Review: Fleetwood Mac in 1971

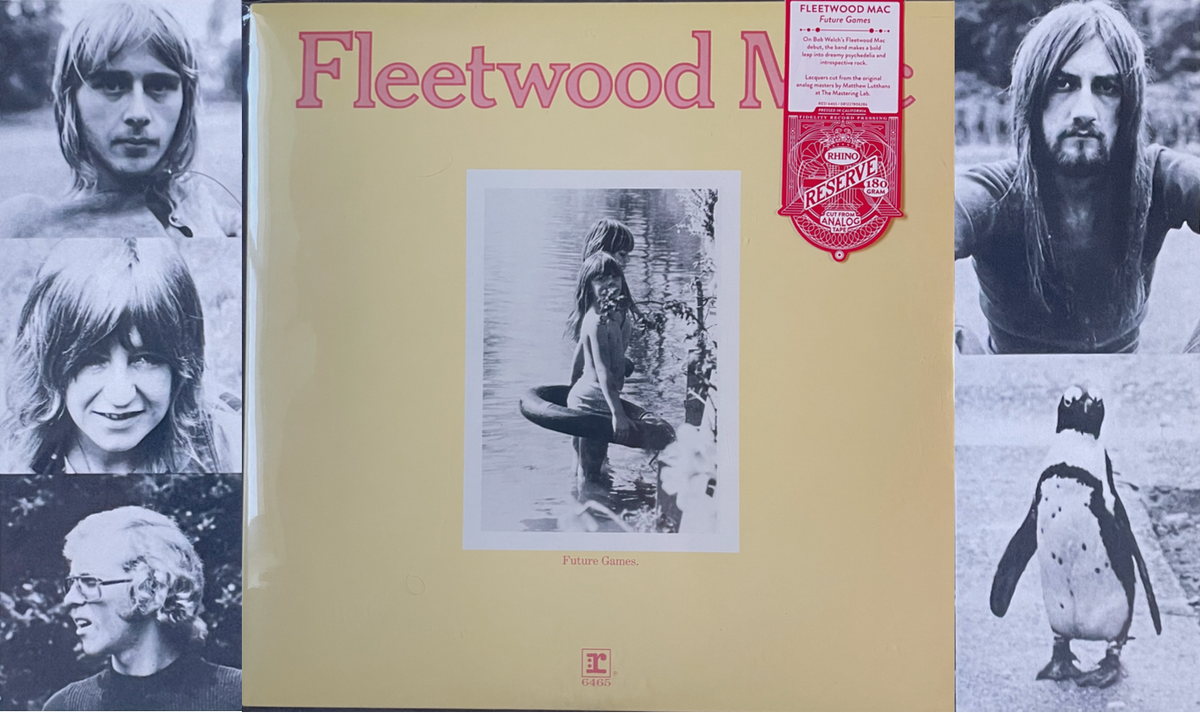

The Rhino Reserve series continues apace with a definitive edition of Future Games.

Not even a year old, the Rhino Reserve series has quickly become one of the most appealing and reliable vinyl reissue lines around. The formula is stupidly simple: Take a slightly less well-known album from the vast Warner catalog, bring the master tapes to a top-notch cutting engineer in a world-class facility, and press ’em darn-near perfect every time. Charge customers a mild but not exorbitant premium—there are no Stoughton tip-on jackets here to pad the price tag—and keep everything in print as much as possible. (Right now only three Rhino Reserves are marked as “sold out” on Rhino’s site, with another, Curtis Mayfield’s Curtis, not currently listed, as it was a Record Store Day Black Friday exclusive, although we hope it sees a proper wide re-release soon.) At this point the criteria for a Rhino Reserve release is getting a little muddy, as the selections are feeling less and less like they’re coming from the “overlooked gems” bin. But the consistency in the quality of the product hasn’t flagged an iota.

