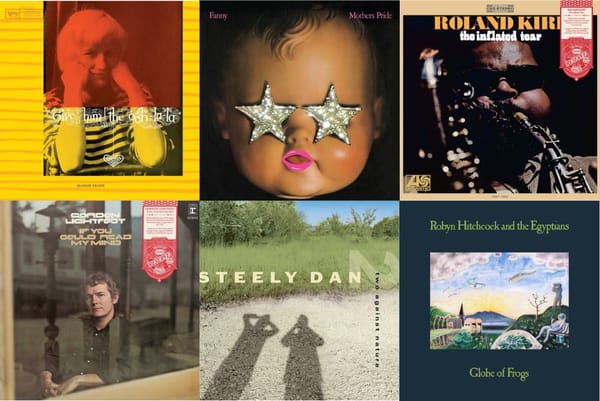

Review: Funkadelic's first album is back on wax—twice!

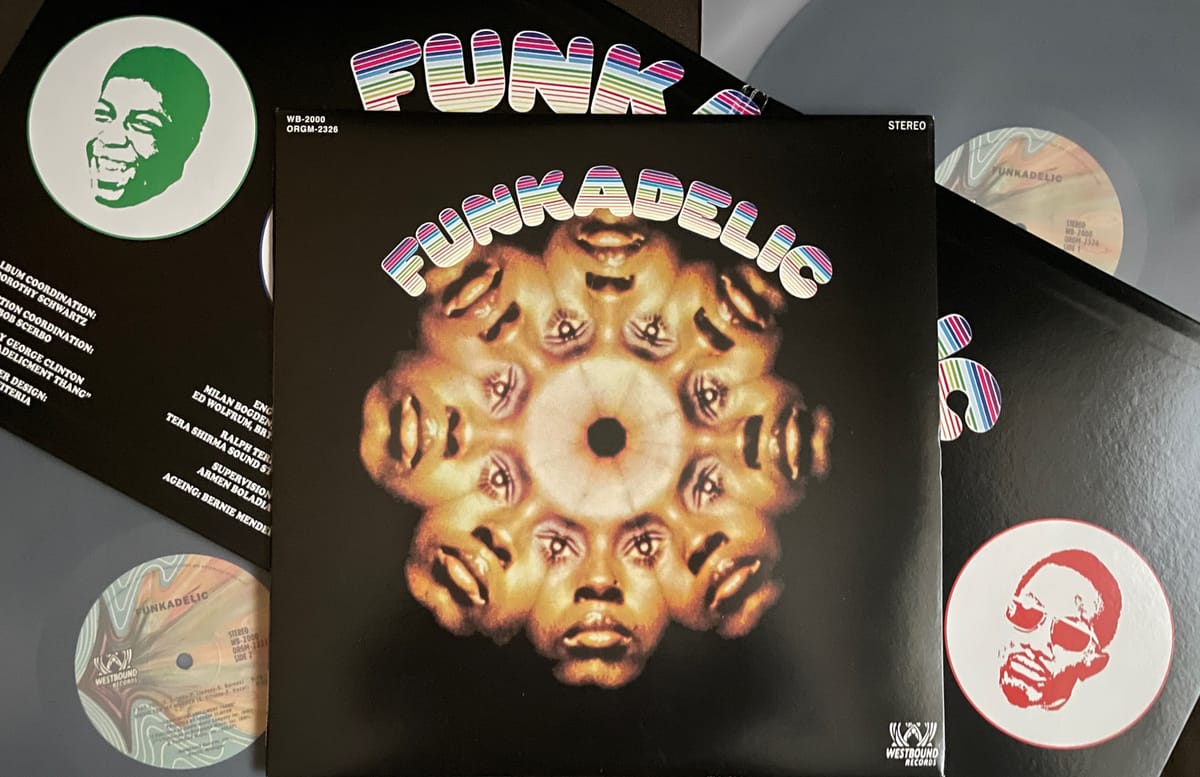

Org Music has released 1970's Funkadelic in 33 and 45 RPM versions. We listened to both.

