Reviews: Frank Sinatra | Aksak Maboul

As much of the US begins to plunge into a deep freeze, we figured what better time to cozy up with some records that we missed the first time around? This pair of vinyl reissues came out last November but got lost in the crazy shuffle of releases leading up to the holidays, so today we’re looking back at one of the more hyped reissues in recent months and a compilation examining the origins of a Belgian avant-rock project.

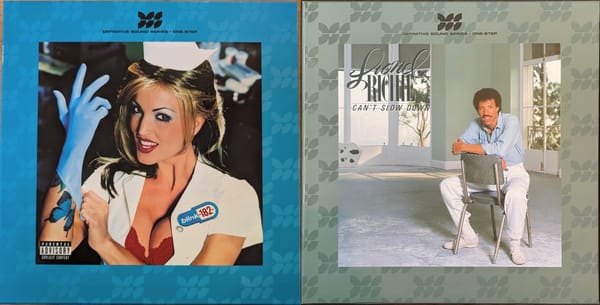

- Frank Sinatra: In the Wee Small Hours (Tone Poet edition)

- Aksak Maboul: Before Aksak Maboul (Documents & Experiments 1969–1977)

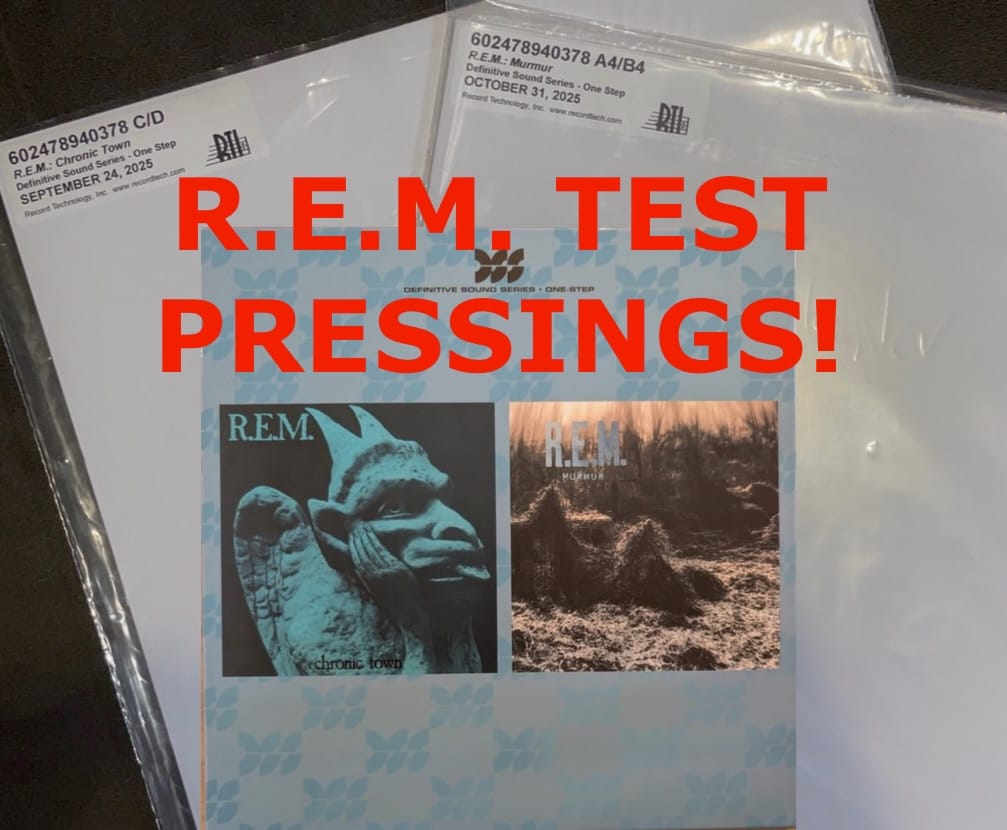

But first, we want to announce last call for our January giveaway. As you’re no doubt aware by now, we’re giving away a set of ultra-collectable test pressings of the new Definitive Sound Series one-steps of R.E.M.’s Chronic Town and Murmur to one lucky member of our paid-subscriber tier. We are closing the window for entries this Sunday, January 25, at midnight Pacific time, so now’s your final chance to click over, upgrade your subscription, and enter to win.

