Behind the Presses at Polysom

The Brazilian manufacturing plant’s Clássicos Em Vinil series brings MPB and Tropicália to a new generation.

Music discovery has never been easier these days, from online sleuthing to physical crate-digging. While the majors have begun to take vinyl seriously again, it’s been the smaller independent labels that have been most responsible for reissuing overlooked treasure troves, often of albums that barely made a mark. With a deluge of these labels active and thriving these days, we’re putting a spotlight on their efforts in revitalizing incredible catalogs and movements from around the world—efforts that have made crate-digging not just easier but an all-consuming pleasure.

In the 1960s, bossa nova opened Brazil’s borders to the world. But it was the subsequent arrival of música popular brasileira, aka MPB, that introduced a wider vocabulary of contemporary Brazilian music—such as that made by the countercultural Tropicália movement, which challenged the cultural borders planted by a newly installed military dictatorship. From those roots, MPB developed sounds that range from baroque to anarchic, with Brazilian artists unafraid to resist the cultural repression of the country by ushering in pop, rock, and the avant-garde.

Fortunately, the history of MPB has gotten its global due in the last decades through lavish reissue campaigns by labels like Mr Bongo and Luaka Bop; raving ambassadorship by musicians-slash-music nerds like Madlib, Flea, and Brazil’s own Ed Motta; and documentaries like 2012’s Tropicália, in which significant artists like Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil explain with their own words what it was like to make music under teething persecution. (You can watch the film for yourself on YouTube, though we can’t attest to the accuracy of its subtitles.)

As such, modern appreciation for MPB has thrived in and out of Brazil. Rio de Janeiro–based vinyl manufacturer Polysom has done its part with the landmark Clássicos Em Vinil series, launched in 2010 with a reissue of the summery Jorge Ben samba masterpiece A Tábua de Esmeralda. Subsequent installments in the series have since made their way onto the Kallax shelves of music lovers around the world without them needing to fork out $300 for an original VG copy. (But as they’re manufactured in, and exported from Brazil, shipping these records from their retailers will still cost you, and Polysom’s official store appears not to offer international shipping. Light in the Attic and Mr Bongo have endeavored to import some of these titles into the US and UK respectively, but those are priced a little higher, too, presumably to cover import costs.)

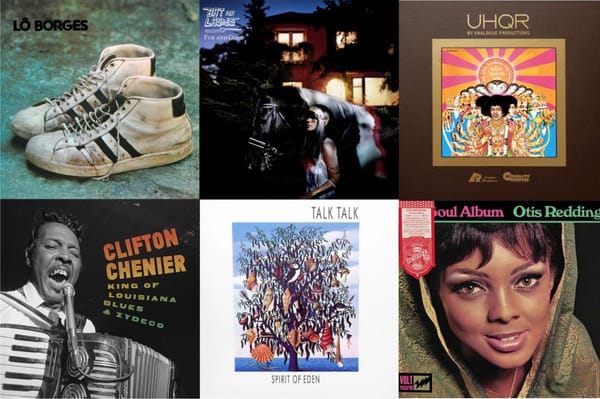

Since 2010, there have been more than 100 titles in the Clássicos Em Vinil series—from a young Gal Costa’s kaleidoscopic psych-pop to the sprawling Clube de Esquina by Milton Nascimento & Lô Borges—and reception by those with copies has been mostly positive. Predictably, some are left speculating on the provenance of source material and remastering (digital transfer vs. analog tape, etc.). Still, I can’t imagine my own reissue copy of A Tábua de Esmeralda sounding any better than it already does.

Additionally, for those not tuned into Polysom’s treasures all this while, it has been a bit of a game of catch-up: These titles don’t last long on the market, with Discogs prices for some reissues scaling up close to the luxurious heights of OGs, which get scarcer as the years pass. As Polysom owner João Augusto explains, “Demand is greater than our manufacturing capacity.”

