Rhino Rocktober: Fleetwood Mac, Mr. Bungle, Warren Zevon, Ministry, and Jethro Tull

Vinyl reviews of Fleetwood Mac’s Bare Trees; Mr. Bungle’s Disco Volante and California; Warren Zevon’s Mr. Bad Example, Learning to Flinch, and Mutineer; Ministry’s The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste and Psalm 69; and Jethro Tull’s Minstrel in the Gallery. Whew.

More months need to have names that can be gently tweaked so that they include references to musical genres. Right now we just have October/Rocktober.

Maybe we could we get Funkuary? Metalvember? Jazzy July? Are you listening, record labels?

Because right now Rhino Records is eating your lunch, depositing a veritable onslaught of vinyl reissues on unsuspecting record buyers this month. In fact, Rhino has 43 reissues coming out over the course of Octobe—excuse me, Rocktober. If only every month could be this jam-packed.

Our Rocktober series continues today—if you missed our first Rocktober post, we reviewed reissues by the Doors, Yes, and Morphine. Be sure to check it out here.

And no less than 15 Rhino reissues are coming to record stores today, Friday, October 24, 2025. Let's see what Rocktober looks like this week:

• Dream Theater: Six Degrees of Inner Turbulence [clear vinyl]

• Dream Theater: Train of Thought [clear vinyl]

• Dream Theater: Octavarium [clear vinyl]

• Dream Theater: Systematic Chaos [clear vinyl]

• Fleetwood Mac: Bare Trees [Rhino Reserve]

• Jethro Tull: Minstrel in the Gallery [50th anniversary edition - Steven Wilson remix on marbled vinyl]

• Ministry: The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste [expanded Edition]

• Ministry: Psalm 69 [expanded Edition]

• Mr. Bungle: Mr. Bungle [translucent orange crush vinyl]

• Mr. Bungle: Disco Volante [translucent light blue vinyl]

• Mr. Bungle: California [translucent ruby vinyl]

• Stone Temple Pilots: Stone Temple Pilots [red vinyl]

• Warren Zevon: Mr. Bad Example

• Warren Zevon: Learning to Flinch (Live)

• Warren Zevon: Mutineer

We’ve got reviews of no less than NINE of these reissues right here for you now, and good news—none of them are for Dream Theater! (Just kidding, we respect and appreciate Dream Theater and their very sophisticated, technical musicianship. We just don’t want to have to write about it.)

Here’s what we did review:

Fleetwood Mac: Bare Trees [Rhino Reserve]

Mr. Bungle: Disco Volante and California

Warren Zevon: Mr. Bad Example, Learning to Flinch, and Mutineer

Ministry: The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste and Psalm 69 [expanded editions]

Jethro Tull: Minstrel in the Gallery [Steven Wilson remix]

Read on to see which new reissues are worth your money, time, and potential hearing loss. And we’ll be back next Friday with our final Rocktober installment, so be sure to subscribe to The Vinyl Cut if you haven’t already.

Fleetwood Mac: Bare Trees [Rhino Reserve]

Review by Ned Lannamann

The gulf of Fleetwood Mac albums that came between 1970 and 1974 is a fascinating, voluminous trove. This was a band in continual, tumultuous evolution, struggling to find a consistent identity but acquiring and shedding its contributors on an almost annual basis. (A fake “New Fleetwood Mac” even hit the road for a brief stretch.) This lost period—coming after their 1969 masterpiece Then Play On and before they turned into superstars with 1975’s Fleetwood Mac and 1977’s Rumours—resulted in a string of albums that are wildly inconsistent and never fully satisfying. With one exception, none of the six albums feature the same lineup that appeared on the previous album.

That exception is 1972’s Bare Trees, and while it’s a little tough to definitively say it’s the best of the albums that came between the Peter Green era and the Buckingham/Nicks years, it’s certainly in the running. This was a Danny Kirwan album more than it was a Christine McVie or Bob Welch album, who each contributed two songs to Kirwan’s five. But what it really signifies is a settling-in, a level of comfort and continuity that came after the growing pains of 1971’s Future Games, their first album after founding member Jeremy Spencer’s sudden departure.

