Reviews: David Forman | Alan Vega

We’ll jump right into the reviews—two for you today. One’s for an album that was lost to time due to record company interference, and the other is for a pair of albums that explored the merging of post-punk with rockabilly.

- David Forman: Who You Been Talking To

- Alan Vega: Alan Vega (deluxe edition) and Collision Drive

No other announcements today, but as always, if you’d like to go beyond a free subscription and support our work, we have a paid tier that’s really just the cat’s pajamas. You’ll get to enter our monthly vinyl giveaways and always have full access to our complete archive. Plus, all the cool kids are doing it.

Now, on with the program.

David Forman: Who You Been Talking To

Review by Ned Lannamann

It’s rare these days to uncover an honest-to-goodness “lost” album—the golden age of reissues has brought us many wonderful things, but it’s also made it seem like we’ve finally reached the point where there are no more stones left to turn. So when a completed LP that for some reason never saw the light of day is exhumed in full, it’s always a fascinating thing to examine. Why was it shelved? Was it actually finished or just abandoned? Was the work flawed, or was it just a victim of plain bad luck?

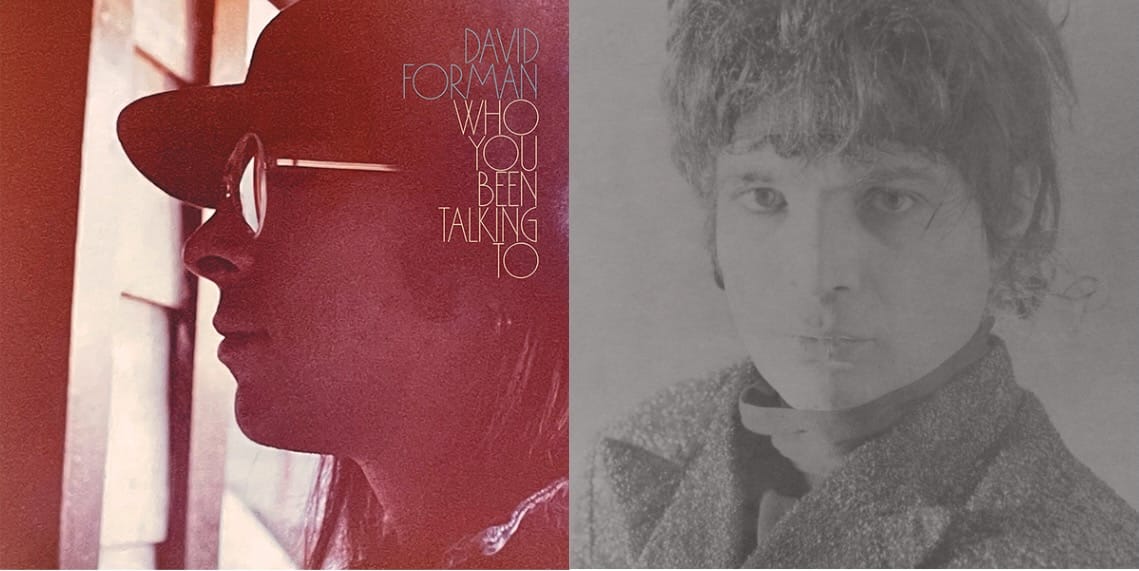

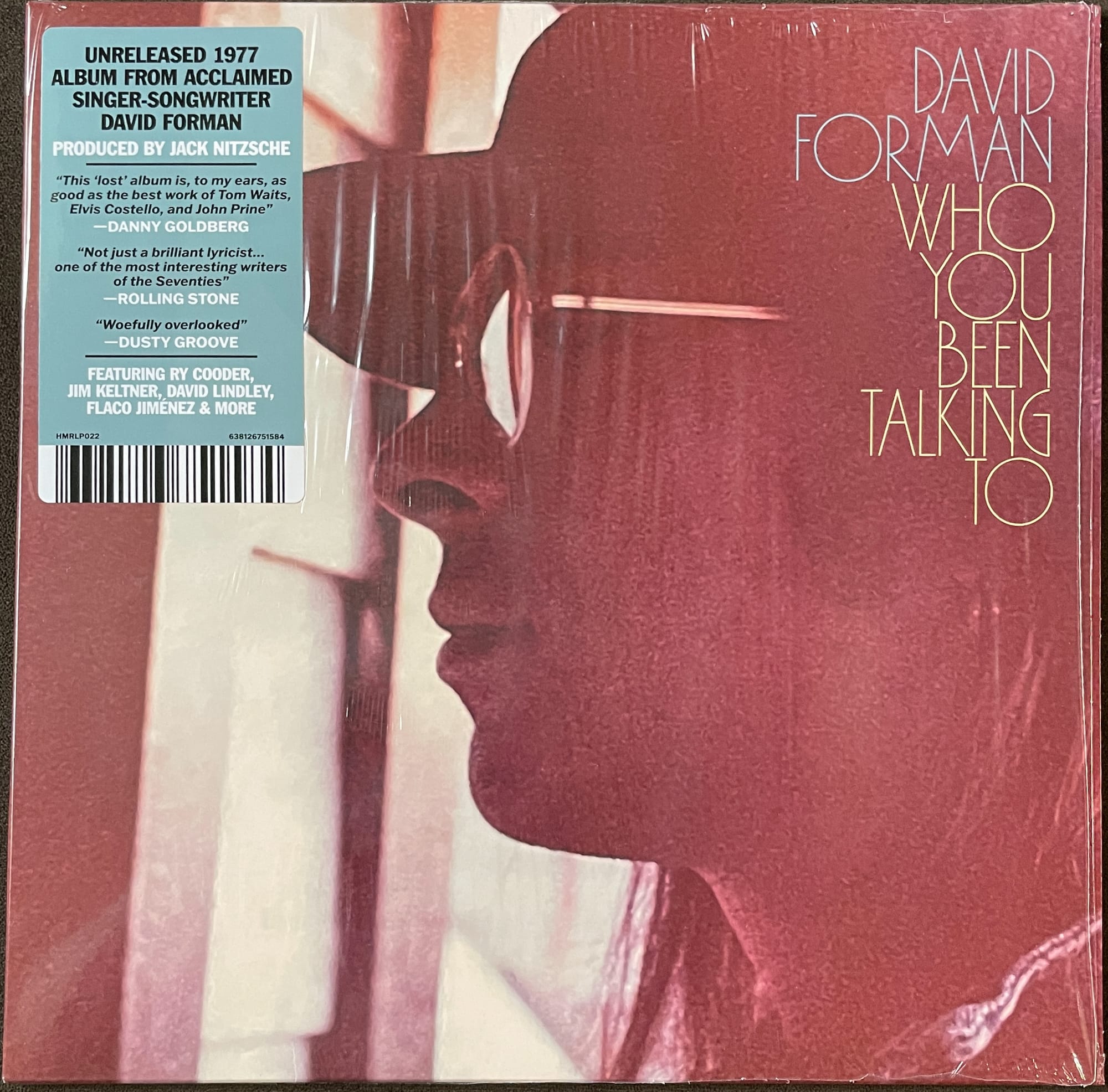

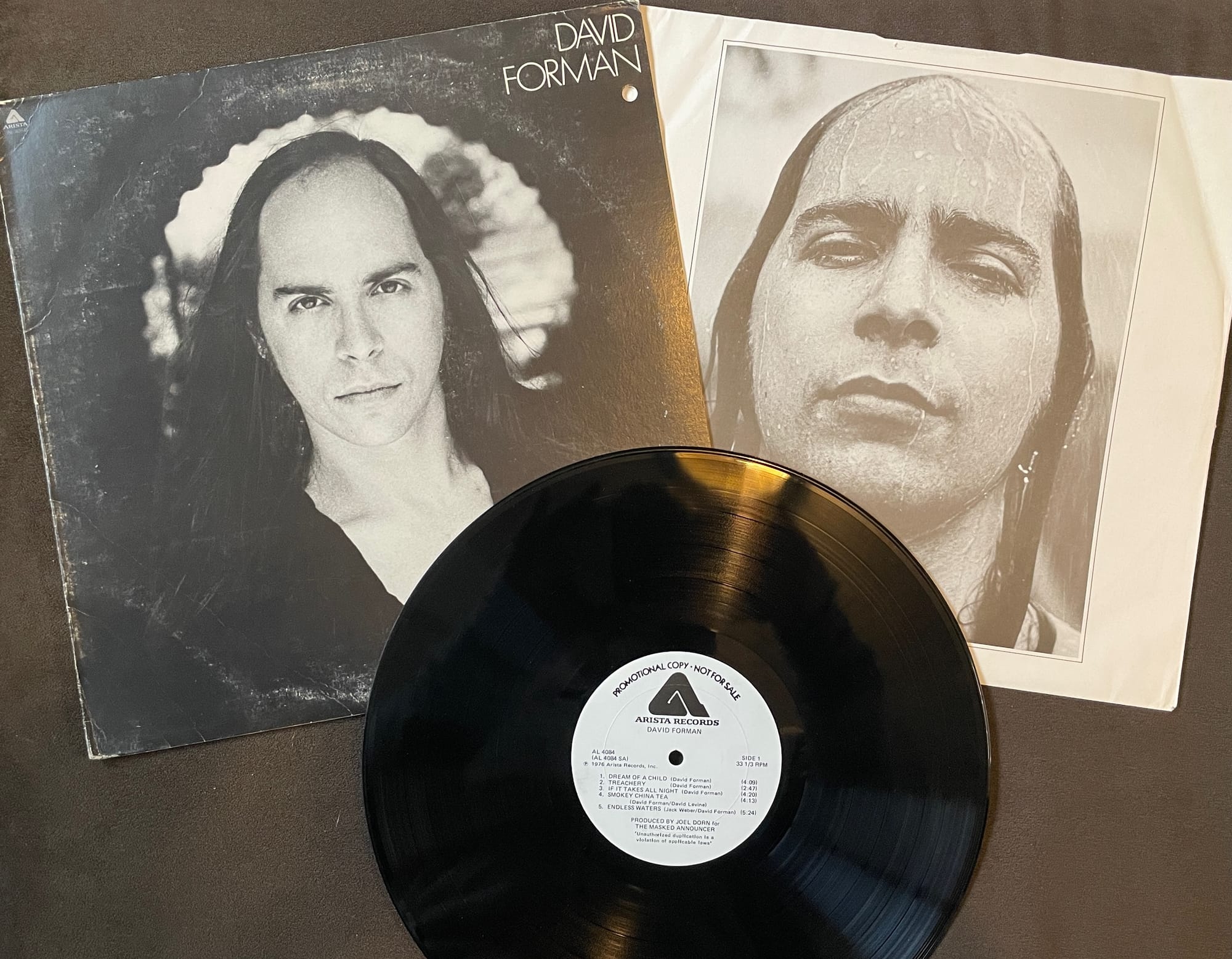

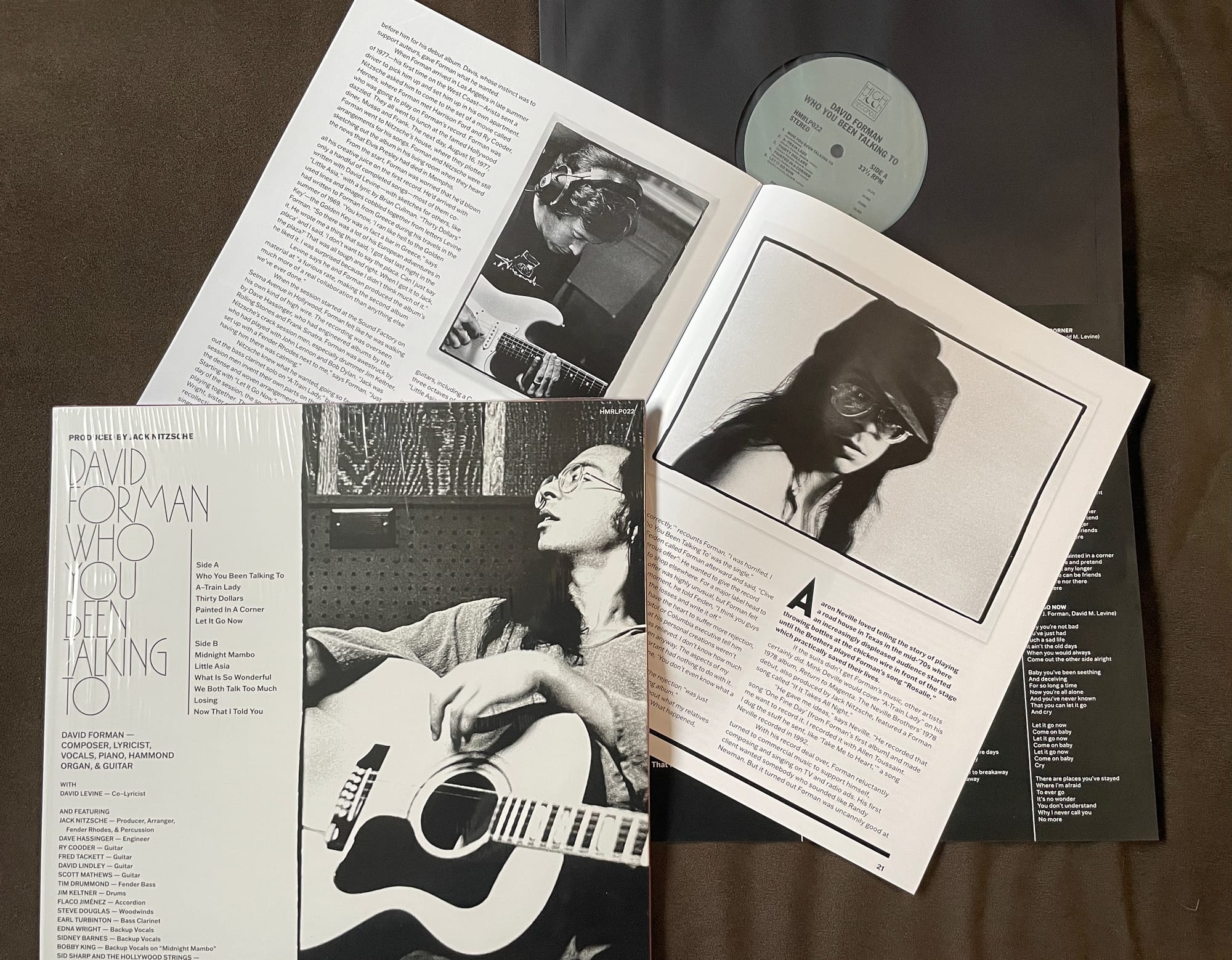

In the case of Who You Been Talking To, the just-released lost album by ’70s singer/songwriter David Forman, the answer to that last question is: bad luck, and plenty of it. Forman was signed to Arista Records and released his self-titled debut album in 1976. It got its share of positive reviews, including a rave in Rolling Stone, but did little to excite radio or the charts. So when Forman delivered the follow-up to Arista label head Clive Davis in 1977, Davis elected to pass, offering Forman the chance to shop it around elsewhere. Forman was devastated by the rejection and couldn’t summon the confidence to find another home for it. He took the tapes back and called it a day on his major-label recording career.

