The Real Hero of 'Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere': The Cutting Lathe

Greetings, young (and not so young) vinyl lovers. We’ve got a lovely new edition of the newsletter for you today, but first...

Congratulations to Allan, the winner of this month’s vinyl giveaway! He’ll soon be receiving the test pressings of the recently released Definitive Sound Series one-steps of R.E.M.’s Chronic Town and Murmur. Spin them in good health, Allan!

Want to get lucky like that? Consider upgrading your subscription. We’re doing monthly giveaways, but the only way to enter is by being a paid subscriber. Click below to get that rolling.

Today, we are getting back to part of our original vision for this newsletter. While reviewing vinyl reissues is our primary focus, we also want to include some more editorial-type work, like my piece on record shopping in Reykjavik or my interview with Zev Feldman about his new imprint Time Traveler Recordings.

We also wanted to welcome new voices into the mix, which we are doing for the first time this week. The following piece was written by Jason Wojciechowski, a gent who is part of the team behind Object Permanence, a new vinyl pressing plant that will be up and running in Salem, Oregon, very soon. (We’ll have more on that at The Vinyl Cut in the very near future.)

The 2025 biopic Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere tracks the period of Bruce Springsteen’s career that resulted in the album Nebraska, and with the movie arriving on Hulu this month, the timing couldn’t be better to enjoy Jason’s look at how a key part of that film is the creation of the first vinyl copies of that spare, haunting 1982 LP.

The Real Star of Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere: The Cutting Lathe

by Jason Wojciechowski

The trip to see Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere was part of an annual tradition of my mom and me watching that year’s big music biopic. The film zooms in on the short period where the Boss wrote and recorded the songs for his sixth album, Nebraska. We were quiet leaving the theater. In the car she pronounced her verdict: “Well, that was depressing.” This isn’t an unauthorized version, but the story Springsteen, who was on set most days, wanted to tell. A strange and brave choice.

Nebraska is Springsteen at the height of disconnection—from his band, his community, the commercial expectations of stardom, even from himself. After touring The River, he sequestered himself in a rented house in Colts Neck, New Jersey, in December 1981. In the film he consumes a diet of dark murder movies, Flannery O’Connor stories, and grainy flashbacks to confrontations with his alcoholic father, all while recording demos on a four-track TEAC 144 Portastudio. The tape was meant as source material for fuller versions of the songs he’d record with the E Street Band.

Director Scott Cooper gives the audience two scenes of reprieve from Springsteen’s spiraling depression. One is the electric moment when the band plays the iconic full-throated version of “Born in the U.S.A.” for the first time at New York’s Power Station studio. Goosebumps. The other is a romantic montage set to “I’m on Fire.” We catch a glimpse of the far more palatable movie that could have been made, but that is all we get. Like the album, the film was panned for being too honest. Killian Faith-Kelly’s critique of the film in GQ pronounced, “Spareness does not equal subtlety,” and “Something being true doesn’t make it interesting.” Another critic called it “a bleak downer”—actually, that was the Washington Post’s Richard Harrington reviewing Nebraska in 1982.

Springsteen removed the certain chart-toppers “Born in the U.S.A.,” “I’m on Fire,” and “Glory Days” from the album, saving them for his 1984 release. He jettisoned his band and instructed manager Jon Landau and producer Chuck Plotkin to transfer the demo tape directly to lacquer. The pivotal scene sees Springsteen chastising the mastering engineers for trying to make his album sound better.

“I don’t wanna make it better, Jon,” he tells his team. “I just want to get back to what happened in the bedroom. That’s it.”

He wanted no place to hide the failings—not the hiss, not the distortion, not the loneliness, not the darkness. The emotional rawness of Nebraska’s songs demanded sonic rawness to match. Any polish would be a lie.