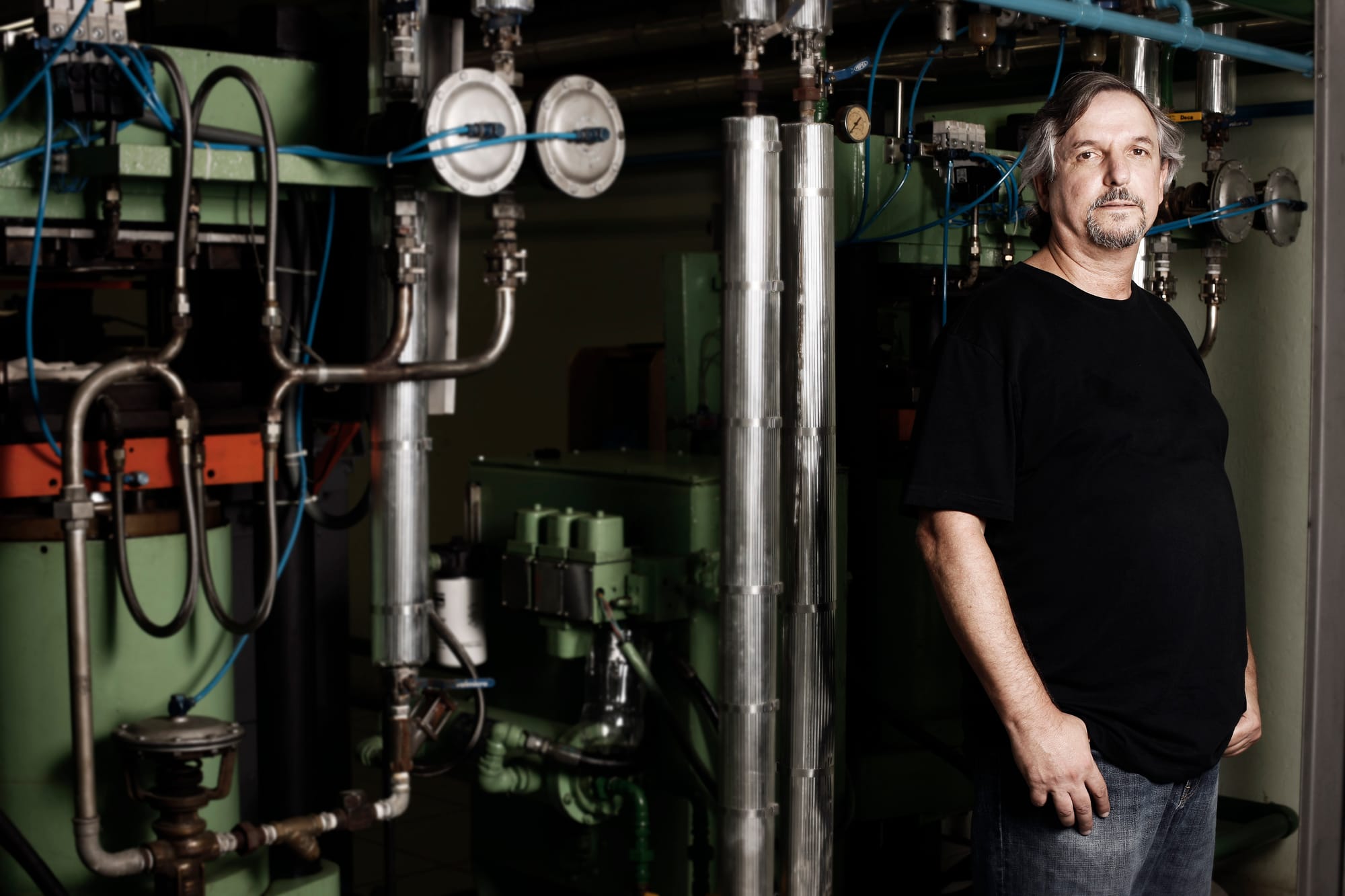

Founded in 1999—when vinyl was at a consumer-market rock bottom—Polysom today operates as a pressing plant and manufacturer for vinyl and, more recently, cassette tape. They’re not a label, as Augusto emphasized in our email conversation, though running their own vinyl series like Clássicos Em Vinil has certainly placed them a step further than, say, GZ Media or Optimal.

The plant was founded to service local artists and labels, along with those in wider South America. The business sailed through modestly in the 2000s until it couldn’t anymore—that’s when Augusto, a former major-label executive and founder of independent record label Deckdisc, says he swooped in to purchase the company and its premises to assist his main venture.

As Augusto reveals to The Vinyl Cut, Clássicos Em Vinil was an attempt to reintroduce Polysom into the South American market, with Augusto leveraging on his major-label connections to retrieve master tapes that “were becoming damaged in the warehouses.” He certainly didn’t half-ass it: Prior to its launch, Augusto consulted with experts in the US to guide his team on the nitty-gritty of making new, quality wax.

The impact and popularity of Clássicos Em Vinil beyond the region was unexpected, though he affirms it will never change the way Polysom operates. The rest of the world will simply have to manage expectations.

