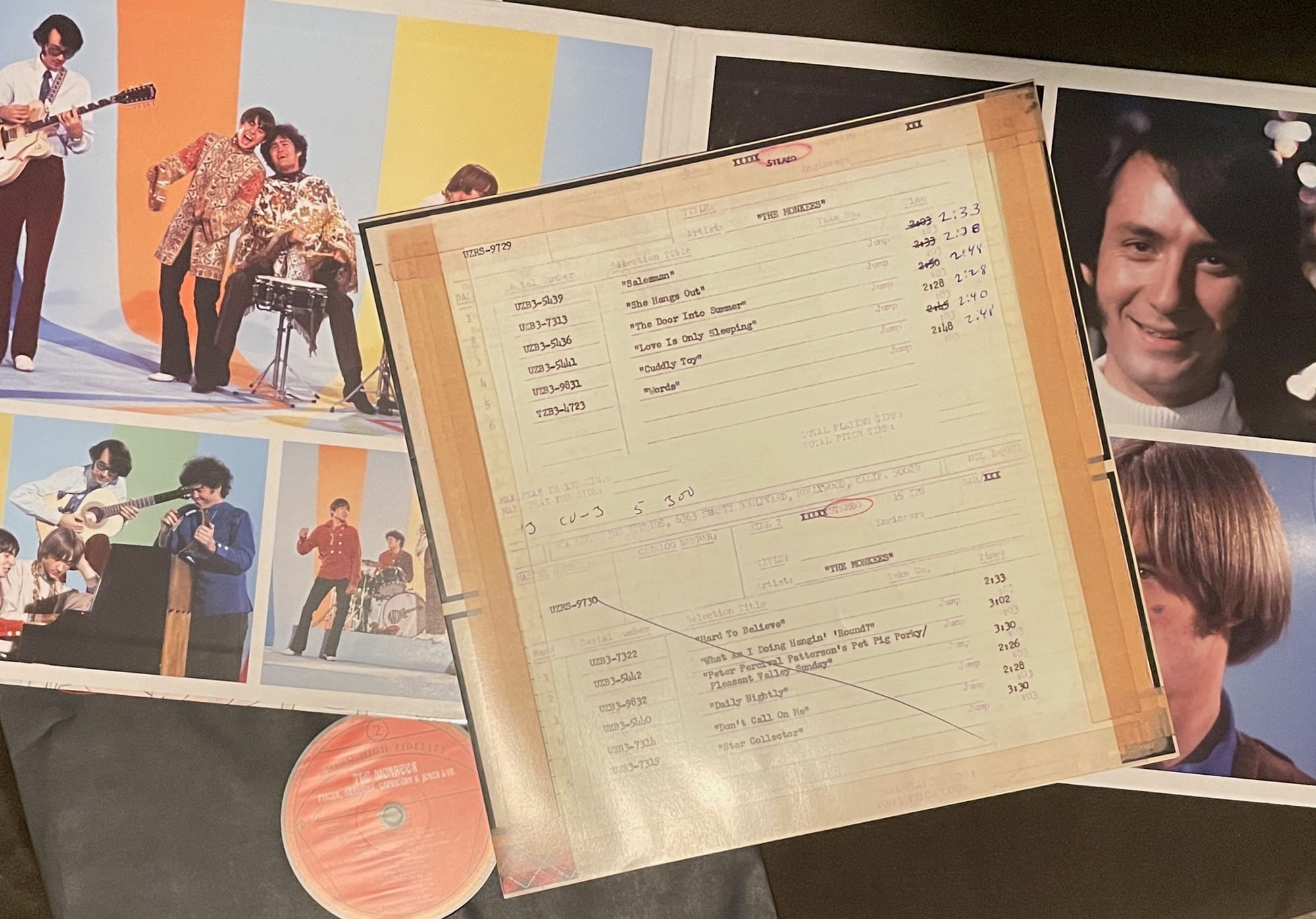

But what makes Pisces absolutely ideal for RHF is this: As revealed in this new pressing’s liner notes—by longtime Monkee historian Andrew Sandoval—the original stereo master tape for Pisces has never been pressed to vinyl before. Originally released on Colgems and pressed by RCA, those millions of copies of Pisces that sold ’round the world were all cut from third-generation copy tapes. So if Rhino is going to give Pisces its first vinyl rendition cut directly from the master, why not do it at the highest level?

