Reviews: Faces | Squeeze

As January draws to a close and much of the US is under a blanket of snow, we’re still happily shoveling ourselves out from under a pile of vinyl from Rhino’s Start Your Ear Off Right campaign. Over the month of January, they’ve dropped a ton of vinyl reissues—many in their excellent Rhino Reserve series. But today we’re looking at some of the non-Reserve pressings they’ve put out over the past few weeks. And they’re darn good ones too.

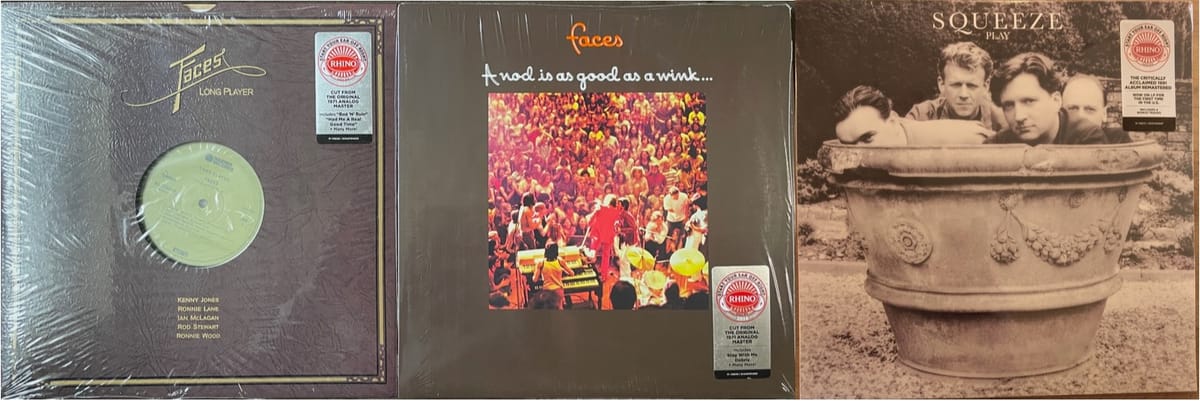

- Faces: Long Player and A Nod Is as Good as a Wink… to a Blind Horse

- Squeeze: Play

Before we get started, here’s yet another reminder that The Vinyl Cut is a reader-supported publication, so if you’d like to join our paid tier and support our work, we would be more than happy for you to do so.

Now, let’s get spinning.

Faces: Long Player; A Nod Is as Good as a Wink… to a Blind Horse

Review by Ned Lannamann

1971 was a banner year for Faces, to say the least. Sure, that was the year their spiky-haired singer Rod Stewart broke through to superstar status when his solo album Every Picture Tells a Story and its single “Maggie May” hit the number-one slots in the US and UK. (Solo album it may be, but Every Picture features Faces guitarist Ron Wood throughout, and the full band joins in on “(I Know) I’m Losing You.”) Even more significantly for the London five-piece, 1971 saw them release two full-length records of their own, amid copious amounts of touring, boozing, and bonhomie.

The two Faces albums from 1971—Long Player (released in February) and A Nod is as Good as a Wink… to a Blind Horse (released in November)—are cut from the same cloth: They’re raucous, good-time rock ’n’ roll, leavened with a congenial folk element and a quintessentially English fascination with American R&B. The pair have been reissued as part of Rhino’s Start Your Ear Off Right campaign for January, and I’m pleased to report that they come in analog-tape cuts that sound just about as good as modern-day vinyl reissues get.

