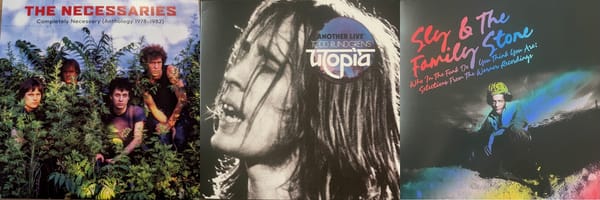

Reviews: David Bowie | Tower of Power

We checked out the new half-speed master of Station to Station and the Rhino Reserve pressing of Back to Oakland.

Today’s newsletter contains reviews for a pair of recent reissues—one for an undisputed classic and one for a record that, relatively speaking, may have fallen by the wayside in the ensuing decades. It wasn’t intentional to stick two reviews of ’70s albums together like this, but I think it worked out all right.

- David Bowie: Station to Station [50th anniversary half-speed master]

- Tower of Power: Back to Oakland [Rhino Reserve]

Station to Station’s 50th anniversary has me thinking about what other 1976 albums are going to get 50th-anniversary reissues in 2026. We already got the Vinylphyle edition of Frampton Comes Alive!—could we see potentially a special reissue of the Ramones’ debut, or Boston’s, or the Modern Lovers’, or Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’? Surely we’ll get something for Songs in the Key of Life’s 50th, yeah?

Feel free to shoot us an email at vinylcutnews@gmail.com and let us know which 50th-anniversary reissue you’d most like to see this year. We’ll post the results in a future newsletter. Oh, and speaking of future newsletters, you can ensure that there will be plenty of those going forward by upgrading to our paid tier! (See how I snuck that in?) You’ll support our writing directly and get all our paid-subscriber perks, including eligibility for our monthly vinyl giveaways. Get to upgrading by clicking right here.

And hey, you know what album could really use a 50th-anniversary reissue in 2026? Yep, we said it.

On to the reviews.