When news broke in 2023 that Org Music would be reissuing the Westbound catalog on vinyl, the first thing that crossed most people's minds was, "Cool, when's the Funkadelic coming?" That legendary Detroit band, led by George Clinton—and one-half the Parliament-Funkadelic collective that directed the trajectory of American funk through the 1970s—has had a checkered history on vinyl, especially their 1971 classic Maggot Brain, one of the most coveted albums for record collectors and one that has been particularly ill-served by shoddy represses.

Two years on, the Org/Westbound campaign is fully under way, with several fabulous reissues of stuff by the Counts, Denise LaSalle, Ohio Players, Assemblage, and more on vinyl and digital formats. And now, here it is: Org's first Funkadelic re-release, a multi-format revisiting of their self-titled 1970 debut—itself a tricksy, shapeshifting album that arrived at the midway point between the psychedelic hangover of the 1960s and the powder-fueled bump-and-grind of the 1970s. While much of the Funkadelic LP is more groove-oriented than song-focused, it springs to new life in Org's versions, clarifying that this is not just the formal full-length introduction of a remarkable figure in American music (one Mr. George Clinton) but also an exceptional document of an extremely tight, extremely loose band: guitarists Eddie Hazel and Tawl Ross, drummer Tiki Fulwood, and bassist Bill Nelson (keyboardists Mickey Atkins, Bernie Worrell, and Earl Van Dyke also make contributions), with Clinton twisting the dials to turn it into something wildly hallucinogenic.

I should probably break down what exactly Org has done with Funkadelic, at least in terms of vinyl. (Buckle up—it's a bit complicated.) There are two vinyl versions to choose from: a 33 RPM single disc that was cut from a newly created high-resolution digital file of the original master, and a 2-LP 45 RPM version that was cut from a newly created analog copy of the original master. The creation of both the digital and analog copies was necessary due to the condition of the master tape, according to tape archivist and restorer Catherine Vericolli, who published a fascinating, detailed, and thoughtful overview of the process on Org's site that you should definitely read. Dave Gardner of DSG Mastering worked side by side with Vericolli, performed the mastering of both analog and digital versions, and cut the vinyl with assistance from Phillip Rodriguez. You can read his take on the process in an Instagram post. The collaboration between Gardner and Vericolli was somewhat unique, in that a mastering engineer and a restorer/archivist were working in tandem, but such was the historic importance of the project.

This post on the Steve Hoffman Music Forums includes an additional quote from Gardner that further clarifies why the single-disc 33 RPM version was cut from digital. Essentially, Side 1 of Funkadelic tops out at nearly 25 minutes and would have to be severely compromised in order to be cut from tape. Digital tools, however, could allow it to retain near-to-full dynamic range (I'm assuming via the use of delays and perhaps a tool that could automate the ability to cut the grooves closer together during quieter stretches?) as well as a super-wide stereo image, necessary for an album where the stereo image is shifting nearly every second. I'll go a little further into the technical side later on, but for now let me say that these two versions provide a wealth of comparison points that are pretty fascinating.

And I'll stop burying the lede here: We've got a 33 RPM digital cut going head-to-head with a 45 RPM analog cut—simultaneously tackling vinyl nerds' two main points of contention in one fell swoop. Digital vs. analog? 33 vs. 45? Could these Funkadelic reissues settle these everlasting debates once and for all? Spoiler: No, not quite. It's more complicated than that (it's always more complicated than that). But I was shocked at what I personally responded to when listening to these two versions. Not because the result itself was shocking, necessarily, but because how definitively clear-cut it was for me and my ears.