Music journalist Joe Hagan—author of Sticky Fingers, the terrific biography of Jann Wenner—came across the David Forman album via his regular listening group of friends, and he and members of that group tracked the man down, asking Forman the rumors of an unreleased second album were true. Indeed they were, and once a few more pieces fell into place, Who You Been Talking To finally saw the light of day last week via High Moon Records, with a nice chunky booklet featuring thorough liner notes from Hagan.

Forman’s biography, both before and after his ill-fated stint with Arista, is a fascinating one. He was friends with Aaron, Charles, and Cyril Neville and jammed regularly with the musicians before the Neville Brothers became a worldwide concern; “If It Takes All Night” appears on the Nevilles’ 1978 debut album. Forman was also clandestinely involved with Philippe Petit’s 1974 high-wire crossing between the Twin Towers (alluded to in the back cover photo of David Forman, taken by famed photographer Peter Hujar, with whom Forman was close friends for many years). In the ’80s, Forman sang the Tums jingle and made his living through music in advertising, also going on to form the band Little Isidore and the Inquisitors. Some songwriting royalties trickled in—Marianne Faithful, among others, have covered his tunes—but for the most part Forman was content to stay out of the spotlight.

All of the dominoes, then, are set up for the newly rediscovered Who You Been Talking To to be an utter revelation. It isn’t quite that, but it is a remarkably rewarding album of top-tier pop craftsmanship. It was recorded in Los Angeles with Jack Nitzsche producing, and it includes contributions from Ry Cooder, Jim Keltner, David Lindley, Tim Drummond, Fred Tackett, and others. One wonders what Clive Davis must have been thinking. Reportedly, he didn’t hear a single he could market and was unhappy with Nitzsche’s production. But to be unwilling or unable to sell a record of this caliber in the environment of the late ’70s demonstrates a failure of imagination and effort on the part of the business end of things—as, most assuredly, the artistic end has fulfilled its part of the bargain.

It’s all the more ironic because, to my ears, Who You Been Talking To is a substantially better album than David Forman. The first effort is a series of slow ballads performed by Forman on piano with little augmentation, in some ways sounding like a series of demos. While Forman’s lyrics are interesting, the molasses-slow melancholy grows monotonous over the course of the album. Who You Been Talking To, on the other hand, is a much more dynamic and varied listen. It has all kinds of musical styles on it, from the sax-driven slow jam of the title track to the upbeat ’50s-style 12/8 rock of “Now That I Told You,” to the New Orleans shimmy of “Midnight Mambo,” no doubt influenced by Forman’s collaborations with the Nevilles. Forman’s vocals reflect his range and diversity, echoing not just Randy Newman—a heavy influence on the first album—but Dion, Felix Cavaliere, and even Billy Joel, who is probably the best point of comparison for the level of pop songwriting Forman achieves. Despite the LA backdrop of the recording sessions, Forman remains very much a New York artist, and his music is deeply anchored in doo-wop, the Brill Building songwriters, and girl-group sounds.

The physical album master did not exactly survive to this current release, as I understand it. In 1977, Forman sent the album reels to Saturday Night Live musical director Hal Willner, who let the tapes languish in his office for decades. Per Hagan’s liner notes, it sounds to me like this was the only known extant copy, and upon Willner’s departure from SNL, it made its way back to Forman in the early 2000s. Forman had it transferred to CD but then lost the tapes during a move. That CD is what Hagan’s friend group heard initially and what got the High Moon crew interested in releasing it. Around that time, Jack Nitzsche’s son, Jack Nitzsche, Jr., found two tape reels in his father’s archives. They turned out to be rough mixes of the album, and those reels are the source for this current edition. (One song, “Painted in a Corner,” didn’t appear on the Nitzsche reels, so that was sourced from Forman’s earlier CD transfer.)