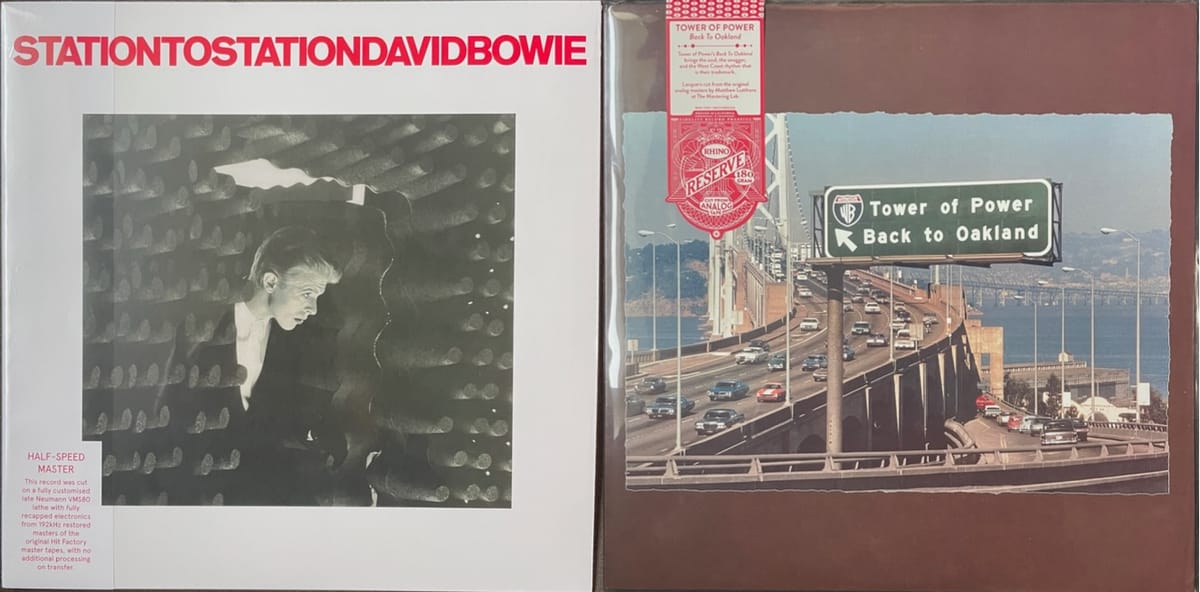

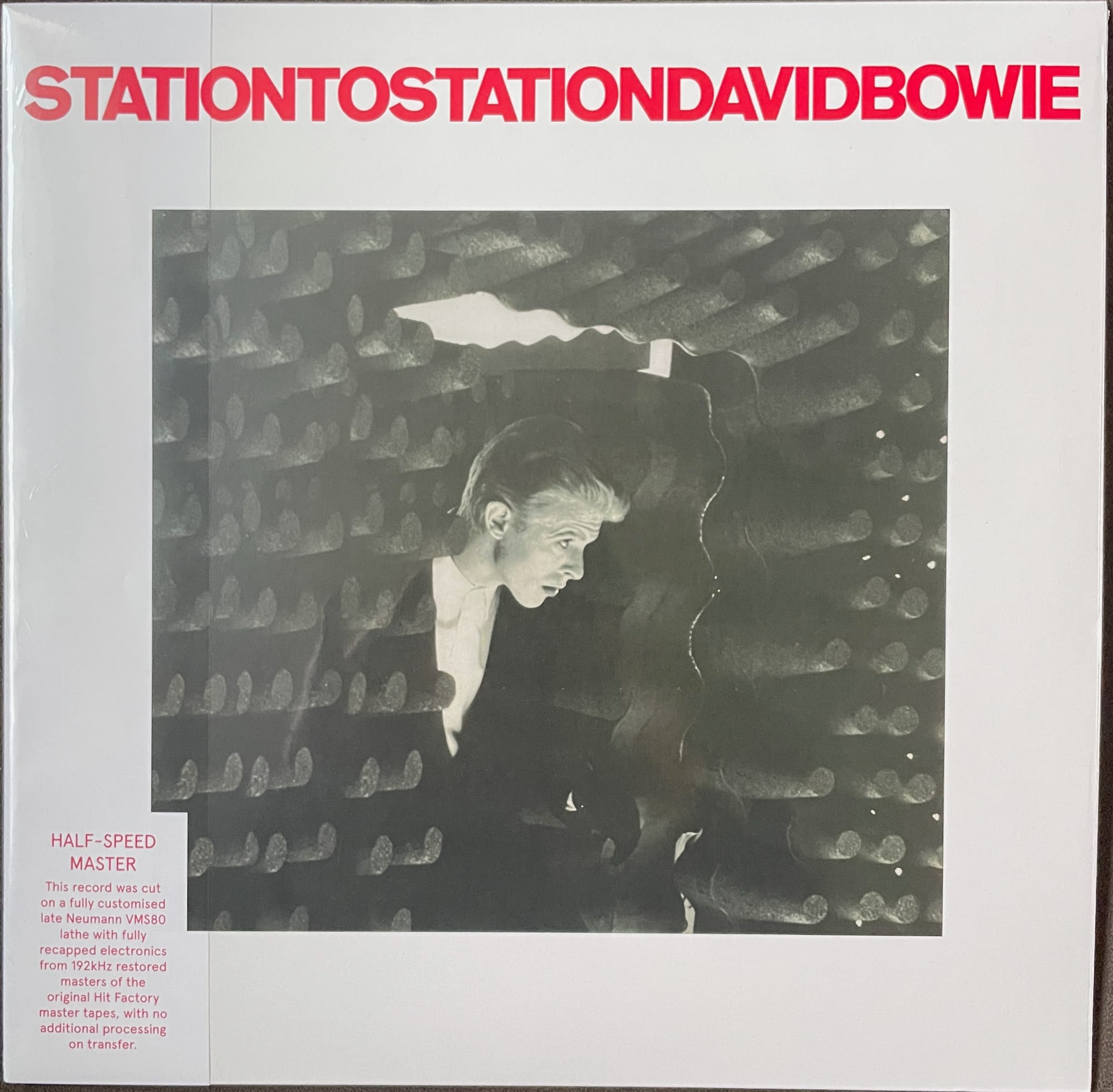

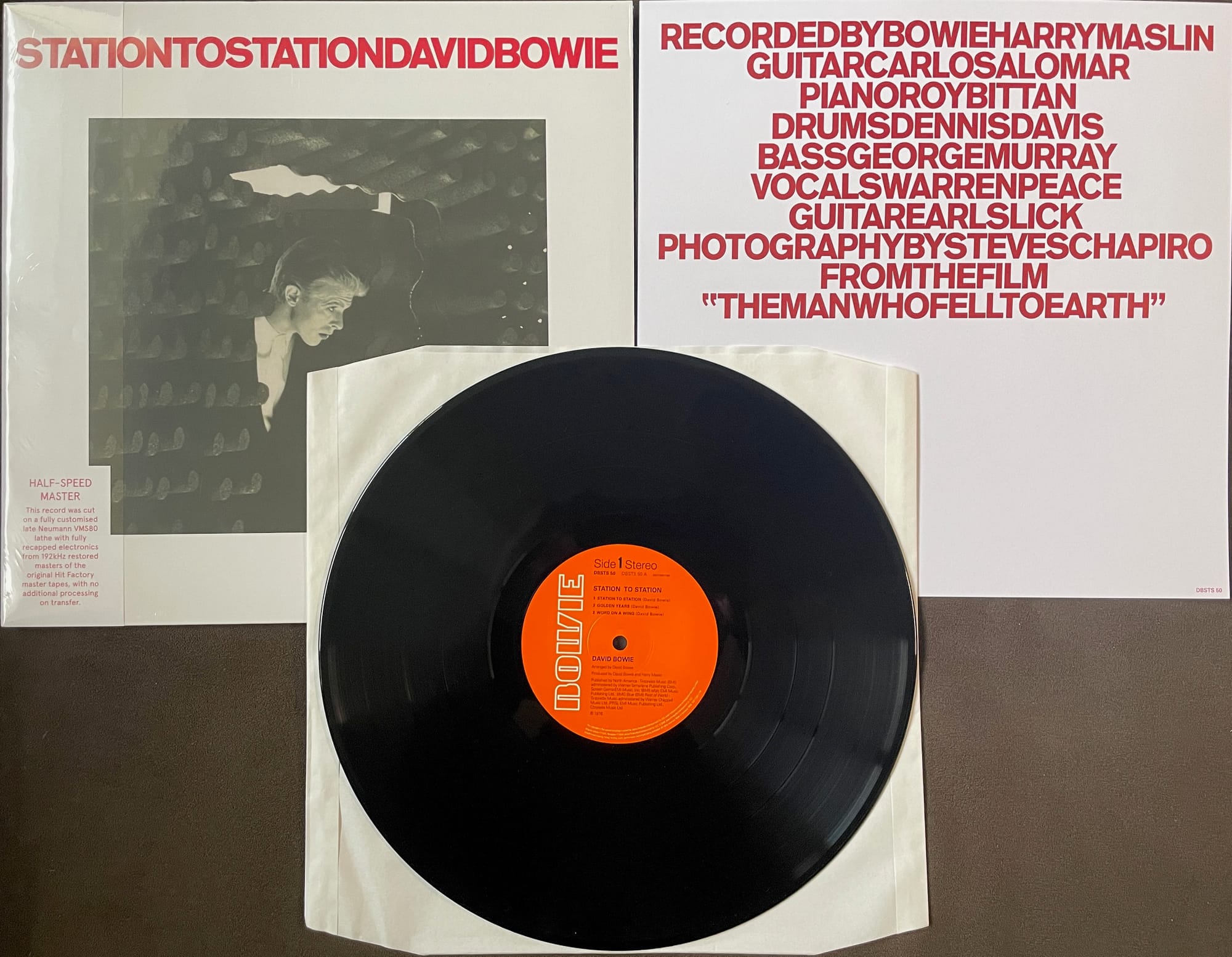

David Bowie: Station to Station

As each album in David Bowie’s discography hits the half-century mark, Parlophone has released a half-speed-mastered vinyl edition to commemorate the occasion. It being 2026, it’s now Station to Station’s turn. (A 50th-anniversary picture disc has also been released, but we won’t be talking about that today.) The album was recorded in 1975 at Los Angeles’s recently opened Cherokee Studios, which had just taken over MGM Records’ former recording facility a few months prior, and was mixed in New York at the Hit Factory in November of that year. It documents Bowie at a breaking point, suffering from paranoid delusions while under the influence of cocaine and occultism.