That’s a long way of saying Bare Trees doesn’t sound a whole lot like what most people think of as Fleetwood Mac, even despite the familiar presence of Christine McVie. And any resemblance it has to the Peter Green era comes entirely from Kirwan, the immensely talented songwriter/guitarist/vocalist who joined the group as a teenager and eventually found himself at the artistic reins. Kirwan’s lovely, delicate songs served as sort of sorbet-course cleansers between Then Play On’s bigger moments; here, they’re the main course. And Kirwan rises to the challenge, with the high-energy rockers “Child of Mine” and “Bare Trees,” the swooning instrumental “Sunny Side of Heaven,” and the elegiac “Dust,” which is a damn heavy song for a 21-year-old to have written. In it, Kirwan seems to be reflecting on the end of the ’60s and the casualties Fleetwood Mac lost along the way, and simultaneously predicting his own flame-out that would soon precipitate his departure from the band a few months after Bare Trees’ release.

Kirwan’s helped by Welch and Christine McVie, both of whom contribute the best songs they ever wrote: “Sentimental Lady” by Welch, who later had a solo hit with it, and “Spare Me a Little of Your Love” by McVie, a song that comprehensively charts the soft-rock landscape of tender feelings she would explore, with great success, throughout the ’70s and ’80s. There’s also an audio-verité recording of one Mrs. Scarrott, an elderly neighbor of the band who recites one of her poems to conclude the album on a somewhat bizarre note.

And so Bare Trees remains an odd duck, with individual moments that are very good and yet never fully cohering as an album. It’s well performed and generally well recorded (at De Lane Lea’s ill-fated location in Wembley), although apparently the original album master tape was demagnetized when the band ran it through an X-ray machine at a New York airport. The band had to hastily reconstruct the mix in a short period of time at the Record Plant, and that may be why the finished product is slightly murky and dense, although this also was very much the style of 1972 British rock in general.

Rhino Reserve’s new pressing of Bare Trees puts it in its very best light. Cut directly from analog tape by Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab in Salina, Kansas, the dense soup of the master is never fully clarified, but the instruments are given new transparency that is not present on the earlier pressing of the album that I compared it to. (That older copy, pressed at Capitol’s Los Angeles plant and without an identifiable mastering credit, dates from some time in the late ’70s, likely pressed up quick-like in the wake of Rumours’ massive success.)

The biggest difference is Mick Fleetwood’s kick drum, which really cuts through on the new Rhino pressing, generating a physically felt thump that moves through the room. While fully audible on my older cut, it never acquires the Reserve’s level of tangibility. The bottom end—coming from both John McVie’s bass and, to a surprising degree, Christine McVie’s keyboards—is similarly well defined as a whole, adding a presence that roots the album to the ground, whereas the older cut seems to float, unanchored, a couple of feet from the floor. Inversely, I also noticed that the highest crash cymbal sounds on the older cut broke up and fell apart, whereas Lutthans’ version keeps them intact.

Still, there is an overarching thick, woolly quality that seems to be inherent to the recording itself, whether it came from the rushed mix job in New York or whether it traveled across the Atlantic already baked into the multitracks. That slight muddiness keeps the otherwise illuminating Rhino Reserve pressing from attaining showroom status, although there is a gently liquid quality to the music that my ears really enjoy.

The Rhino Reserve package is high-quality but barebones, with no additional material, liners, photos, or anything, save for the hype sticker that needs to be torn in half in order to access the album. The wonderfully moody original cover, featuring a frame around the photo of leafless trees in mist, is here (the frame was removed for later pressings, for some reason), and the jacket has a matte finish that gestures toward but doesn’t replicate the original’s textured sleeve. Manufactured at MoFi’s Fidelity plant in California, my pressing was awfully good, with maybe a tick and click here or there, and a slight visual inconsistency in the black vinyl that did not affect the sound. Considering every other pressing I’ve gotten from the Reserve series has been essentially flawless, I’m not too messed about it.

One last thought: As I mentioned, Lutthans’ cut comes from the analog master in Rhino’s possession, but with all albums of British origin, there is always a question of whether the US “master” tape is a copy or indeed the original. Record companies have always been loose with the term “master.” And with Bare Trees having been mixed in New York City—and considering that the band eventually relocated from the UK to California (did they bring their masters with them?)—the pedigree becomes even more complicated. Without being able to see a photo of the tape box, and lacking more precise information from Rhino, the question remains, at least in my mind. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely to me that the sound could have been measurably bettered. If ever a pressing of Bare Trees could win over fans unfamiliar with the pre-Buckingham/Nicks years, this new Rhino Reserve is probably the one to do it.