Rhino has released eight new Reserve titles this January so far, with a ninth (Tower of Power’s Back to Oakland) on the way before month’s end. These have all been hitting brick-and-mortar stores as part of the Start Your Ear Off Right campaign, with direct-to-consumer sales turning up on the Rhino site shortly thereafter. We’ve reviewed four of the January Reserves so far, and we’re aiming to have reviews for all nine in the next couple of weeks. There are also some choice Reserves coming the first week in February—four wonderful soul and R&B records, harkening back to the soul and funk albums the series launched with last January—but let’s not get ahead of ourselves just yet. (Those February releases are Donny Hathaway’s Live, Otis Redding’s Pain in My Heart and The Soul Album, and Sam and Dave’s Hold On, I’m Comin’, all due out February 6.)

Today we continue our January Rhino Reserve overview with a lesser-known work from one of the Warner catalog’s mightiest thoroughbreds: the long-lived, shape-shifting Fleetwood Mac.

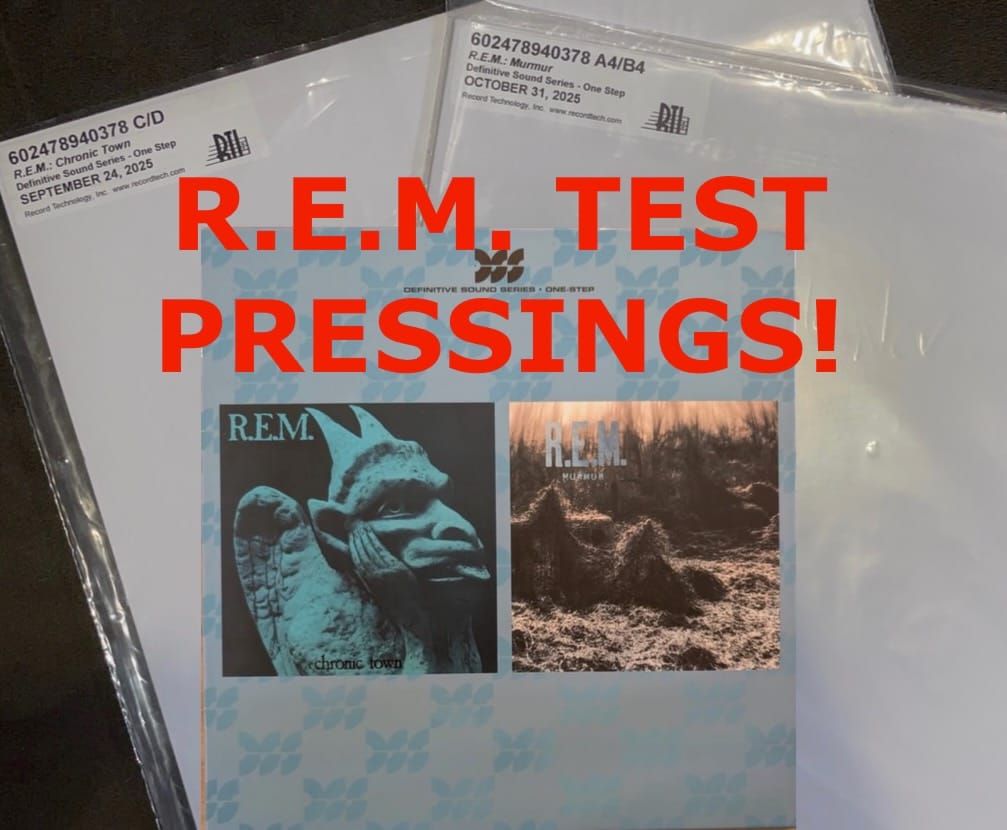

But first, a quick reminder about our January vinyl giveaway. We’re giving away test pressings of the amazing Definitive Sound Series one-step pressings of R.E.M.’s Chronic Town EP and Murmur LP. This is a great way to hear one of the most talked-about vinyl reissues of 2025—for free! And these test pressings are likely to become collector fodder in years to come (this statement should not be construed as financial advice and may not be used for investment purposes).

Head over here for the lowdown on how to win—and how to upgrade to our paid subscriber tier, which is just a really nice place for you to be.

And now, on to today’s review.