Hope you’re staying warm wherever you are. On to the reviews.

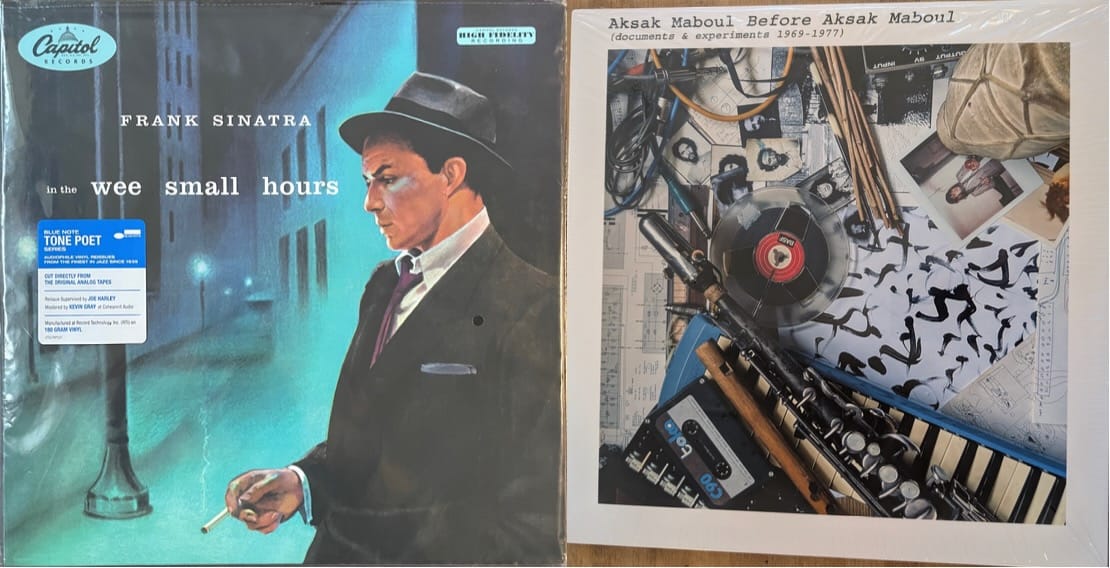

Frank Sinatra: In the Wee Small Hours

Review by Ned Lannamann

Last year gave us an embarrassment of phenomenal vinyl reissues, with near-definitive pressings of many classic albums. Any shortlist of the best of the best, however, would almost certainly have to include the new Blue Note Tone Poet pressing of Frank Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours. Originally released on Capitol Records—not Blue Note, but both labels are owned by Universal now—the mono album’s new all-analog pressing has received overwhelmingly high praise, and it’s been selling out its runs almost as soon as they’re put up for sale. Right now it looks like Universal is temporarily out of copies once again; the Blue Note store currently says orders will ship about seven weeks from now, while the uDiscoverMusic store unhelpfully says “Sorry Sold out [sic].” (Rest assured they’ll make more, it’s just that no one told the webmaster.) But with a coveted copy finally in my hands, I wanted to make my own way through all the fuss that’s been accumulating since this pressing was released in November.

It’s a breakup album, writ large—the breakup album being a quintessential subgenre of the long-playing album format. I could reel off examples aplenty: Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, Marvin Gaye’s Here, My Dear, Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, and Frightened Rabbit’s The Midnight Organ Fight (a personal fave) among them. But the progenitor that set the template goes back as far as 1955, when In the Wee Small Hours used nocturnal solitude as a metaphor to express the theme of a devastating breakup. Nowadays, it gets credit for being the first-ever concept album; a more generous appraisal may even call it the first proper album, full stop, as it was among the first pop records to take advantage of the 12-inch format. In the early ’50s, as shellac 78s gave way to 33 RPM vinyl, pop and jazz records were typically released on 10-inches, with 12-inch long-players usually reserved for more prestigious classical fare. (Even Wee Small Hours’ first appearance on wax was via a pair of 10-inches; the LP—a long one, at nearly 50 minutes—came along shortly thereafter). I think calling In the Wee Small Hours the first-ever album is being awfully generous to Sinatra and Capitol, as plenty of other 12-inch records containing popular music had been released prior to In the Wee Small Hours. But there is merit to the claim that this particular LP was, in many ways, the first of its kind.