Bare Trees | Rhino Reserve 1-LP 33 RPM • all-analog lacquer cut from master tape by Matthew Lutthans of the Mastering Lab • pressed at Fidelity • black vinyl

Listening equipment

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980

Mr. Bungle: Disco Volante; California

Review by Robert Ham

Like all good cult bands, Mr. Bungle has attracted a fan base that is dedicated and opinionated. There are multiple online forums where supporters debate the finer points of setlists, lineups and, yes, the quality of the vinyl pressings of the group’s studio output to date.

So much so that when Rhino announced this year’s batch of Rocktober releases, which includes new editions of the three LPs that Mr. Bungle recorded for Warner Brothers—1991’s John Zorn-produced self-titled album, 1995’s Disco Volante, and 1999’s California—the takes began flying almost immediately. (A representative comment from the band’s subreddit: “Kinda wish the California/bungle logo was more in the center like the original rather than at the top but that’s just a nit pick.”) You can imagine, then, the tone of the commentary about these colored vinyl Rocktober editions when it was revealed that the reissues were pressed from the same lacquers Scott Hull cut at Masterdisk for Quote Unquote 1991–1999, the 2024 box set that contained all of the above Bungle LPs.

Let me explain: When they were initially issued on vinyl in the ’90s, all three albums were single-disc pressings, squeezing a lot of music (in the case of Mr. Bungle, a full 70 minutes of audio) onto two sides of a record. The 2024 pressings were all double LP sets, wisely giving this complex and, at times, heavy art rock some room to breathe.

It also gave Hull a little more space to play with. So, on Disco Voltante, he and Rhino tacked on both “Platypus,” a proggy jam originally issued on a bonus 7-inch that came with the 1995 pressings, and “Mind Emissions,” a solo piece by master percussionist William Winant recorded during the album sessions, while opting to not to include the track “Spy” (or “Secret Song,” as it was sometimes known), which was “hidden” as a concentric groove next to “Carry Stress in the Jaw” on the first vinyl version. The band revisited that tune during the sessions for their follow-up, but it stayed in the vaults until it was added to the end of California when it was pressed for Quote Unquote, bearing the new title “Gnosterces.” When those changes were discovered by the Mr. Bungle purists, a small ripple of discontent followed. As one poster on the Steve Hoffman Music Forums bluntly put it, “Apparently they left ‘Secret Song’ out of Disco Volante! That is un-fckng-forgiveable. Also shoehorned a couple semi-useless bonus tracks into the albums. Best best [sic] is still original pressings or the Music on Vinyl pressings, I’d wager.”

While I can’t attest to what the MoV editions have to offer, I can speak to how this new pressing of Disco Volante sounds in comparison to an OG. Mastered by Bernie Grundman and pressed at Specialty Products, the 1995 version sounds cramped and dulled, what with a full 34 minutes of music shoehorned into each side of the LP. The remaster by Hull, pressed on lovely baby-blue translucent wax, brings the bite back to this album. Each of the many twists and turns these songs make feel clearer than ever, with distinct highs and gut-churning lows. I did detect a bit of noise in the margins of “Desert Search for Techno Allah,” but that was the one glaring anomaly in an otherwise clean, flat pressing. And wouldn’t you know it, “Mind Emissions” works great in the track sequence, taking the baton of “Carry Stress” with a perfectly executed drum fill before heading into a delirious and circuitous audio history lesson on 20th-century percussion music.

California sounds even better. Some of the credit is due to the more straightforward approach the band took to songwriting this time around. It is, without question, Mr. Bungle’s most accessible album. The ’50s R&B pastiches “Vanity Fair” and “Pink Cigarette” are cut from the same sackcloth as David Lynch’s extended musical universe, and for all of its squiggly noise and lyrics of technological disaster, “The Holy Filament” is the closest thing to a ballad this band ever produced. Still, the new pressing on translucent red wax puts all of this and more in razor-sharp focus. I liken it to zooming into a segment of a Jackson Pollock action painting. Even amid the slight bits of noise that creep into the first disc of this set, the shades of each instrument and every last squeal, gurgle, and croon that emanates from vocalist Mike Patton’s throat has an almost overwhelming amount of detail and color.