I can’t say whether the Nitzsche rough mixes are the same as what were on the tapes that ended up in Willner’s office, or whether completed album mixes were ever made and submitted to Davis. I can say that the music on the vinyl version sounds very good but is noticeably not quite at the level of a finished, mastered major-label studio album circa 1977. There is a slight distance to the sound, with occasional flecks of distortion, and a slightly gauzy sonic profile that is lacking a certain crispness but still conveys the musical elements adequately. Once in a while, there are dropouts in the left channel (most noticeable on “A-Train Lady”), and “Painted in a Corner” has a higher level of tape hiss and lower fidelity than the rest of the album. But these sonic observations are irrelevant—truly, irrelevant—when discussing the recovery of a lost work such as this. It’s a miracle it exists at all.

In fact, the more I listen to Who You Been Talking To, the more I genuinely don’t understand Clive Davis’s strategy. “Let It Go Now,” a yearning torch song, is a decided highlight that could have made a play for pop and rock radio. And “Little Asia,” another top-notch ballad, could have become a standard, as it’s the kind of sturdy, well-built composition that’s perfectly suited to interpretations by other singers. But the music business has never made a whole lot of logical sense, and what makes a song click with listeners is a complete mystery that has befuddled suits in boardrooms ever since the first recording contract was ever signed. And while it’s unfair that Who You Been Talking To missed its shot the first time around, the songs on David Forman’s fine second album have, nearly 50 years later, finally been given a fighting chance. I doubt very much the world will be unreceptive this time.

High Moon 1-LP 33 RPM black vinyl

• David Forman’s unreleased album recorded in 1977 for Arista Records and rejected by Clive Davis

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single pocket

• Inner sleeve: Black poly-lined

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: 24-page booklet with photos and comprehensive essay by Joe Hagan, plus a separate double-sided lyric insert

• Source: Digital transfers of rough mixes found in Jack Nitzsche’s archives (“Painted in a Corner” from a lower-quality digital transfer of the original album reels)

• Mastering credit: Steve Addabbo at Shelter Island Sound, New York, NY (“Painted in a Corner” mastered by Dave Darlington)

• Lacquer cut by: Paul Gold at Salt Mastering, Brooklyn, NY; “Salt” in deadwax

• Pressed at: Memphis Record Pressing, Memphis, TN

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A- (disc was slightly dished)

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: None.

Listening equipment:

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980

Alan Vega: Alan Vega (deluxe edition); Collision Drive

Review by Robert Ham

Even as he was terrifying audiences, thrilling critics, and planting the seeds for the coming wave of post-punk with his band Suicide, Alan Vega was thinking about his next move. “No one has taken country and western and rockabilly into the future,” he told NME’s Richard Grabel in 1982. “I wanted to do it with a little newness about it.”

The influence of early rock ’n’ roll was already evident in Suicide classics like “Ghost Rider” and “Rocket USA.” But when Vega stepped out on his own for his first two solo albums, 1980’s Alan Vega and 1981’s Collision Drive—both of which were reissued last week by Sacred Bones—he replaced the hissy throb of Martin Rev’s electronic backing with a hopped-up, stripped-down approach that paid homage to forebears like Elvis Presley and Gene Vincent while still sounding like musical missives from some not-too-distant future. Those qualities don’t necessarily make either album particularly great, mind you. Both are fascinating entries into Vega’s slim but varied discography with moments of brilliance, but overall they are often draining to listen to.

Alan Vega is the most Suicide-like of these early solo efforts. Vega recorded it all with Phil Hawk, who contributes all the guitar and bass on the album. The rhythm tracks are handled by drum machine or a minimalist trap kit, usually just a thumping kick drum. Throughout, Vega, who produced the LP, throws in almost-psychedelic touches, like the blown-out piano licks that jump from one channel to the other on “Love Cry” and the reverb slathered on to every second of “Bye Bye Bayou.” And like most Suicide tracks, there’s forward motion but no destination in mind. Vega hits on one rhythmic idea and drives it into oblivion. It’s the kind of music that could lead one into a trance state or a panic attack.