And it’s a masterpiece, only damned by the fact that Bowie made so many dang masterpieces during the 1970s, so it’s a little tough for this one to stick out. Station to Station might be the most difficult, most snarled one—but even that is a simplification, as it is a readily accessible album, especially by Bowie’s standards.

Let’s start with the singles: “Golden Years” and “TVC 15” are seemingly straightforward pop confections that turn out to be dense and roiling beneath their surfaces. The former is a direct follow-up to Bowie’s surprise smash “Fame” and continues his fascination with American R&B, while the latter is disguised as a ’50s-style rock ’n’ roll number. Both explode their parameters to become something more arty, more garish, and infinitely more complicated.

Elsewhere, “Word on a Wing” is a gospel song rooted in utter despair, with a stream-of-consciousness structure that incorporates Bowie’s most outright religious lyrics. “Stay” is a wicked funk chugger that is perhaps the album’s most conventional track, while “Wild Is the Wind” is probably its most universally appealing segment. It’s categorically one of Bowie’s crowning achievements: an almost shockingly heartfelt cover of the Dimitri Tiomkin/Ned Washington song by way of Nina Simone’s interpretation that could well contain Bowie’s greatest vocal performance.

That leaves the title track, a two-part, 10-minute suite that still confounds Bowie scholars to this day. I hesitate to pick at it too much, especially lyrically—the writings of Chris O’Leary and Nicholas Pegg offer much better critical explorations than I ever could—but it is a quite literal manifestation of Bowie’s fragmented psyche during his time in LA. This was reportedly the darkest period in his life, with the singer living on a diet of red and green peppers, milk, and cocaine and his weight nearly down to a shocking 80 pounds. Bowie was in the throes of paranoia and totally infatuated with symbology and mysticism; “Station to Station” alludes to both the Stations of the Cross and the Ten Sephirot of the Kabbalah (Kether and Malkuth are specifically name-dropped)—although the line that registers most clearly is “It’s not the side effects of the cocaine; I’m thinking that it must be love,” with Bowie not really convincing the listener or himself that coke has nothing to do with whatever’s going on here.

Musically, the track is one of Bowie’s most complex; the first half slowly emerges out of a synthesized train —inspired by the car sounds in Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn”—into a near-plodding march shrouded in ghostly feedback. It’s all driven by Dennis Davis’s drums and circular guitar lines from Earl Slick and Carlos Alomar. The second half shakes off the gloom and becomes something surprisingly upbeat, with even a hint of disco bounce; a repeat of the “Thin White Duke” refrain ties the two sections together. The arrangement deconstructs the typical roles of rock-ensemble instruments and recasts them, pointing the way forward to the work Bowie would embark on with 1977’s Low. It’s disconcerting and seductive in equal measures, as it rewires the format of a rock song much in the way the progressive rock bands of the era were used to doing, and yet it sounds like nothing else in existence. Chris O’Leary writes, “It’s his masterpiece, for better or worse,” and while I’m not sure I think it’s Bowie’s best song, I do believe it’s the one that you could listen to the most without ever fully getting to the bottom of.

Station to Station’s new half-speed pressing has strengths and weaknesses. Like all current-day half-speed-mastered vinyl, it was cut from digital, in this case by John Webber at AIR Studios from 192kHz transfers of the master tapes. Half-speed mastering seems to be the gold-medal treatment at British mastering studios these days, while we Yanks tend to prefer tape-to-lathe analog cuts. The half-speed process certainly has its champions, though, who tout the clarity, stability, and enhanced bass and treble extension it imparts to the vinyl. The process has its detractors, too, who decry the way it can potentially alter the properties of the original recording; analog purists also bemoan its over-reliance on digital sources.