The sounds on the discs themselves are astonishingly dense, with instruments gliding in and out of the picture, ghostly overdubs shimmering continually, and a spaceship fleet's worth of echo, effects, panning, and feedback to turn it all into delirious cosmic soup. Hazel, Ross, Fulwood, and Nelson provide the backbones here, often in the form of loose-limbed jams that are equal parts Hendrix, the Meters, and Sly and the Family Stone. Clinton acts as ringmaster, providing occasional vocals, bringing in guests like the Parliaments on "I Bet You" and Dennis Coffey on "Mommy, What's a Funkadelic?" and turning every dial behind the board so that these basic R&B grooves transform into something magmatic and foreboding. The guitars of Hazel and Ross are the star attraction, but the rhythm section of Fulwood and Nelson is just as crucial.

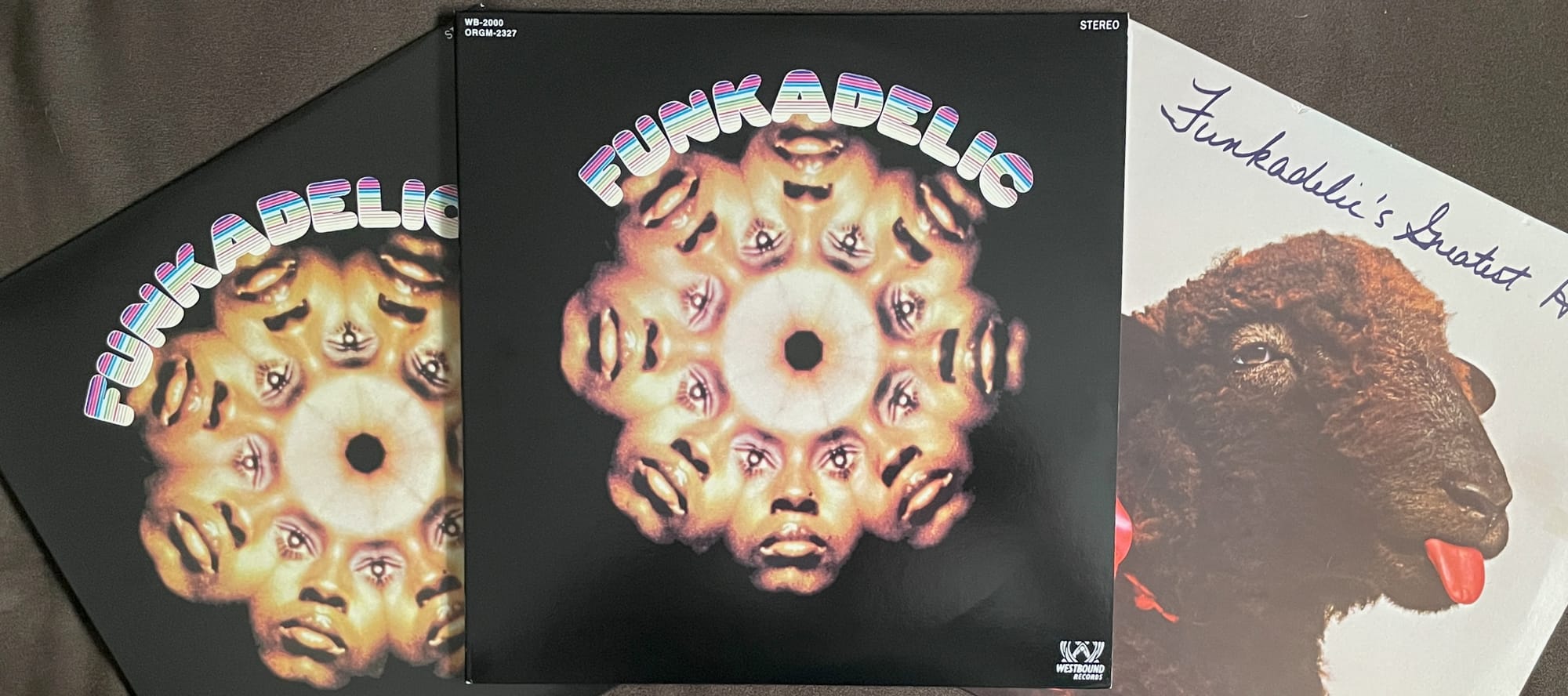

What became clear to me—with both of these new versions—is that it's time for this album's reputation for having low fidelity to be obliterated. This is a rich, lustrous recording, as lush as it is disorienting, and both the 33 and 45 are able to extract a juiciness on the master tapes that probably hasn't been heard until now. (That album-opening lick—a literal lick—never sounded so wet.) While I do not have an original copy Funkadelic to compare these new cuts with, I have been referring to my 1975 Westbound pressing of Funkadelic's Greatest Hits to give me some sense of what these might have sounded like back in the day. The two Funkadelic songs included on Greatest Hits are "I Got a Thing, You Got a Thing, Everybody's Got a Thing" and "I Bet You"—(down) strokes of luck, because "I Got a Thing" is the most sonically and rhythmically dense track on Funkadelic and "I Bet You" has the most infectious groove, reliant on air and bounce to get its feeling across.

Whatever the provenance of my 1975 Greatest Hits pressing may be (it appears to have been pressed at GRT Pressing, but I can't tell much more than that), it suffered tragically in comparison to these two new Org cuts. On the '75 Greatest Hits, "I Got a Thing" was pitiful, almost illegible—the production sounded so jumbled and clattering that I occasionally had trouble telling where the downbeat was. "I'll Bet You" fared better but still felt constrained, with a smaller soundscape that was rougher on the years, especially during the high, piercing feedback sounds that coruscate throughout the song. Fulwood's spontaneous live-room drum sound, so exciting on the Org discs, came off as puny and lo-fi here.