Below, we speak with Augusto as he talks about the origins of Polysom and Clássicos Em Vinil, what it was like restarting a vinyl manufacturing business in 2009, his love for MPB, and whether certain high-demand titles will ever see the light of day again. For now, sadly, there’s no repress of Clube de Esquina on the way (though he explains why).

As Augusto is not a native English speaker, the interview was conducted entirely over email. It is also edited and condensed for clarity. Special thanks to Piky Candeias for setting up the interview and assisting with Augusto’s answers.

THE VINYL CUT: Hi, João! Please tell us about yourself and what you do at Polysom.

JOÃO AUGUSTO: I am 69 years old and have a background in journalism and music production. For many years I was the A&R director of record labels both Brazilian (Abril Music) and international (Polygram).

In 1998, we started the independent record label Deckdisc, and in 2009, we bought Polysom and started to refurbish its vinyl factory, which had been closed. We carried out this process for two years. For a long time, being the only plant of its kind in Latin America, we had to resolve several issues with the help of other factories around the world. We can say that in 2011, we started manufacturing truly high-quality records. Currently, I am one of the owners and manage Polysom as president.

Brazil is an island in terms of information and equipment—we couldn’t improve anything [on our own]. I would go to sleep giving up and wake up with some hope that kept me going. Nobody was manufacturing press machines: There was no Phoenix Alpha, no Newbilt, nothing. Our only resource was to refurbish what we had.

At a certain point, I decided to travel the world to learn. I dragged my whole team, made up of very good and professional people, along with me. That’s when I met highly empathetic professionals who helped me generously.

The biggest problem we faced, for example, was electroplating [i.e., the process of creating metal stampers to press vinyl records]. In Jay Fairfax [former mastering & electroforming manager of California plant Rainbo Records, now defunct] and Desmond Naraine, owner of Mastercraft Record Plating in New Jersey, I found two geniuses with all the support I needed. My debt to them is immense.

We refined the process until we reached what we wanted. At the time, everybody around me called me crazy. Today, they try to call me clever, but I insist on denying it: I am crazy, indeed.

Tell us more about Polysom’s current operations as a manufacturing plant.

Polysom is a factory with a very old-fashioned style. It makes its own PVC mixture (we don’t use ready-made pellets) and the presses are all refurbished and manual. Compared to today’s processes around the world, Polysom is quite artisanal, but we still manage to manufacture products that have been recognized [as] good quality in several countries that release Polysom’s titles.

We manufacture an average of 250,000 units per year for all labels and independent artists, and some major labels. Fundamentally, due to the taxes established by law, and in order to have attractive prices, we only manufacture products with Brazilian music.

How many reissues of older albums are manufactured at Polysom, as compared to new releases?

It's important to clarify: Polysom is not a label, it’s a vinyl factory. It produces in two formats: licensing old or new albums and distributing them by itself, or simply manufacturing them.

Since the beginning of its operations, more than 200 classic Brazilian music titles have been licensed, including from our own label, Deck. But with the increase in demand, we began to pay close attention to manufacturing clients, since Polysom’s objective has always been to serve independent artists.

We only licensed because at that time the major labels didn’t show interest in managing this, and we needed titles on the market in order to get recognition for the project. The wonderful titles we have licensed, combined with excellent press work, led to vinyl being taken very seriously in Brazil and no longer treated as a luxury for collectors.

[Our] licensed discs are sold worldwide. Manufacturing is restricted to South America, with a strong emphasis on Brazilian territory. Today, there are more than 170 factories worldwide—when we started there were 42, and only 14 in our full-service format: lacquer cutting, electroplating, and pressing.

2009 was still fairly early for any kind of vinyl revival in most parts of the world. Why vinyl?

In Brazil, there was almost no vinyl movement during this period, but in some countries it persisted in the market. The major record labels abandoned the format. Independent labels like Deckdisc needed to produce vinyl as their artists had requested for it.

So, the most important factor that led us to acquire and open the doors of Polysom was to manufacture records for Deckdisc artists. I thought it would be easy, and if I had known how complicated it was, I wouldn’t have embarked on this journey. The vinyl movement in 2009, even abroad, wasn’t big yet. Everyone thought vinyl was a niche thing, for collectors or DJs. They were all wrong.

Are all Polysom records cut in-house?