The only gear change to be found on Collision Drive is the arrival of a full backing band made up of guitarist Mark Kuch, and drummer Sesu Coleman and bassist Larry Chaplan of the glammy band Magic Tramps. Vega sounds somewhat loosened up by having these other players in his corner. That’s especially true of the updated version of “Ghost Rider” featured on the album. The terrifying vision that he and Rev originally concocted on Suicide’s 1977 debut was now closer to the titular character’s comic book origins, all bright colors, swinging chains, and a key lyric change that finds America “fighting” rather than “killing” its youth.

Vega couldn’t leave the dark alleyways of Suicide entirely. The album closes with “Viet Vet,” a nearly 13-minute slow blues about an amputee former soldier whose already troubled life completely falls apart after returning home from combat. Like its closest point of comparison, Suicide’s “Frankie Teardrop,” the song is a truly disquieting piece of work and one of Vega’s finest hours as a songwriter and vocalist. It can be a bit of a grind to get to that track, as the rest of the album follows the same repetitive pattern as Alan Vega, but the explosive payoff is worth it.

Josh Bonati, the engineer responsible for remastering these albums for Sacred Bones, had his work cut out for him. If the story Vega told is to be believed, the music—at least on Collision Drive—was mixed within an inch of its life. “That's a month and a half nervous breakdown you're hearing,” he told NME. “The recording was nothing… but the mixing was insane. I was spreading the sound out. I was minimalizing it, actually shrinking the sound but doing something to the shrink that spreads everything out.”

The soundstage on both albums is fairly wide, with the music coming at the listener from a variety of odd angles, like the harmonica melody and drum machine pulses on Alan Vega’s “Ice Drummer” that are both ever-so-slightly out of phase. Bonati leans a little harder into the music’s tense qualities where it sounds like Vega and his crew are closing ranks. The deeper low end courtesy of Chaplan’s bass on Collision Drive is the only thing relieving some of the pressure. Or just listen to the differences between the finished versions of the material on Alan Vega and the demo versions included with the deluxe edition of the reissue. Vega still gave these rough tracks dubby effects, but they sound far more relaxed in execution.

The impact of these albums remains relatively minimal, even if “Jukebox Babe” from Alan Vega did become a hit in France and help land Vega an eventual contract with Elektra Records. I don't know that these reissues are going to move the needle considerably outside of already established fans of Suicide and Vega. Though I found them slightly wearying to listen to multiple times over for this review, both records are important as snapshots of Vega’s musical mindset in the early ’80s.

Alan Vega: Sacred Bones 2-LP 33 RPM ice-blue vinyl

• Deluxe edition of Alan Vega’s 1980 solo album with second LP of demos

• Jacket: Direct-to-board gatefold

• Inner sleeve: Printed paper

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: Single-page insert with album credits

• Source: Unknown but likely digital; “remastered from the original tapes”

• Mastering credit: Josh Bonati at Bonati Mastering, New York, NY

• Lacquer cut by: Unknown

• Pressed at: GZ Media, Czech Republic

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

Additional notes: Single-disc version is available on black, limited magenta, or limited silver and magenta vinyl; deluxe edition is also available on limited magenta with black splatter vinyl.

Collision Drive: Sacred Bones 1-LP 33 RPM red vinyl

• Remastered edition of Alan Vega’s 1981 solo album

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single-pocket

• Inner sleeve: Printed paper

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: None

• Source: Unknown but likely digital; “remastered from the original tapes”

• Mastering credit: Josh Bonati at Bonati Mastering, New York, NY

• Lacquer cut by: Unknown

• Pressed at: GZ Media, Czech Republic

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: Black vinyl and limited “silver and red collision” vinyl versions are also available.

Listening equipment:

Table: Cambridge Audio Alva ST

Cart: Grado Green3

Amp: Sansui 9090

Speakers: Electro Voice TS8-2