“It’s a pleasure to be sad,” Sinatra sings on “Glad to Be Unhappy,” and that phrase more or less sums up the theme of the entire album. It’s a collection of melancholy ballads that whisks their downtrodden, brokenhearted array of moods into a deliciously bittersweet cocktail, with hints of syrup, burn, and crispness to make the liquor go down smooth. The songs are all plucked from the Great American Songbook, with Duke Ellington, Rodgers & Hart, Cole Porter, Hoagy Carmichael, and others contributing tunes. (Only the absences of Irving Berlin and the Gershwins keep the album from being a definitive survey of the most prominent early- to mid-century American songwriters.)

Sinatra’s chief collaborator is orchestrator Nelson Riddle, and In the Wee Small Hours find them only a year or two into their partnership, which would continue on for many years and become perhaps the most consequential singer-arranger duo of the 20th century. Voyle Gilmore produced the album, and his role seems to have been primarily to run the sessions smoothly and to have the music make its way to tape sounding as rich and lustrous as possible. At the time, Sinatra’s marriage to Ava Gardner was on the rocks; they would divorce in 1957. According to Riddle, the turmoil allowed Sinatra to reach a previously untapped, deeper, more sorrowful emotional register with the material.

Riddle uses instrumental restraint to conjure the nocturnal feel and emotional fragility—everything is played subtly, in hushed voicings, as if the music is trying to keep a lid on some of the more volatile feelings that can erupt from a breakup. (Either that, or not wake up the neighbors.) The only bit of high-seas drama appears in “Last Night When We Were Young,” which crescendoes into overwrought conventionality for a few brief moments. (That spell-breaking mood is perhaps not surprising, as it was the only song not recorded during the actual album sessions, coming from a date nearly a year earlier.) Otherwise the strings are muted, the woodwinds are carefree, the rhythm section is unhurried, and the not-infrequent celeste adds a bit of starlight twinkle. Sinatra, too, keeps his cool, letting his natural suavity turn playfully doleful, as if he’s allowing the listener in on the secret that the flipside of any worthwhile romance is vulnerability—if you’re gonna love ’em, you’re gonna have to let ’em break your heart, kid.