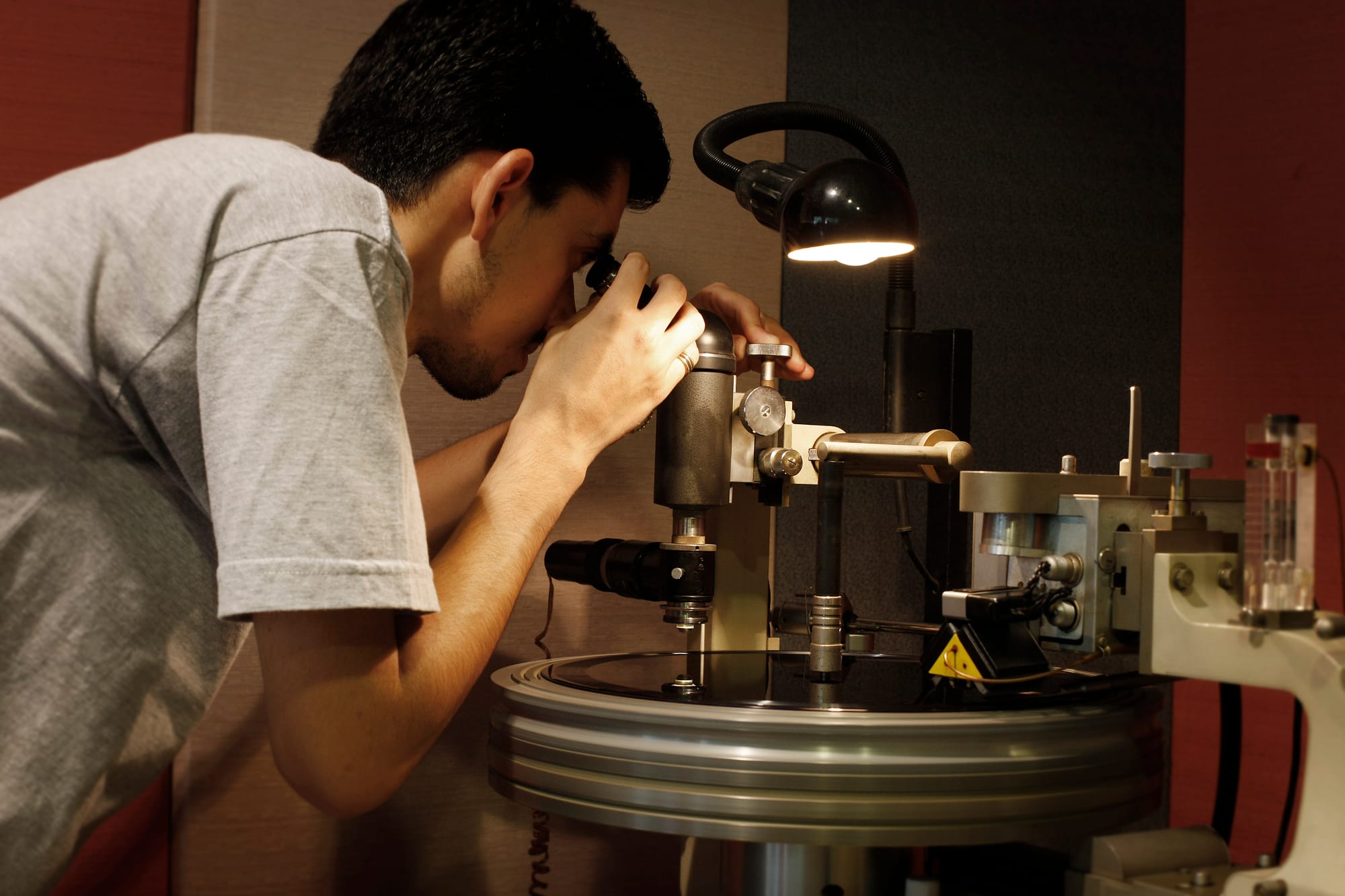

Yes, we have two Neumann lacquer-cutting machines and our results are admired worldwide.

In 2010, Polysom began reissuing MPB records from the 1960s and 1970s under the Clássicos Em Vinil series. How did this start?

The series began because we needed strong titles that would appeal to the public, and we leveraged our relationships with major record labels and publishers to secure the licenses. The major labels provided licensing support. Polysom carried out the project alone, without any other support.

Everyone was happy: We were happy because we had a high quality catalog, and [labels] were happy because they could move their catalog without worrying about manufacturing, inventory, sales, etc. Furthermore, Polysom recovered masters that were becoming damaged in the warehouses.

Was there a renewed interest in MPB in Brazil and the region prior to the series’ launch?