Those copy tapes of Pisces—the Monkees’ third album of 1967 and their fourth overall—were EQ’d and compressed to be in line with RCA Records’ cutting guidelines, Sandoval says. What that means isn’t exactly clear. Were they trying to make these discs sound smaller and junkier so that they could be safely played on little kiddies’ portable record players? Probably not, actually. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, RCA manufactured some of the very best stereo records in the US, but in 1963 they adopted the Dynagroove treatment, which introduced subtle distortion to the signal as a bizarre means of combatting the distortion inherently produced by cheaper consumer players. (It wasn’t a very good idea.) Until around 1970, Dynagroove was implemented on everything RCA released, from their finest classical recordings to their crudest pop slabs, so whatever they needed the Pisces master tape to do was probably something in line with those requirements.

Happily, the new Rhino High Fidelity version of Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd. was cut directly from the original analog master by Kevin Gray of Cohearant Audio without any of that interference. And it sounds phenomenal. It’s the best I’ve heard the stereo version sound on vinyl, by a long shot. (I imagine the original mono version also used copy tapes—maybe we’ll get an all-analog version of that someday.) I compared the new RHF to a 1968 RCA Indianapolis press with 5S/5S stampers, and the difference was night and day. I also had a 1986 Rhino pressing handy, but since that uses a few alternate mixes, it wasn’t an entirely useful point of comparison. (Full disclosure: I have not heard the 1996 Sundazed cut, nor the Rhino cut from the 2016 Classic Album Collection box set, which was later released in 2022 as a stand-alone. Friday Music’s mono version from their 2014 mono box set and its stand-alone release from 2021 were also not useful points of comparison, as they don’t use the stereo mix.)

And here’s the real reason why it makes sense for Rhino High Fidelity to do a pressing of Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.: It’s a terrific album. It’s easily the Monkees’ best long-player (Head has some equally great moments but simply doesn’t have all that much music on it). Recorded after the artistic breakthrough of Headquarters—in which the four Monkees played on all the songs as opposed to having studio musicians do most of the work—Pisces finds the band locating a happy medium between outside contributions and their own creative ideas. And it was recorded, in part, while the Monkees were touring, meaning that Mike Nesmith, Micky Dolenz, Peter Tork, and Davy Jones were existing as a band rather than as TV co-stars, playing music together daily and more or less getting along. Significantly, Nesmith dominates, especially in the vocal department. Previously relegated to two or three songs per album, he was always the Monkees’ strongest songwriter and performer, and his increased presence on Pisces kicks the album up a level.

What’s more, Pisces was the first Monkees album to be recorded after the seismic wave that was Sgt. Pepper, and it contains large dollops of the psychedelia and studio trickery that had become very much in vogue. It was a good fit for the Monkees and their bassist/producer Chip Douglas (formerly of the Turtles). Grafted on to their California brand of pop—which already bore traces of country, Tin Pan Alley, and a slightly more polished version of good ol’-fashioned American garage rock—the extra-musical elements made the catchiness weirder and the weirdness catchier. The most obviously psychedelic moments are the Moog synth freakouts on “Daily Nightly” and “Star Collector” (played by Dolenz and Paul Beaver, respectively), but there are little bits of lysergic pixie dust in every nook of Pisces.

For example, there’s the hard cutoff at the end of “Cuddly Toy” where Jones and Dolenz’s voices become a mirror shattered into a thousand pieces. There’s the wraithlike echo during the chorus of “Words,” punctuating Dolenz’s melody like a ghostly shriek from another room. There’s the locust-like chitter that accompanies the circular 7/4 guitar riff during the opening of “Love Is Only Sleeping.” And there’s the conclusion of album highlight “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” where all the voices and instruments turn into a giant smear—its summertime suburban diorama morphing into something much more subversive.

Lyrically, too, the album falls back on certain themes that reflected the changing times, particularly the sexual revolution and the conservative hand-wringing that accompanied it. “She Hangs Out,” “Cuddly Toy,” and “Star Collector” are all lightly sexist condemnations of young women who go too far. (In a pinch, “What Am I Doing Hangin’ ’Round” could fit in that category, too.) “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” of course, condemns—or does it celebrate?—the conformity of American suburban life, with the sound of a teenage garage band’s rehearsal as part of the backdrop. “Daily Nightly” is a surreal deconstruction of nightlife on the Sunset Strip, illustrated by Nesmith in abstract, trippy metaphors, and “Salesman” is most flagrant of all, depicting a dealer plying his wares and “sailing so high.”