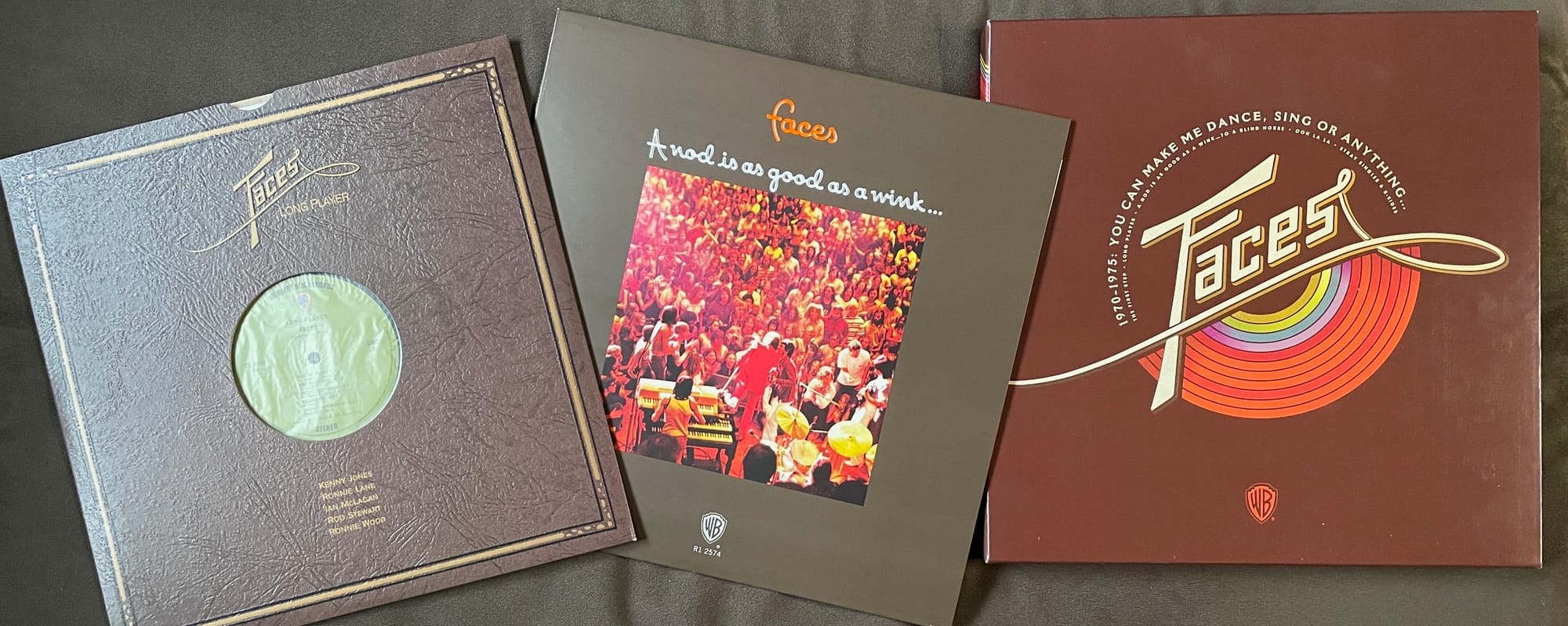

Of course, there are questions. I don’t have the answers to most of them, but let’s get them out of the way. Why have only two of the four Faces studio albums been reissued? (I don’t know, but the year is young and Rhino will have plenty of opportunities to tackle 1970’s First Step, if they so choose; 1973’s Ooh La La was released as a Rhino High Fidelity version in January 2025, so we may not see another version of that one right away.) If these are all-analog, why didn’t they release ’em as part of the Rhino Reserve series, then? (I don’t know, but that series has been increasingly busy, so maybe they wanted to put these out separately to avoid a logjam.) The Faces albums were all released as analog cuts in the excellent You Can Make Me Dance, Sing or Anything box set from 2015, so are these new cuts any better? (I actually do know the answer to that… and you’ll just have to read on and see.)

As I said, Long Player and A Nod Is as Good… are two sides of the same coin, but when played back to back they show how Faces, over just a few short months, developed in confidence, consistency, and drive. Long Player has some filler, while A Nod doesn’t have a trace of fat. Long Player finds the band grappling with the recording process and trying to replicate their live sound in the studio, going even so far as to include a pair of live tracks; A Nod, meanwhile, teams the band with ace producer Glyn Johns, who was able to get right out in front of the band’s muscular, loose-limbed sound and deposit it straight into the phono grooves. Long Player sees the band stretching out in interesting ways, with some high highs but less consistency overall; A Nod allows the band to play to its strengths and perform as a wholly integrated unit, Stewart’s solo ambitions be damned.

Faces, of course, were the second incarnation of the outfit that virtually defined the London mod scene of the ’60s—that being Small Faces, which included bassist Ronnie Lane, keyboardist Ian McLagan, and drummer Kenney Jones. When vocalist/guitarist Steve Marriott left Small Faces in 1969, the remaining three teamed up with Stewart and Wood, dropped the “Small,” and signed to Warner Bros. Records. At their strongest, Faces thrived at the midpoint of the axis between the two poles in the band. On one end, Stewart and Wood churned out boozy, boisterous rock, and at the other end, Lane offered more introspective material, sometimes incorporating folk and country elements and even occasionally taking over the vocal mic from Rod the Mod. Jones and McLagan roamed somewhere in the middle (McLagan also contributed to the songwriting) and were dream teammates for both ends of the axis, offering power and subtlety in equal measure. When the band fully locked in, they charged like a team of bulls.