MPB is my specialty and that of Rafael Ramos, my son and partner at Deckdisc, who knows music like few others. He's the curator of the titles we release. There was little interest in these standards because they weren’t available in physical media and platforms like Spotify didn’t exist yet. I dare say that the Clássicos Em Vinil series has revived the great Brazilian music that was previously inaccessible in the people’s imagination.

Rafael is the curator, and he has the perfect network to assess the potential of new releases. The music released on Clássicos Em Vinil is ingrained in our blood.

How often are these artists involved in the reissue process, be it through approval or supervision of the release?

They have rarely been involved. Some are more cautious and need answers to their questions. Because of this, they are happy and fulfilled to see their music immortalized on vinyl.

The Clássicos Em Vinil series is especially popular outside of South America, helped by distribution via labels like Mr Bongo and Light in the Attic. What are the limitations behind exporting these records?

There are other distributors too. We were approached as soon as we released our music because Brazilian music is exceptional. Exporting vinyl is relatively easy because it’s tax-free in Brazil. What’s expensive are the shipping costs and, depending on the time of year, the exchange rate for euro and dollar.

Another big surprise, but one with a strong justification: Covid was the period in which we sold the most licensed records. Manufacturing [for other records] fell and only returned after the pandemic, when we reduced releases to prioritize independent labels and artists.

How often are master tapes used for these reissues?

For the Clássicos Em Vinil series, we only use the original tapes. All of them—regardless of the source—are mastered by our engineer Ricardo Garcia, a sound genius. Sometimes they are harder to find, but we usually manage to get them.

Is there a remastering process involved for these albums? Is the remastering done digitally or analog?

At that time, the audio tracks were finalized and mixed in the studio and sent directly to the lacquer cutting rooms, where no mastering was done—at most, stereo compressors were used. So nowadays, it’s necessary to master the albums from the original audio tracks to update the sound.

Mastering is done [by Garcia] using the original audio through analog-to-high-definition digital conversion.

[Writer’s note: While there’s no existing documentation we could find to explicitly support Augusto’s statement, it must be said that many of these albums were recorded under a repressive regime and, consequently, accomplished with tiny budgets. Tropicália artists saw the studio as fertile ground for experimentation, developing techniques on the fly to replicate some of the headier sounds they heard on Western psychedelic records. These were not friendly with the modest studio equipment they worked with.

In an interview by Brazilian journalist Ana de Oliveira, Manoel Barenbein—whose production work spans several albums under the Clássicos Em Vinil series by Costa and Os Mutantes, along with the 1968 album Tropicália ou Panis et Circencis, often cited as the groundbreaking manifesto for the movement—recalled that even distortion pedals would cause an issue in the studio. “The technicians wanted to kill me because they were the ones who adjusted everything, everyday, making sure that nothing would come out distorted,” he said. Artists under active persecution, he added, also made do with makeshift studios under terribly short timelines to avoid harassment by the police. Taking all of this into account, it’s reasonable to assume that fidelity was not on the minds of these artists, and that a proper mastering stage was not factored in.]

Have there been titles pitched for Clássicos Em Vinil that have not materialized for one reason or another?

When we don’t release something, it’s for legal reasons or due to a lack of [available] resources, such as album art or audio. But we work very hard to resolve everything.

There are Clássicos Em Vinil reissues that have been re-pressed over the years. How does Polysom decide which titles to reprint after the first reissue?

Of course. The vast majority of Clássicos Em Vinil are sold in large quantities, and the quantity of the initial pressing is always below what they could be sold.

There are also titles—like Milton Nascimento and Lo Borges’ Club de Esquina and Nelson Angelo E Joyce’s 1972 self-titled album—that have since been long out of print after being reissued. Are there plans to repress these titles in coming years?

Clube da Esquina is not being re-released because there are still unresolved legal issues by the record label. The brilliant Nelson Angelo E Joyce is among a list of titles that are in line for re-release. Our demand is greater than our manufacturing capacity.

The frequency of Clássicos Em Vinil releases has noticeably slowed down in recent years. Is there a reason for this?

The decline occurred much later. As I said above, in the post-Covid period, we had to forgo reissues to cater to independent labels and artists, who depended on them to continue their projects and ensure their survival.

What future plans are in store for Polysom?

Expand manufacturing, constantly improve quality, and try to lower costs and prices. As I said, Polysom is not a record label, and its distribution is adjusted for its size and capacity. The international market is already being served to the best of our ability.