Disco Volante | Rhino 2-LP 33 RPM • mastered from unknown source by Scott Hull • lacquer cut by Hull at Masterdisk • plated at GZ Media, Czech • pressed at GZ’s Memphis Record Pressing • translucent blue vinyl

California | Rhino 2-LP 33 RPM • mastered from unknown source by Scott Hull • lacquer cut by Hull at Masterdisk • plated at GZ Media, Czech • pressed at GZ’s Memphis Record Pressing • translucent red vinyl

Listening equipment

Table: Cambridge Audio Alva ST

Cart: Audio-Technica VAT-VM95E

Amp: Sansui 9090

Speakers: Electro Voice TS8-2

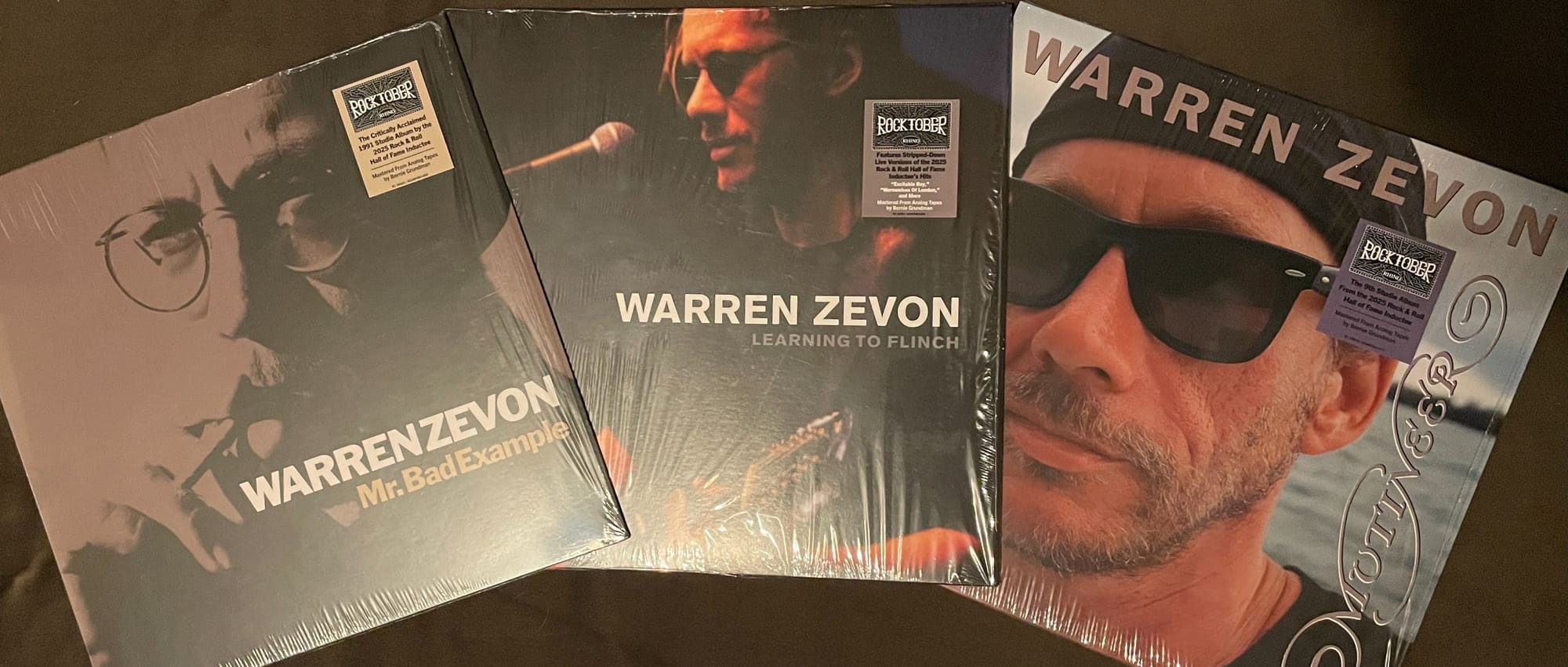

Warren Zevon: Mr. Bad Example; Learning to Flinch; Mutineer

Review by Ned Lannamann

On Record Store Day earlier this year, Rhino issued Piano Fighter, a 4-LP box set that collected the three albums Warren Zevon recorded for Giant Records in the first half of the ’90s: 1991’s Mr. Bad Example, 1993’s solo live album Learning to Flinch, and 1995’s home-recorded Mutineer. Those marked the first-ever vinyl releases for two out of the three; Mr. Bad Example had one vinyl run in Germany upon its original release. Now for Rocktober, Rhino is selling them as three separate vinyl albums (Learning to Flinch being a double LP), allowing the less casual Zevon devotee, if there is such a thing, to pick them up one by one. This period found Zevon in a quote-unquote “mature” phase of his career, albeit one that saw him coming down off some indie-cred shine earned by 1990’s Hindu Love Gods, the collaborative album of shambolic blues covers he recorded with members of R.E.M.

Mr. Bad Example is a fully loaded, well-produced singer/songwriter record circa the early ’90s, for better or worse. That means it possesses a slick, corporate feel that’s at odds with Zevon’s acerbic songwriting—although in my opinion this is also the case with his best-known work, 1978’s Excitable Boy. Maybe, in fact, that is the crux of Zevon’s oeuvre (apologies for using the words “crux” and “oeuvre” so close together): the juxtaposition of his literary, occasionally nasty songs against a competent, overly polished backdrop, played by ace studio musicians with smooth-as-silk backing vocals from ultrafamous guest stars.