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Monkees album without a bit of razzle dazzle, and that’s best embodied by “Hard to Believe,” a Jones collaboration with the Sundowners’ Kim Capli, who played all the instruments—bar horns and strings—by overdubbing himself on a new-at-the-time eight-track recorder. Nesmith, too, embraces his showbiz side with the loungey “Don’t Call on Me,” to which the band added audio-verité sounds of a fake nightclub. And the album’s most regrettable misstep, Tork’s spoken-word “Peter Percival Patterson’s Pet Pig Porky,” is a 30-second vaudeville joke that gets more and more irritating upon repeat listens. The kids probably loved it back in the day, though.

The album’s twin masterpieces, and they are towering, are the aforementioned “Pleasant Valley Sunday” and the simultaneously energetic and sumptuous “The Door into Summer,” a gorgeous, nostalgic sunbeam of a song with wonderful playing and indelible Monkees harmonies. In fact, the four never sang together better than on Pisces—“Pleasant Valley Sunday” is the only Monkees song with lead vocal roles for Dolenz, Nesmith, and Jones within its interlocking countermelodies, and Dolenz and Tork circle each other like prizefighters during the verses of “Words.”

All of this sounds fabulous in Gray’s cut. His work has sometimes been characterized as being overly bright, and while I don’t think that’s the case here, no one will accuse this version of Pisces of being dark. But the accented treble, to the extent there is any, suits the album, which was never designed to have a thumping bottom end. Even Douglas’s bass is there primarily to serve a melodic role.

And Gray’s renowned strength—of fully revealing what’s on the tape—pays off handsomely here. The steadily building arrangement of “The Door into Summer” becomes positively ecstatic, particularly when the second drum kit kicks in in the left channel. Doug Dillard’s electric banjo in “What Am I Doing Hangin’ ’Round?” is jaw-dropping, offering tiny little grace notes and bends that never had a chance to be noticed on the RCA pressing; here, they’re rendered in breathtaking detail. And “Hard to Believe,” probably the album’s worst song, might just be its best-sounding recording. The separation of each instrument is remarkable, with Capli’s elaborate percussion overdubs rendered in crystal-clear imagery, Jones’s voice sounding stunningly realistic, and the track’s over-the-top arrangement never quite tipping into aural incoherence. (Are those tubular bells? I never noticed them before!)

There are a couple of blips, likely due to the source tape. The high, stabbing piano during the chorus of “The Door into Summer” has always sounded distorted, and it does here, too. There’s also some distortion during the final seconds of “Pleasant Valley Sunday.” Additionally, when Dolenz sings “with a kiss to seal it” during the second verse of “Words,” there’s some undeniable sibilance. And this may just be a personal thing, but the newly rendered clarity of “She Hangs Out” steals away some of the murk that made that song bounce a certain way; here, it sounds cleaner—I’d never realized how deliberately lascivious Jones is trying to sound—but it just doesn’t quite tickle my ears the same.

The pressing, done at Optimal, resulted in an essentially flawless copy in my case, perfectly flat and blemish free. The Stoughton gatefold sleeve is of the typical high quality we’ve come to expect from the RHF series. (Is the disc difficult to get back into the overly stiff jacket? Yes. Is the spine needlessly thick, taking up far too much shelf space? Yes. Does the front cover look absolutely amazing once you take the obi off? Yes.) Sandoval’s liner notes, interestingly, include track-by-track credits along with the technical notes, as opposed to a longer essay that could have provided a narrative of where the Monkees were during the second half of 1967.

The transparency of the audio, though, is the real story here. This isn’t the best-sounding recording 1967 has to offer, to be sure, and its technical limitations are made all the more evident through this fully revealing rendition. But when you think of all the inventiveness that Pisces contains, from the swirling brilliance of “Pleasant Valley Sunday” to the genuinely deranged climax of “Star Collector,” sending the album into outer space for its final throes, being able to hear it with this much precision and clarity draws you exponentially closer to the music. This doesn’t sound like a teenybopper record from nearly 60 years ago. Rather, this new cut reveals Pisces to be an ambitious, exploratory, and boundlessly creative pop album made in the wake of the Summer of Love, when everything didn’t just seem possible, it very nearly was.

Rhino High Fidelity 1-LP 33 RPM • all-analog lacquer cut from the original master tape by Kevin Gray of Cohearant Audio • pressed at Optimal • black vinyl, numbered edition of 5000

Listening equipment

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980