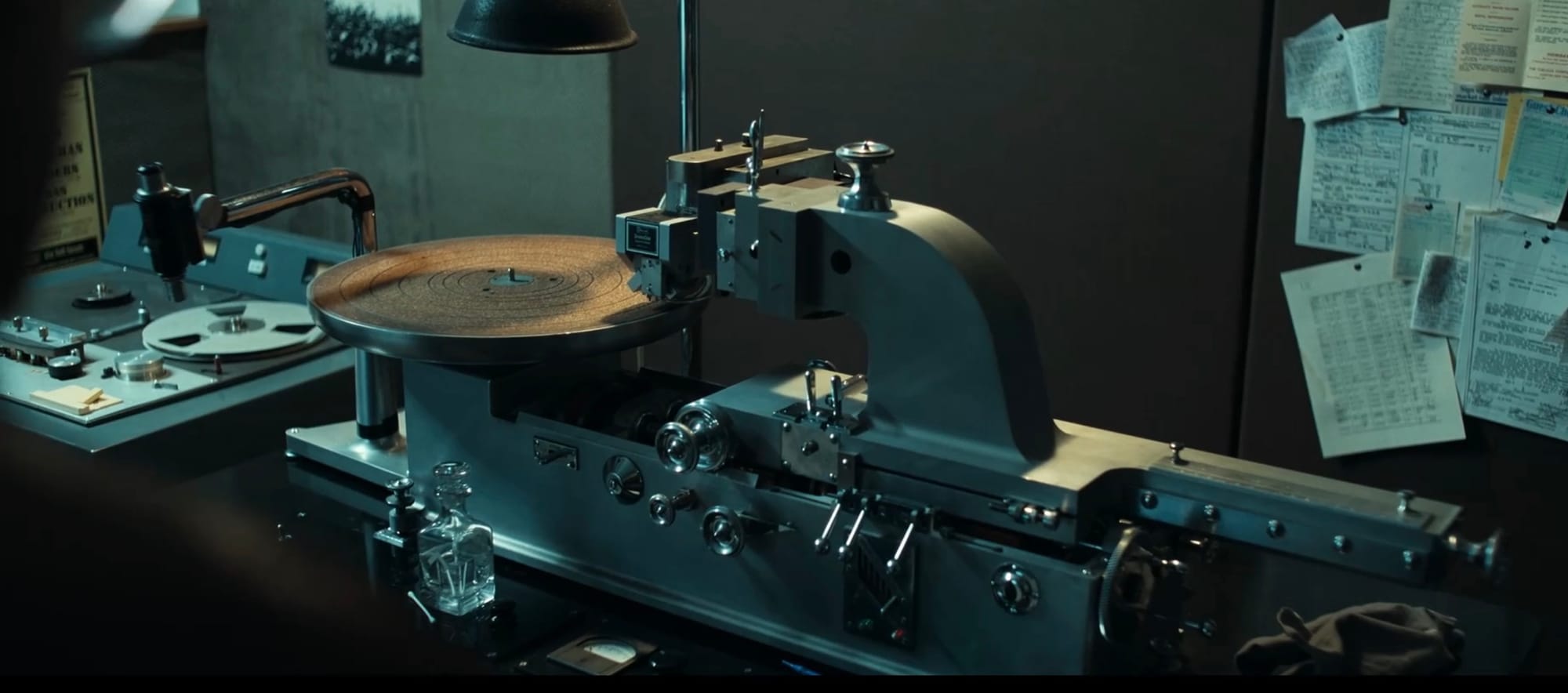

Enter the real star of the movie: the cutting lathe.

It’s rare that the manufacturing process, or something as obscure as the lathe used to cut a record, makes it into a Hollywood movie. Days after my trip to the theater, I traveled to Nashville for Chris and Yoli Mara’s annual Vinyl Bootcamp at Welcome to 1979. I had questions about that lathe. Fortunately, the assembled mastering engineers were all on the super-secret cutters group chat, where their colleague had just shared that it was his lathe featured in the movie. My next stop happened to be Brooklyn, where mastering engineer Paul Gold works.

Salt Mastering in Greenpoint feels like stepping into 1982. Even the new equipment, like the custom Shaker A/B console that Gold built over the span of 15 years, looks like machinery from the analog era. His Neumann VMS66 lathe was used for the cutting scenes, along with a Scully 601 that the production bought and shipped from the UK. Production designer Stefania Cella saw the potential of the space immediately, as did the director, who decided to shoot extra scenes in Gold’s studio. On December 20, 2024, actors Marc Maron and Christopher Jaymes spent the day pretending to cut the record with Gold’s extensive help.

For the uninitiated: Records start with music mastered to a lacquer—a 14‑inch aluminum disc coated with soft lacquer into which a cutting stylus made of diamond or sapphire carves a spiral groove mirroring the original sound waves. The lacquer is metalized and submerged in a nickel bath until you get stampers with ridges instead of grooves that mold hot PVC into thousands of identical copies.

Jaymes’s character explains the tortured process for this particular cut that required half a dozen attempts on different lathes: “I’ll have to adjust the depth and the distance between the grooves by hand… the old way, and cut it at an incredibly low level so the needle doesn’t dig too deeply into the vinyl.” The mono master lacquer was ultimately cut with the oldest lathe they could find, a Scully lathe first manufactured in 1950.

“Most people would think that, since it’s just a guitar and voice, it would be easy to cut,” Gold explains. “And that is completely the opposite of reality.” The cassette had “very quick changes in level, jumpy levels.” He demonstrates by speaking normally and suddenly LOUDLY. “It’s very hard for the needle to trace that.”

The sparse instrumentation compounded the problem. “If you have a full band together, there are a lot of places you can hide the distortion,” Gold notes. “With a guitar and voice, there’s no place to hide the bad things.”

Our brains are wired to recognize when a human voice or acoustic guitar sounds wrong. Distortion becomes impossible to mask. Which is exactly what Springsteen wanted. The technical challenge mirrored the emotional one: How do you preserve brutal honesty? How do you transfer raw vulnerability without losing what makes it true? By keeping the gaps, refusing to compress and combine.

The craftspeople who manufacture a record work against physics to imprison time—a sound already slipped into the past. In 1982, legendary mastering engineer Bob Ludwig worked with Atlantic’s Head of Mastering Dennis King on multiple lathes to freeze a moment that was already gone the instant Springsteen lifted his fingers from the guitar strings.

The high point of Deliver Me from Nowhere isn’t an energetic concert scene, but Springsteen listening to the cut with satisfaction. His manager says, “We got it. The echo; the emotional atmosphere; every imperfection.” The price of bottling that moment is that Springsteen won’t tour the album, appear on the cover, or give a single interview.

Landau later wondered if Springsteen was trying to delay what was surely to come—the fame, leaving his New Jersey community behind. Everyone in his orbit was prepared for him to progress on the same timeline toward superstardom. But Springsteen found his own proper time. He wanted to hold onto that sound in that bedroom, that connection to the place and life slipping away.

On his song for New Jersey on the album,“Atlantic City,” Springsteen sings, “Everything dies, baby, that’s a fact.” He’s singing about America dying during the 1980s recession, rough edges being smoothed away as Atlantic City tries to clean up its dark underbelly, and himself—a present version of the Boss quickly receding into the past. Everyone who worked on the album created a record that is explicitly an analogue—a copy that admits it’s a copy. We might not connect with it the first time, but that’s why records are so magical… there’s always another trip around. Maybe on the fifth or 500th spin, we’ll merge timelines and get it. Or maybe we never will, which is okay. Time is funny and we never know where these crisscrossing timelines will lead.