Learning to Flinch is altogether more revelatory, collecting a career’s worth of his best songs, played in solo live performances from his 1992 tour. Zevon the songwriter has nothing to hide behind, with a 12-string acoustic guitar and some keyboards his only accompaniment. The album is not the best-sounding document, with Zevon’s voice often mixed too low and his amplified acoustic guitar bearing a somewhat brittle and dated sound. But it feels honest in a way his studio stuff doesn’t.

Which makes Mutineer a bit ironic. Consisting of home recordings of Zevon on his own (with a few guests here and there), he tries to emulate a larger-sounding production rather than achieve a stripped-down sound that would allow his songs to cut to the bone. His musicianship notwithstanding—he acquits himself well in all regards, from good-enough-sounding electronic drums to some ripping lead guitar—there’s a dated sound to the recording that can’t be avoided. Hidden behind overdubbed synths and overdriven guitar, the intimacy of the Zevon we heard on Learning to Flinch is obscured. And yet, his peerless songwriting pokes through, seemingly chafing at its somewhat chintzy trappings.

The pressings are very similar to what appeared in the Piano Fighter box set, as this set uses the same plates cut by Bernie Grundman. The Piano Fighter discs were pressed at Record Industry in the Netherlands, while these new represses bear the mark of GZ’s Memphis Record Pressing. Per the hype stickers, all three albums were mastered “from analog tapes,” but the liner notes for Learning to Flinch says it was recorded direct to DAT, and the home-recorded source for Mutineer has me thinking it’s pretty likely that it was tracked on a digital workstation. Of course, they all could have been transferred to an analog reel for their final mixes, but I’m just asking questions here. At any rate, they sound excellent—better than digital sources have up ’til now.

My Memphis pressings had a couple garden-variety issues, in the form of an unfortunate repeating tick that marked up a section of Side 1 of Mr. Bad Example and another that persisted through “Werewolves of London” on the live set. But they were flat and free of marks, and the packages are more than adequate, featuring polylined sleeves and inserts that include complete lyrics. The information from the eight-page booklet that came with the Piano Fighter box is not reproduced, sadly, but otherwise, these are strong, straightforward presentations that allow the strengths of these slightly thorny albums to shine.