Fleetwood Mac: Future Games

Mapping out the pre-Buckingham/Nicks years of Fleetwood Mac is a rock cartographer’s dream, not to mention a record collector’s. The band, formed in 1967 after evolving out of another band, John Mayall’s Blues Breakers, would acquire and lose members with virtually every album for its first eight years, meaning that Fleetwood Mac’s first nine studio albums bear little consistency with one another, let alone with the West Coast folk-rock-pop that would become their calling card in the mid-’70s. And with non-album singles, live records, and outtakes collections littering the spaces in between those first LPs, an obsessed fan could spend a lifetime attempting to get definitive vinyl versions of all their early recordings. (Some assuredly have.)

For all but diehard collectors, one corner on the Fleetwood Mac map is now a lot easier to chart. In October, Rhino Reserve released an excellent new mastering of 1972’s Bare Trees—we’ve got a review of it here—and now they’ve dropped its closest cousin in the band’s discography, 1971’s Future Games, in a similarly first-rate edition. These two albums are among the only early Fleetwood Mac albums to have a consistent lineup on consecutive releases, featuring the newly acquired Christine McVie and Bob Welch alongside guitarist Danny Kirwan and the band’s two constants, drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie.

Future Games is a mellow affair, not exactly pointing the way forward to the Rumours-era soft-rock hit machine but also quite a ways from the band’s bluesy beginnings. The band is in hippie-commune mode, with a liquescent, mutable sound that bears the hangover of “Albatross,” the dreamily trippy instrumental that gave the band a number-one UK hit in January 1969. There are a few forthright rockers on Future Games, but the band seems less interested in pursuing volume than in inhabiting a more contemplative, jasmine-scented sound.

The album was the group’s first with Christine McVie (née Perfect) as a full-fledged member. She had contributed to 1969’s Then Play On and 1970’s Kiln House—her backing vocals on “Station Man” are readily identifiable—and she officially joined the band on the latter album’s tour, adding keys, vocals, and her formidable songwriting chops. Future Games is also the first album with guitarist Bob Welch, who was brought on board to replace founding member Jeremy Spencer. Spencer had abruptly abandoned the band before a February 1971 gig in LA, joining the Children of God religious cult; his absence also meant that his love for rock ’n’ roll pastiches no longer needed to be part of the band’s sound. In that way, Future Games sounds like a deliberate move away from Kiln House, where Spencer’s retro shtick took over large chunks of the LP.

Spencer was the second founding guitarist the band had lost to a psychological break, as former bandleader Peter Green had just departed the previous year following a bad acid trip. All of that turmoil may have resulted in some seriously jangled nerves on the remaining members’ parts, and Future Games finds the band drifting and in search of an identity. The songwriting is split between Kirwan, Christine McVie, and Welch, with the slight edge going to Kirwan, who had joined the band as a teenager just three years before, and now—in the absence of Green and Spencer—had become its de facto artistic leader through process of elimination. Kirwan would gain confidence on the following year’s Bare Trees, but here he seems relatively tentative and unsure of himself, turning in three decent if slightly wispy tracks. Perhaps he had retrenched after one of his more promising songs, “Dragonfly,” had not done particularly well when it was released as a non-album single earlier in the year.

The opening track, Kirwan’s gossamer, acoustic-strummed “Woman of a Thousand Years” pivots straight to Christine McVie’s uptempo churner “Morning Rain,” allowing Fleetwood Mac to play both sides of the ballad/rocker fence. That interesting tension is lost with the instrumental jam “What a Shame,” which, despite augmentation on sax from Christine’s brother John Perfect, feels like an unfinished backing track (which it more or less was—it was hastily added to the album when the label refused to release it with only seven songs). It’s up to Welch’s lengthy title track to provide a centerpiece, which slowly builds up a sense of mystic mystery over its eight minutes. “Future Games” shows why the capable Welch was brought on board: The song has an inherent appeal but not a ton of personality, allowing the band to graft itself onto it and transform it into something with gravity. From Kirwan’s seagull-swooping guitar arpeggios to Christine’s cathedral organ, Fleetwood Mac almost achieves the beauty of Green-era triumphs like “Man of the World.”