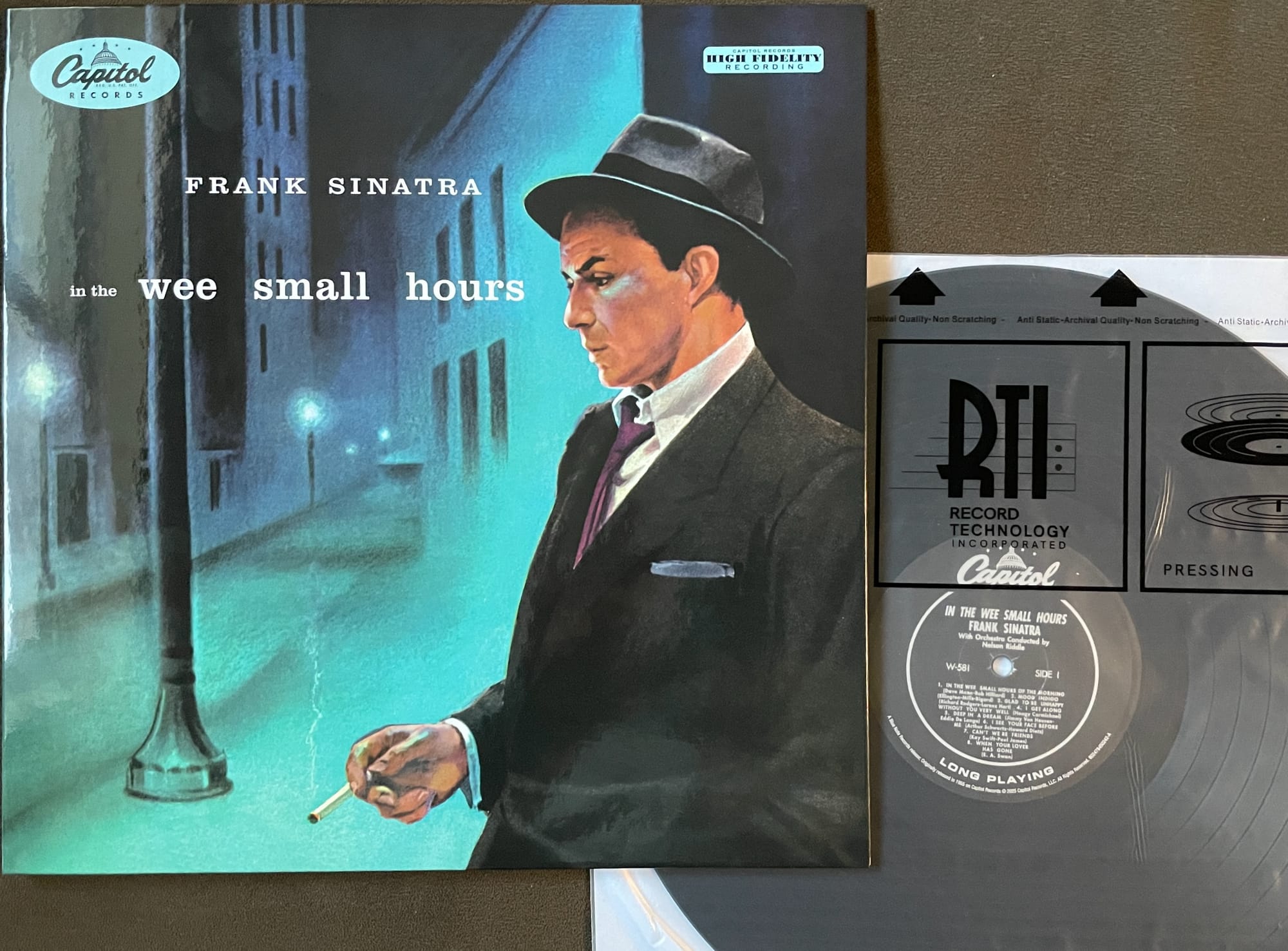

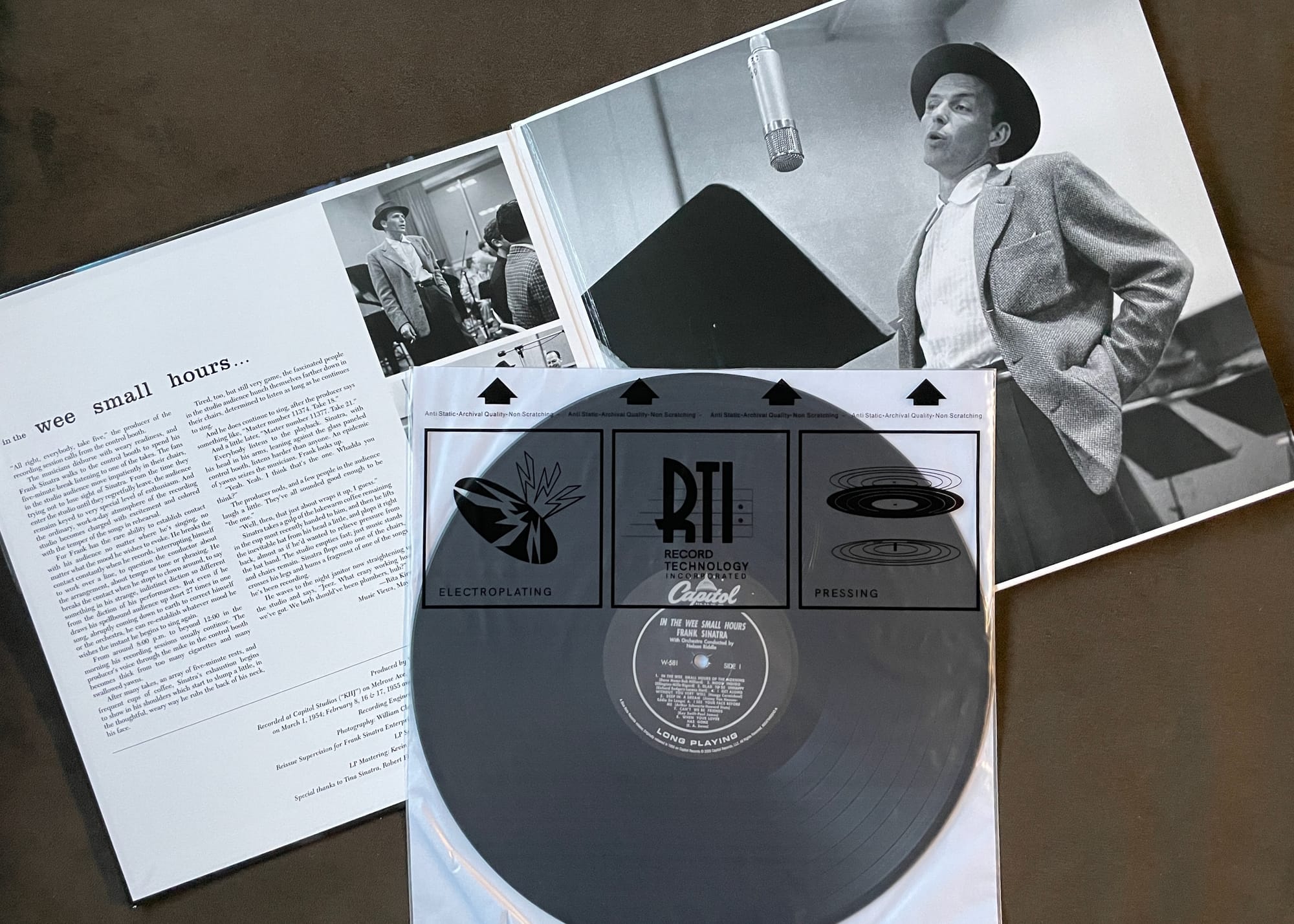

This new pressing comes from a set of tapes that reputedly have never been used before. According to Blue Note producer Joe Harley, two tape machines were rolling at the recording (I’m unclear if he meant during the actual recording session or during the preparation and assembly work for the finished product). One set of the resulting tapes was assembled into the master reels that were used on every previous pressing we’ve heard before. The other was stored away on a set referred to as “phono reels,” which apparently had each track haphazardly stored on archival tapes that also contained stray recordings from artists other than Sinatra—as you can see in the video below. Those phono reels were taken out of the vault and spliced and assembled into a new master tape, which Kevin Gray used to cut this new Tone Poet pressing.

The sound is velvety, round, warm, and lightly smoky, with Sinatra’s voice pulling the orchestration forward like a gentle locomotive. His voice is like a thick-tipped marker diagramming the melody, not merely sitting squarely upon each note but covering it up entirely, even bleeding out a little bit to the notes above and below. It’s a wondrously broad instrument. The mono image is similarly deep and wide, with a remarkable natural presence that rendered my speakers invisible. Rather strikingly, the individual instruments are able to inhabit their own space within the sonic picture, never sounding bunched up or on top of each other. While I didn’t exactly hallucinate a stereo image, this pressing definitely evoked a 3D one. I also had the chance to listen to this pressing through a friend’s old Pilot console setup, whose tube system exchanged some of my system’s clarity for a tremendous amount of warmth. The album sounded wonderfully at home in that environment.