So it's possible that the new Org versions are better than what a lot of people heard in the '70s. (There is also a 1989 vinyl pressing of Funkadelic that I haven't heard but is well regarded.) But the real question at hand is: Which new cut's better, the digital 33 or the analog 45? During my listening—which is totally subjective and wholly dependent on my equipment, biases, and taste—I found the analog 45 cut to be deeper, fuller, and more pleasurable in every regard. One of the things I love is when a sonic image seems three-dimensional to me, and perhaps that's an aural illusion, but I got that sensation throughout the entirety of the analog 45. I also experienced a few instances of synesthesia and even got goosebumps once or twice. What makes Funkadelic such a cool listen is that it features very natural, organic band sounds butting up against a purely artificial, studio-concocted psychedelic overlay. And the analog 45 made that juxtaposition sound perfectly correct, not leaning too far in one direction or the other.

Some other highlights from the 45: Nelson's solo on "Mommy, What's a Funkadelic?" is perfectly anchored, sounding as full as I've ever heard an electric bass sound on a rock or soul record—you can hear each motion of his fingers on the strings. The scream in "I Bet You" leading into Hazel's guitar solo is just pure hair-on-fire excitement; if this doesn't do it for you, nothing will. During the instrumental breakdown in "Good Old Music," it feels like Tiki Fulwood has set up his drum kit just behind the speaker line... actually, that's not quite right. It doesn't feel like he's visiting you—it feels like you've teleported into the studio to visit him, and you can hear the space and sound of the live room by how the bass drum echoes off of it. And the way "Qualify and Satisfy" evolves from a standard blues stomp into a psychedelic suite is as full of drama and intrigue as any tightly paced thriller; the lucidity of the analog 45 cut makes each plot twist easy to follow.

The digital 33 has a lot to recommend it, of course. It's cheaper, and you don't have to get up to flip the sides so often. But I actually found that breaking up the repetition of Funkadelic worked in its favor. Some of the jams and rhythms can run into each other; with the analog 45, I always knew where I was within the album. Look, the digital 33 sounds damn good. It will probably make most people happy. But it just didn't have that last little sparkle, that bit of fairy breath that made the analog 45 sound so magical to me. I should also say that my copy of the digital 33 seemed to suffer from a few pressing defects, including bits of noise throughout the disc and a sharp, quick stab of crunch that sounded like a symptom of non-fill to me. Maybe that made it easier to love the analog 45. But I was surprised how emotional my response was. Analytically, it might have been tough for me to pinpoint the differences by trying to rely on rationalizations about transients and low end and presence—but the truth is, I just felt happier listening to the 45. At the end of the day, I think that's all I can really trust.