Kirwan’s “Sands of Time” kicks off Side 2 and similarly strives for a crystalline beauty, although despite its genial sound it becomes a bit static over its seven minutes, feeling like a lengthy preamble to a payoff that doesn’t come. “Sometimes,” another one by Kirwan, is a country-tinged jaunt that veers into slightly heavier territory, presaging Welch’s “Lay It All Down,” which capitalizes on a wiry guitar riff for a quickly galloping, R&B-tinged rocker; the arrangement, however, remains a bit leaden when the song needs to be fleet of foot. Christine McVie’s “Show Me a Smile” ends the album on a gentle note, a calming song addressed to a young child.

The album’s production strives for lushness rather than precision or power—it was recorded at the state-of-the-art Advision Studios in London, which had one of the only 16-track tape machines in London at the time, and the band may have taken advantage of its capabilities to excessively thicken their sound. The Rhino Reserve edition’s mastering, by Matthew Lutthans of the Mastering Lab, achieves that perfect balance of being forceful and yet easy on the ears. All the instruments, from Fleetwood’s low-tuned snare drum to Welch’s and Kirwan’s intertwined guitars, are depicted with warmth and richness, and the music sound-image contains a stirring amount of dimensionality, as the different instruments and voices almost seem to form shapes in front of the listener. (Note: Lutthans’s initials in the deadwax are accompanied by “ACV,” referring to Amos Vegas of Acoustic Sounds, who lent his expertise and familiarity with the album during the mastering process.)

I have an older copy of Future Games to compare the new one to, but it’s not a fair fight. My old copy is a Columbia House record club pressing of indeterminate age, and while it’s enjoyable enough when taken on its own terms, it’s downright dismal compared to Lutthans’s work. The more layered sections become gluey, and the brighter-sounding parts become brittle. At other times, the sonic image becomes diffuse—the colors are still vibrant, but it’s like an image going slightly out of focus. On Lutthans’s cut, that doesn’t happen even for an instant. The bass is anchored yet expressive, and the guitars shimmer in golden and silver hues. The upper mids are rendered in full detail but never with excessive brightness, and the overall package is balanced and clear, with plenty of horsepower.