The Gray cut has earned some naysayers, who have criticized the mastering’s forwardness and flashiness, putting emphasis on Sinatra’s voice over Riddle’s backing and removing some of the subtlety that appeared in original pressings. I, however, have no complaints about this cut, because the dimensionality and presence it offers get me absorbed in the music in ways that I haven’t been before. And the virtually silent vinyl, pressed at RTI, permits the cushion-like, nearly narcotic qualities of Riddle’s orchestrations to flood my listening room, with Sinatra gondoliering on top of them with ease. This is a rich, buttery, calming listen that conjures an emotional state and sustains it for the entire duration of the LP. It’s a pleasure to be sad, indeed.

Blue Note Tone Poet 1-LP 33 RPM 180g black vinyl

• New analog mono mastering of Sinatra’s 1955 album

• Jacket: Tip-on gatefold

• Inner sleeve: RTI-branded rice-paper-style poly

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: A brief essay by Rita Kirwan from the May 1955 issue of Music Views is reproduced inside the gatefold

• Source: Analog; “Cut directly from the original analog tapes”

• Mastering credit: “Kevin Gray, Cohearent Audio”

• Lacquer cut by: Kevin Gray at Cohearent Audio, North Hills, CA

• Pressed at: Record Technology Inc. (RTI), Camarillo, CA

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: None.