At the time of Long Player, Faces were not fully happy with the results they’d gotten in the studio thus far, which led to some experimental techniques. “Bad ’n’ Ruin” and “Tell Everyone” were recorded at the Rolling Stones’ Stargroves estate using that band’s mobile recording unit, while “On the Beach” was recorded in Lane’s apartment on a Revox tape machine (and sounds pretty wretched as a result). Two live tracks were also included: an extended live take of Big Bill Broonzy’s “I Feel So Good” that is a bit of a waste, and a stab at the new-at-the-time Paul McCartney tune “Maybe I’m Amazed” that eventually achieves liftoff but has a few fluffs and bum notes along the way. The other tracks were recorded at Morgan Sound Studios, one of the only studios in London that had a bar on the premises, which made the Faces feel at home even if they weren’t at their most productive.

A Nod Is as Good as a Wink was recorded much more efficiently at Olympic Sound Studios, with Glyn Johns doubling as engineer and producer. His approach was simple and sensible: take a good amount of time setting up the mics so that the instruments will sound their best, and then just let the band rip. The album is nearly 10 minutes shorter than Long Player, but with the rough edges sanded off, it’s a far more streamlined and potent effort.

These new Start Your Ear Off Right pressings were cut from the Warner master tapes by Chris Bellman. Simply put, they are terrific pieces of wax. On Long Player, the Stargroves recordings sound absolutely spectacular, particularly “Tell Everyone,” where the natural sound of the room places the listener in the center of the action. The ensemble is perfectly balanced with a hefty but not overpowering bass, and a soundstage that serves realism and musicality above all else. The same goes for A Nod, which is even more dynamic and action-packed, perhaps because of the shorter album sides. “Stay with Me,” the album’s explosive highlight, sounds positively extraordinary, with the buzzing attack of Wood’s rhythm guitar slicing just right, Lane’s bass carving subterranean passageways beneath the tune, and McLagan’s Wurlitzer achieving what might be the platonic ideal of an electric piano tone (eat your heart out, Fender Rhodes).

I compared the new Bellmans to my original US green label pressings, which were mastered anonymously at an unknown facility; by coincidence, my copies were both pressed at Columbia’s Terre Haute pressing plant. These are dynamite cuts, particularly A Nod, which has an enormous bass presence and fills the room with excitement. The sonic imaging is a little fuzzy and flared-out, without the sharpness of detail that I found on the Bellman cuts, but they are remarkably enjoyable listens.

I also compared them to the pressings in the You Can Make Me Dance, Sing or Anything box set from 2015, which were cut by Kevin Gray at Cohearant Audio; it’s widely believed that these were cut from the analog masters as well. These are splendid renditions that have received raves from Faces fans, and I have always been more than happy with them, although the MPO pressings in my copy of the box are not perfect (Long Player is pressed distractingly off-center, for example). The Gray cuts have a decided strength: They offer more separation between the different instruments, with substantially more space and definition around them.

However, in a direct shootout with the new Bellmans, the 2015 Gray cuts are, to my ears, slightly clinical, working at odds with the ensemble feel that is so important to these records and sucking out some of the air in the process. The Bellman cuts tone down the isolation in between instruments just a tad in favor of a more integrated, natural sound. And I found that I preferred Bellman’s approach; it sounded more musical and spontaneous. For instance, the ecstatic sound of “Stay with Me” that I encountered on the Bellman A Nod is somewhat neutered on Gray’s, missing that magic glow that takes it to the level of transcendence. Truth be told, though, all three cuts—the OG greenies, the Gray box set cuts, and the new Bellmans—are pretty spectacular.

I think the only major point of comparison I’m missing are original UK cuts, which would have been cut from the UK master tapes. Without any inside knowledge, I am hazarding a guess that the three cuts I’ve mentioned were all taken from a 1:1 copy that was duplicated in 1971 and shipped over to Warner’s US facilities. To that end, the jackets on the new editions mirror the original US versions, both of which had substantially altered cover art from their UK counterparts. In a perfect world, a reissue would be able to integrate the artwork of both versions, as I think the UK cover art for Long Player is a bit more appealing, and it includes credits and track information that the US version doesn’t. The new A Nod does includes a reproduction of the album’s original poster, a patchwork made up of 300 or so smaller photos and Polaroids—obsessives should take note that it is a little smaller than the original (it’s still pretty enormous, at 2’x3’) and it tragically crops off the outside row of photos. Most of the seedy photos of groupies and band member bums are intact, though.

These are pressed at GZ’s Memphis Record Pressing, and my copies were virtually flawless—not something I can say about every record I’ve gotten from Memphis. In fact, I have nothing to complain about sonically from these new Start Your Ear Off Right pressings whatsoever. I would not have guessed they’d become my go-to, especially with other great choices at my disposal. But until I find those mint-condition UK pressings, these will absolutely be what I put on the turntable when I want to hear one of the most flat-out fun British bands of all time during their greatest single calendar year.