Mr. Bad Example | Rhino 1-LP 33 RPM • lacquer cut by Bernie Grundman • pressed at Memphis Record Pressing • black vinyl

Learning to Flinch | Rhino 2-LP 33 RPM • lacquer cut by Bernie Grundman • pressed at Memphis Record Pressing • black vinyl

Mutineer | Rhino 1-LP 33 RPM • lacquer cut by Bernie Grundman • pressed at Memphis Record Pressing • black vinyl

Listening equipment

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980

Ministry: The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste; Psalm 69 (expanded editions)

Review by Robert Ham

Last Rocktober, Rhino graced us with deluxe reissues of Twitch and The Land of Rape and Honey, the two albums that found Chicago industrial band Ministry moving as quickly beyond the synthpop sound of their earliest work as their junk-sick legs could take them. This year, the reissue label continues the thread with new pressings of Ministry’s next two studio forays: 1989’s The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste and 1992’s ΚΕΦΑΛΗΞΘ, the album better known as Psalm 69.

At the time these two albums were conceived and recorded, alternative, as a genre, was on the ascendent, with major labels starting to pick off the juiciest artists from a variety of local scenes. Ministry already had a leg up in that department thanks to their ongoing deal with Sire Records and a blistering live show that united goths, punks, and metalheads into a teeming whole. With the wind in their sails and some of Seymour Stein’s money in their collective bank account, the ensemble, led by musician/producers Al Jourgenson and Paul Barker, upped the intensity and volume of their attack by roping in the likes of Mike Sciacca and Louis Svitek, both veterans of the late ’80s heavy rock scene, and incorporating the tempos of speed and thrash metal into their already hard-driving assault.

Though these albums share the same constituent elements, the albums are entirely different animals. Ministry still carried some of the sonic signifiers of the European industrial and darkwave bands that influenced them on Mind: the bleating analog synths, the danceable tempos, and the copious use of a sampler. Nearly all of that went by the wayside with Psalm, where they opted for a pummelling approach that maintained a sense of humor (the transcendently over-the-top “Jesus Built My Hotrod”) among tunes like “TV II” and the title track, which might as well have been recorded with power drills and jackhammers.

These reissues attempt to tell the most complete story behind the genesis and fallout of these records as they can in the space Rhino allowed, which to be fair was generous. First pressings of Mind and the multiple reissues of the album squeezed 50 minutes of music onto a single disc. This new edition spans three sides of a double-LP set, all the better to let the power chords and tribal rhythms of tracks like “Faith Collapsing” and “So What” achieve their maximum walloping effect. This also left them room to add in “Dream Song,” a track previously only available on the CD and cassette versions of the album, and, on side four, three tunes released on the “Burning Inside” single.

There’s even more bonus material included with Psalm. As the original album clocked in at a comfortable 44 minutes, the second disc of this set is taken up with the remixes and B-sides found originally on the three singles Sire plucked from the album at the time. (The edit of “Just One Fix,” featuring spoken word from Beat poet William S. Burroughs, is a particularly nice inclusion.) For all that, Psalm is the poorer sounding of the two reissues. Likely due to the group tracking those sessions with a computer, the music doesn’t hit the jugular as hard as it otherwise might have. A bump in volume helps make up for some of what's lacking, but it still comes off as paltry when compared to the sound of Mind. Even though I suspect that a digital step was involved in the mastering—details on that and the pressing of these reissues are scarce—there’s a noticeable leap in attack when it comes to the older album. Barker’s bass and the drumming of the late Bill Rieflin comes to the fore with some additional muscle behind them, and there’s a layer of crunchiness to the midrange that hits the eardrums with a decisive force. The digital origins of Psalm, meanwhile, leaves a tinny sibilance that affects Rieflin’s cymbals and other tones in the higher registers that becomes more acute and wearying, especially on Side Two of the main album. Overall, it’s a marked improvement over the squinched sound of the original double 10-inch version that Sire issued in 1992, but still missing some of the sonic overload that this music deserves.