Listening equipment:

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980

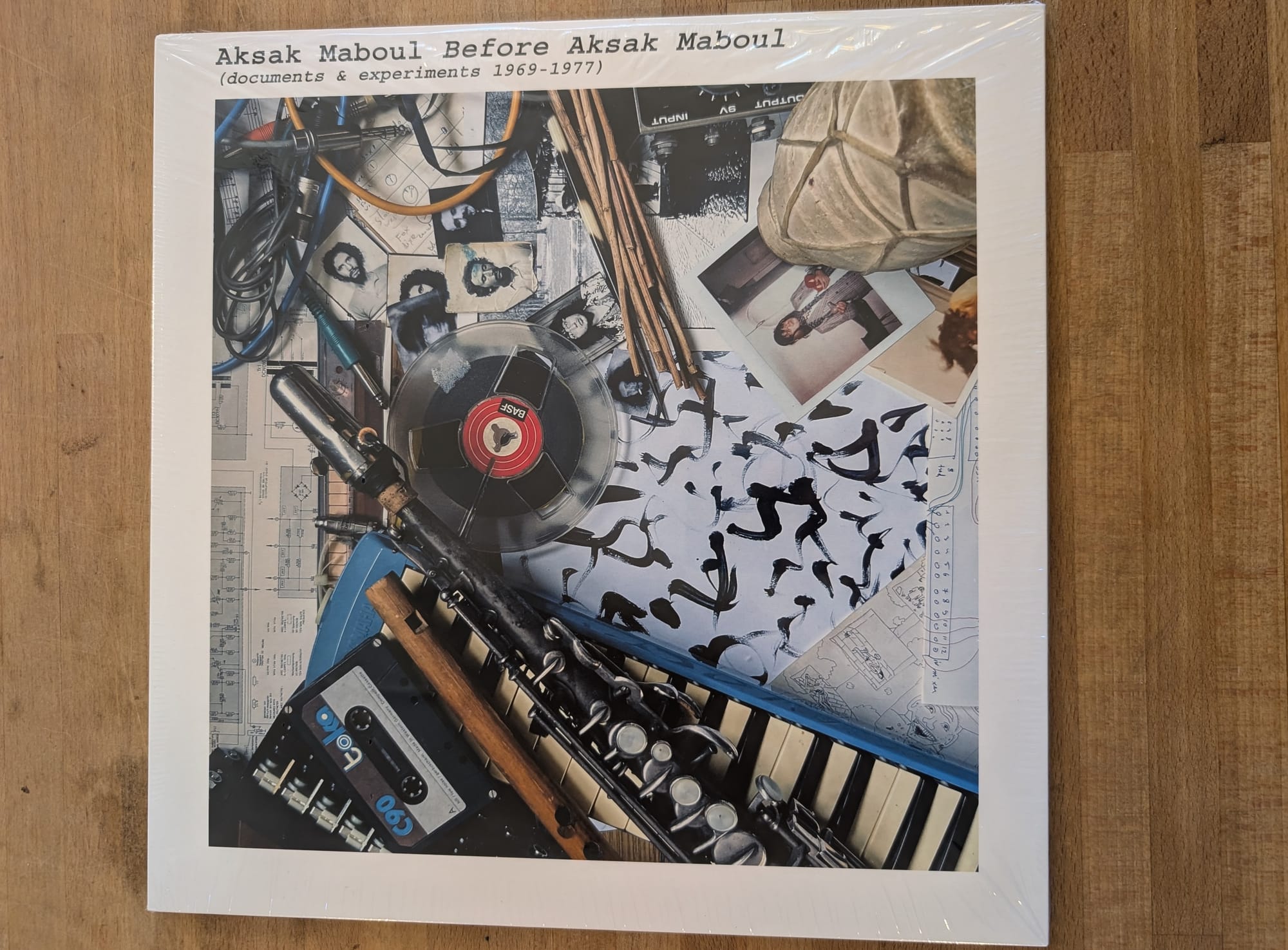

Aksak Maboul: Before Aksal Maboul (Documents & Experiments 1969–1977)

Review by Robert Ham

Aksak Maboul has never been easy to pin down. Founded in the early ’70s by Marc Hollander, the musician and founder of indie label Crammed Discs, this Belgian group could produce facsimiles of the music of North Africa, lounge pop, free-jazz explosions, or noise rock. It all seemed to depend on who had joined the ever-rotating lineup and Hollander’s whims.