Long Player

Warner 1-LP 33 RPM black vinyl

• New analog remaster of the Faces’ first album of 1971

• Jacket: Replica of 1971 US original, with top-loading die-cut textured jacket

• Inner sleeve: White poly-lined

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: None

• Source: Analog; “cut from the original 1971 analog master”

• Mastering credit: None

• Lacquer cut by: Chris Bellman of Bernie Grundman Mastering, Hollywood, CA; “CB” in deadwax

• Pressed at: Memphis Record Pressing, Memphis, TN

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: Released as part of Rhino’s 2026 Start Your Ear Off Right series.

A Nod Is as Good as a Wink… to a Blind Horse

Warner 1-LP 33 RPM black vinyl

• New analog remaster of the Faces’ second album of 1971

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single pocket

• Inner sleeve: White poly-lined

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: Replica of original poster is included

• Source: Analog; “cut from the original 1971 analog master”

• Mastering credit: None

• Lacquer cut by: Chris Bellman of Bernie Grundman Mastering, Hollywood, CA; “CB” in deadwax

• Pressed at: Memphis Record Pressing, Memphis, TN

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: Released as part of Rhino’s 2026 Start Your Ear Off Right series.

Listening equipment:

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980

Squeeze: Play

Review by Robert Ham

Squeeze has spent the better part of five decades slipping between genres, rubbing shoulders with the pub rockers, punks, and new wave artists of the late ’70s and early ’80s but never really sounding like they fully belonged in any of those camps. As the UK band progressed through the decades, their sound settled into a power-pop/rock groove but would occasionally and joyfully veer off into country, folk, and music hall.

The only consistent thread tying it all together is the songwriting of Squeeze’s only mainstays: Glenn Tilbrook and Chris Difford. The latter is responsible for the sharp, literate lyrics that usually fret over matters of the heart, while the former fits those frequently wordy verses into undeniably catchy tunes. Their combined efforts, and the nimble work of the musicians that have floated in and out of the band over the years, produced one of the strongest discographies in whatever genre the world sees fit to place them in.

As we home in on the timeline of the band ca. 1991, Squeeze was going through another turbulent spell. Keyboardist Jools Holland quit once again (he previously left the group around 1980 only to rejoin the fold five years later) and they were without a label, having been dropped by A&M during the tour for their 1989 album Frank. The strife thankfully didn’t dull their creative spark by the time they landed a new benefactor in Reprise Records and began work on their ninth album, Play. Instead, Difford and Tilbrook, along with their longstanding drummer Gil Lavis and bassist Keith Wilkinson, responded with some of their strongest material in years.

Much of it is not as immediately grabby as, say, the group’s lone top-20 US hit “Hourglass” (from 1987’s Babylon & On) or their college-radio classics like “Another Nail in My Heart,” but the mood of the record feels as lived-in and cozy as a favorite armchair. With its thoughtful, acoustic-leaning arrangements, Play fits in nicely with the then-current wave of fellow artful pop artists like Crowded House, Sam Phillips, and Michael Penn (who is part of the choir of backing vocalists on “The Day I Get Home”).

The warmth of the record deserves a warm presentation on vinyl, and mastering engineer Chris Bellman clearly understood the assignment. I’ve only ever heard a CD of this album around the time it was released, but I do remember being impressed with how dynamic it sounded, with producer Tony Berg and mixing engineer Bob Clearmountain having a great time playing within the stereo field. On tracks like “Letting Go” and “The Truth,” little playful sonic touches float from channel to channel as if a dub remixer had briefly taken control. All of that is rendered in rich colors on this new vinyl pressing. The soundstage is exciting and lively with a thoughtful balance that keeps every instrument in crisp focus. It’s an absolute pleasure to listen to.

As Squeeze has accepted their current status as a legacy artists, regularly touring and playing primarily material from their first five albums, Play and the equally fine albums that followed have become a footnote in the story of the group. As with so many reissues like this, there’s every hope that folks who aren’t already on board with this era of the band will finally realize what they’ve been missing. And to have the music sounding as good as it does on this reissue will only make the discovery seem that much sweeter.

Rhino 2-LP 33 RPM black vinyl

• First US vinyl edition of Squeeze’s 1991 album with added B-sides

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single-pocket

• Inner sleeve: White poly-lined

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: Eight-page booklet with lyrics and album credits

• Source: Unknown, assumed digital

• Mastering credit: Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering, Hollywood, CA

• Lacquer cut by: Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering, Hollywood, CA; “CB” in deadwax

• Pressed at: Memphis Record Pressing, Memphis, TN

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: Released as part of Rhino’s 2026 Start Your Ear Off Right series.

Listening equipment:

Table: Cambridge Audio Alva ST

Cart: Grado Green3

Amp: Sansui 9090

Speakers: Electro Voice TS8-2