The Mind Is a Terrible Thing to Taste | Rhino 2-LP 33 RPM • mastered from unknown source • lacquer cut by Henry Rudkins of AIR Studios • pressed at GZ Media, Czech • black vinyl

Psalm 69 | Rhino 2-LP 33 RPM • mastered from unknown source • lacquer cut by Henry Rudkins of AIR Studios • pressed at GZ Media, Czech • black vinyl

Listening equipment

Table: Cambridge Audio Alva ST

Cart: Audio-Technica VAT-VM95E

Amp: Sansui 9090

Speakers: Electro Voice TS8-2

Jethro Tull: Minstrel in the Gallery (Steven Wilson remix)

Review by Ned Lannamann

It’s a little hilarious that Jethro Tull recorded their eighth album in Monte Carlo, of all places. When you think of their British-as-hell, classically tinged prog-folk-rock, you don’t really think of casinos, Mediterranean sun, and ostentatious wealth, but that’s where 1975’s Minstrel in the Gallery went down. Ian Anderson apparently hated being in Monte Carlo, which isn’t surprising, although he was also going through a divorce at the time. The rest of the band seemed to have a nice enough time.

The album betrays no evidence of being shot on location in one of the ritziest places in the world. It contains a song called “Cold Wind to Valhalla,” for crying out loud. Minstrel is—and I mean this as a high compliment—a damp, dour, hirsute, vaguely medieval tromp through the array of familiarly gloomy moods that Jethro Tull explored so successfully on 1971’s Aqualung and 1972’s Thick as a Brick. The band was recovering from the severe critical backlash from 1973’s A Passion Play and 1974’s War Child, and Minstrel managed to find them making really exciting music again, particularly the title track and the lengthy “Baker St. Muse” suite, which rank among the band’s best moments, highlighted by guitarist Martin Barre’s searing contributions.

Already available overseas, the 50th anniversary vinyl edition of Minstrel in the Gallery debuts in American stores this week as part of Rhino’s Rocktober. Manufactured by Warner’s Parlophone imprint (and featuring a reproduction of the original Chrysalis label, although Chrysalis these days is a separate independent label not connected to Warner), it comes on translucent gray marbled vinyl featuring Steven Wilson’s excellent remix that was originally part of the album’s 40th anniversary box set. A single-disc version of the remix was released on vinyl in 2015, and this is essentially a repress of that, with one very important difference: The 2015 vinyl edition included a 24-page booklet with extensive liner notes, recording information, photos, and more. This one? Nothing. Nada. There’s not even a reproduction of the lyric inner sleeve that came with the original 1975 pressing. You slice open the shrinkwrap and inside the jacket is just: a record. (In a polylined sleeve, mind you, but still.) Quite a poor showing in that regard, I have to say.

The Wilson remix really brings the album to life, though, and its appearance on vinyl is not guaranteed to last—the 2015 pressing is already commanding steep prices on Discogs. By all accounts, Wilson’s remixing approach has done wonders for the Tull catalog; something about his taste and technique really uncovers a lot from their original multitracks. In my opinion, Wilson is not the remix savior some have cast him as, and he hasn’t done nearly as wonderful a job with certain albums as he has done with the Tull stuff, but this Minstrel remix puts Tull and Wilson in their best light. My theory is that it has to do with the highly theatrical, almost comically dynamic qualities of Tull’s music, in which they will go from whimsical medieval balladry to crushingly heavy rock, sometimes within the span of a few bars, as Anderson’s impish troubadour persona merrily Morris-dances atop it all. That’s the sort of exaggerated, high-drama frivolity that can really shine in a fresh and sparkly remix.

This new pressing, using the same plates as the 2015 edition, easily conveys the full dynamics of Wilson’s high-resolution digital master. I can’t see evidence of a lacquer cutting engineer in the deadwax, so my assumption is that it was done in-house at the Optimal pressing plant in Germany, where both the 2015 and the new version were pressed, but the specific party responsible must remain a mystery unless more info is out there. The gray marbled vinyl generally sounds excellent but not flawless: I encountered a repeating tick during the first minute or so of the album (especially irritating during the hushed opening dialogue), and a few other flecks of sound that did not disappear after an ultrasonic cleaning. As always, I would have preferred a sensible, straight black repress—multicolored vinyl never completely works, in my opinion—and I definitely would have preferred that they include the booklet. But for a quick, easy way to commemorate the half-century mark of an overlooked gem in a major band’s catalog, this repress of Minstrel in the Gallery will have to do. If you lost track of Tull at Aqualung, this is the best possible place to pick up the thread.

Minstrel in the Gallery | Parlophone 1-LP 33 RPM • unknown lacquer cut from digital source • pressed at Optimal Media GmbH • translucent marbled gray vinyl

Listening equipment

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980