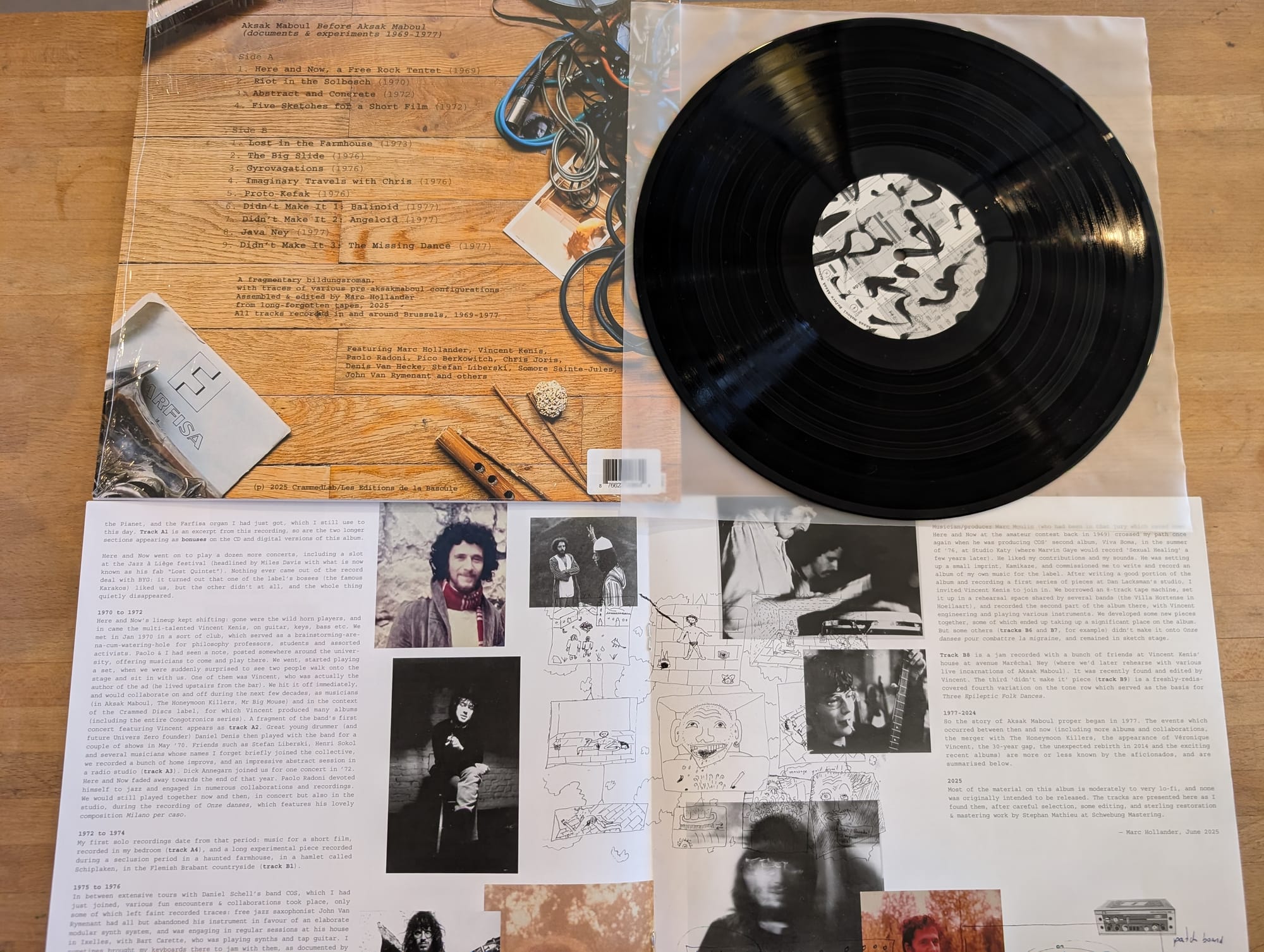

Knowing that, it stands to reason that the collection of archival material Hollander released late last year, Before Aksak Maboul (Documents & Experiments 1969–1977), would also refuse to stay in one sonic zone. The tapes represent the earliest days of Hollander’s creative explorations, from live recordings of his first band to home studio work, captured on various reels and tapes that were uncovered deep in the Crammed archives. The resulting compilation plays like an extended montage sequence, with Hollander’s seemingly unquenchable curiosity leading him toward the first proper Aksak Maboul release, 1977’s Onze Danses Pour Combattre la Migraine.

The most alluring material on this set is the opening run of tracks by Here and Now, the freeform psych-rock band Hollander started with guitarist Paolo Radoni in 1969. The group initially trucked in an exploratory blues-jazz hybrid inspired by the Mothers of Invention and the Soft Machine. But as more members joined the fray (at its height, it was a sprawling 10-piece), their free jazz interests took a stronger hold.

That era of the band is represented by a four-minute excerpt of a rehearsal recording made by Dan Lacksman, the audio engineer and synth enthusiast who would go on to form the pop group Telex. The track is a full-bodied roar of thunderous rhythms from drummers Archie Brown and Michael Johnson, augmented by Hollander’s fluttering keyboard runs and the blurts from the group’s horn section. Just as it truly starts to pick up steam, though, the music fades away to make room for the rest of the pieces on the LP. (A pair of longer excerpts from this same performance are available on the CD and streaming versions of the compilation.)

The other two Here and Now pieces are far less engaging, featuring minimalist squeaks and meandering jazz-guitar skronk, but they do set the stage for the rest of the comp, which often finds Hollander on his own or working with a select few musicians. The tracks tend to be short, squelchy experiments made using an array of modular synths, ring modulators, and drum machines. Sometimes they take on a recognizable form like “Didn’t Make It 2: Angeloid,” a brief tune from 1977 made with Vincent Kenis that could have been snipped out of a Weather Report jam, or “Proto-Kefak,” a 1976 piece reminiscent of John Carpenter’s soundtrack work. In most other cases, the players sound like they are feeling out what noises they can tease from their chosen instruments with no clear goal in mind—interesting in the moment but not terribly memorable either.