For some, the analog 45 may have drawbacks, in addition to splitting up the music across four sides (in fact, the original Side 1 of Funkadelic was so long that it actually takes up more than two sides on the 45, stretching into Side 3). The digital 33 has a crisper focus, with more delineation around the different voices and instruments. The analog 45 had slightly fuzzier outlines—but that felt real to me, less cartoony than the defined separation on the 33, creating a sonic space where the (metaphorical) lighting is a little softer and the different elements interact with each other more realistically. Additionally, the vocals on the 45 have a perceptible grain on them. You can hear the guts of the microphone and the mixing board, a slightly limited, electrical sound that was probably just buried so deep in the master tape that we never had the chance to fully hear it until now. I don't think this really takes away from the music; rather, it's an extra facet of accuracy that reveals just how honest this cut is.

Let me return to some technical specs, briefly: Gardner and Vericolli did the analog and digital transfers at 54 Sound Studio in Detroit, assisted by in-house engineer Nick King. Gardner then took the transfers to his DSG Mastering facility in Los Angeles, where he and Rodriguez made both the analog 45 and digital 33 cuts. To further complicate things, there are colored vinyl variants of both cuts, but those should essentially be identical to the black vinyl pressings that I reviewed. All editions were pressed at Metallica's Furnace Record Pressing in Alexandria, Virginia. The 2-LP 45 analog edition comes in a Stoughton tip-on gatefold jacket, while the 1-LP 33 digital is in standard paperboard. Both versions of vinyl come in clear, heavy-duty plastic inner sleeves that almost feel like PVC but couldn't possibly be. (Could they? The Rhino Reserve series uses similar inner sleeves.)

Neither pressing was flawless. As mentioned above, the 33 had some noticeable pressing defects, but the 45 had some clicks and noise here and there as well, albeit nothing too bothersome. None of the discs, 45 or 33, lay perfectly flat, leading to tiny wobbles of my tonearm. Generally, all the discs had silent backgrounds, but I did notice some surface noise at the beginning of Side 3 on the 45 version. Given all these inconsistencies, I suspect the fact that my 45 was cleaner-sounding than the 33 was mere luck of the draw.

Also, I'm a little bummed about the lack of liner notes. (People who write about music will always be bummed about a lack of liner notes.) The original musician credits to Funkadelic are pretty skimpy, with none of the contributors outside the main Funkadelic unit credited due to contractual reasons. It would be nice to see the members of Parliament added, for instance, as well as the numerous guests. And I don't believe a ton is known about the actual recording of this album, so an investigation into that would make for good reading. (If anybody alive can remember it.) Plus, the restoration and mastering process of the Westbound tapes is an absolutely fascinating story, so I would have loved to have Gardner and Vericolli's accounts included as part of the official record. As such, I will probably print them out from the web and make an unofficial liner packet of my own.

In any case, the Org/Westbound's Funkadelic reissue series is off to a roaring start. While the promise of what's to come is pretty exciting, what's here is cause for celebration: Funkadelic has been given a new lease on life, fully restored and sounding more badass than ever. No longer a mere prologue, it's clear that this album was at the bullseye where psychedelia mutated into funk, continuing a progression that began with albums like the Jimi Hendrix Experience's Electric Ladyland, Sly and the Family Stone's Stand!, and the Isley Brothers' It's Our Thing. Whether you're a vinyl addict or a casual listener on streaming, it's pretty cool that this reissue campaign is so comprehensive—Funkadelic has never sounded better, and it's never been easier to get your ears around it.

Org 2-LP 45 RPM (analog source, copy tape to lathe) • Org 1-LP 33 RPM (digital source) • black vinyl (limited colored variants of both versions also exist)

Listening equipment

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980