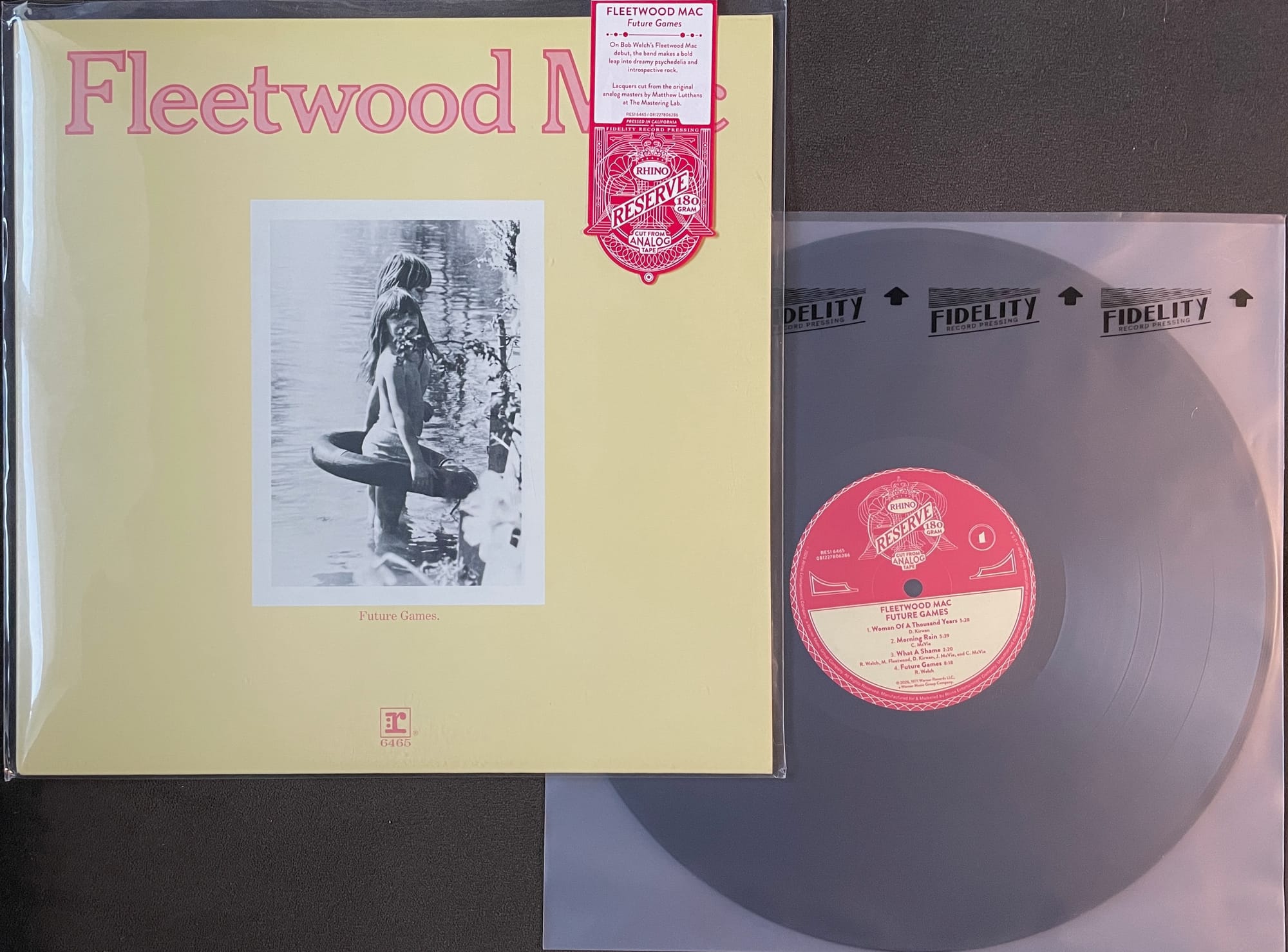

I would like to hear an original UK pressing of Future Games, since this was recorded in the UK and the first pressings were cut by George “Porky” Peckham, one of the most renowned cutting engineers of all time. It also may be one of the only cuts from the original master tape—it stands to reason, to me, that Rhino is using Reprise’s US copy tape for this Reserve pressing, although the state and location of Fleetwood Mac’s UK master tapes is something I don’t have any knowledge of, so I’m happy to be proven wrong there. I noticed that the very end of the fadeout of “Morning Rain” is cut off on this new cut, something that’s not present on other copies of Future Games I’ve heard. The pressing, like virtually every Rhino Reserve, is close to flawless, although I did detect a tiny introduction of noise in the very last grooves on each side, something I’ve noticed on other recent Reserves as well. Otherwise, the pressing—from Mobile Fidelity’s Fidelity Record Pressing—is flat, centered, and with virtually silent backgrounds. It’s a beautiful piece of vinyl. The jacket is yellow, per the first pressings, and not the green that appeared on later editions.

Future Games finds Fleetwood Mac at an unusual juncture. Freed of Jeremy Spencer’s Sun Records fixation, the band can’t quite conjure up the boisterous, infectious qualities of “Station Man,” the decided highlight from Kiln House. But they were capable of falling back on weaving the beautiful tapestries of sound that characterized past successes like “Albatross” and “Man of the World”—even if at this particular point, their songwriting did not match their capabilities as arrangers and performers. Kirwan, Welch, and Christine McVie would sharpen up noticeably on 1972’s Bare Trees, a better album even as it’s a more uneven one. But what they deliver here sounds very pleasant and lush indeed, with a verdant, overgrown sound that continually draws the ear in even as the mind wanders. With this superb new Rhino Reserve cut, the tangled overgrowth of Future Games is that much more irresistible.

Rhino Reserve 1-LP 33 RPM 180g black vinyl

• New all-analog remaster of Fleetwood Mac’s 1971 album

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single pocket

• Inner sleeve: Fidelity Record Pressing–branded poly

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: None

• Source: Analog; “Lacquers cut from the original analog masters”

• Mastering credit: Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, Salina, KS

• Lacquer cut by: Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, Salina, KS, with assistance from Amos Vega; “MCL/ACV” in the deadwax

• Pressed at: Fidelity Record Pressing, Oxnard, CA

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A- (slight rustling at the very end of each side)

• Additional notes: Comes inside reusable poly sleeve sealed by hype sticker, as per other Rhino Reserve titles.

Listening equipment:

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980