As you might imagine, the sound quality of this compilation varies wildly, as it was built from reel-to-reel tapes and cassettes that likely haven’t been touched in decades. Lacksman and Greg Bauchau transferred all of this material to digital files, which were then edited down to the choicest bits by Hollander. It was then up to mastering engineer Stephen Mathieu to bring these scattershot pieces into balance. It’s an impressive feat, even if, at times, it has the qualities of a bootleg with inescapable layers of tape hiss and sonic murk hovering over the music. The whole compilation maintains an appreciable flow without huge leaps in volume from track to track. And while some pieces are more engaging than others and span nearly a decade, it all holds together as a comprehensive document.

As someone who has been enjoying the music of Aksak Maboul since the project was reignited by Hollander in 2014, I’m not sure how often I’m going to pull this disc off the shelf, but I would still recommend it for both longstanding fans and folks looking for an entry point into the group’s music. Here’s a chance to hear Hollander and his collaborators sharpening their skills as players and songwriters, heading towards their more confident and cohesive work within the electrifying post-punk scene in Europe.

Crammed Discs 1-LP 33 RPM black vinyl

• Collection of material recorded by Marc Hollander and various collaborators between 1969 and 1977

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single pocket

• Inner sleeve: Black paper

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: Eight-page booklet with history of project and notes/credits for each track

• Source: Analog; “Retrieved from long-forgotten reel-to-reel tapes and cassettes, transferred to digital by Dan Lacksman and Greg Bauchau”

• Mastering credit: Stephen Mathieu, Schwebung Mastering, Germany

• Lacquer cut by: Unknown

• Pressed at: Unknown

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: None

Listening equipment:

Table: Cambridge Audio Alva ST

Cart: Grado Green3

Amp: Sansui 9090

Speakers: Electro Voice TS8-2