As for this particular half-speed mastering, there is measurably increased low end, resulting in a more forceful sonic picture; this carries over to Davis’s drums and George Murray’s nimble, unassuming bass. It works well in a song like “Stay,” which relies on rhythmic excitement to get its point across, but it’s less effective on “Wild Is the Wind,” which feels needlessly aggressive. The worst point comes at the start, during the first half of “Station to Station.” The new cut makes this section sound vacuum-sealed, with all of the air sucked out of it. On first play, I wondered if I was coming down with a head cold. Fortunately, the second half of the track opens up substantially.

Elsewhere, I noticed some added definition to various elements in the mix, allowing my ear to pull out sounds and voicings I had not been able to differentiate on my many previous listens to Station to Station. That made for a super-interesting experience, but that also led me to having the disorienting sensation that the mixes were strangely out of whack; all of sudden I felt like I could hear miscued phrases, guitar fluffs, and vocal goofs that had previously blended into the background. Obviously much of this is my own biased perception, as this is not a new mix, but the carefully balanced sonic picture now sounded skewed to me, as if the sonic colors had been shifted.

I compared the new half-speed to my 1976 US pressing, cut by Allan Zentz at RCA and pressed at RCA’s Hollywood plant. This is an incredible-sounding record, with plenty of range, separation, and low-end thump. There’s a snap and crispness that keeps the recording full of life and energy, and if there’s occasionally a bit of edginess on some of the highs (most noticeable to me during the second half of “Station to Station”), the majority of the album sounds absolutely fab. I also have the 1991 Rykodisc CD firmly imprinted in my brain, and the sonic signature of that is so different from the Zentz cut that I don’t think that simply a different mastering approach can account for my response to the new half-speed cut.

I also referred to a 1986 black-label reissue pressed at RCA Indianapolis with no lacquer cutter credited, and the digitally sourced pressing included the Who Can I Be Now? (1974–1976) box set from 2016, also with no lacquer cutting engineer credited. The ’86 has the Zentz’s elasticity and air but loses some of the resolution and low-end information, resulting in a slightly boxier and more distant sound. And the 2016 version—likely made from the same digital transfer that this new half-speed master was cut from—is quite transparent and detailed, but the overall sonic picture is muted, with a smaller soundstage and a constricted dynamic range. However, it is easier on the ear long-term than the new half-speed, which I found to be very slightly fatiguing. That said, I believe the half-speed offers some of its own advantages in terms of bass resonance and instrument separation; it may be a more successful choice for certain systems that rely on records cut with extra punch to sound their best.

The half-speed’s Optimal pressing was flawless in my case (the 2016 cut is also from Optimal). It’s so well done that it’s absolutely a selling point; my older RCA cuts have minor age-related issues, and my 2016 had some pressing flaws in the form of ticks and clicks. The packaging is pretty straightforward, with a sheet of paper slotted in the jacket with the musician credits that were included in the US original’s paper inner sleeve.

I’ve listened to Station to Station so much recently that I have witnessed the album shape-shift before my ears. On one listen, it’s an intelligent bit of mainstream, soul-inflected pop-rock—the capable follow-up to 1975’s Young Americans, the album that made Bowie a huge success in America for the first time. On another, it’s Bowie’s clear signaling of the future experimentalism of Low, Heroes, and Lodger, with ambivalence toward existing rock and pop conventions. On yet another, it sounds like the product of a clearly disordered person, one who was so addled that he later said he couldn’t even remember making it. And then on others, it’s a fully assured, confident, and dramatic statement from an exceptionally gifted artist in full control of his powers. That indefinable, mercurial quality is true of this new half-speed master, too. Parts of it draw me in and offer sonic fascination, while others treat my ear roughly and push me away. I can’t quite make heads or tails of it, and in that way it encapsulates everything that makes Station to Station so perplexing and beguiling.

Parlophone 1-LP 33 RPM 180g black vinyl

• 50th anniversary half-speed master of David Bowie’s 1976 album

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single pocket

• Inner sleeve: White poly-lined

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: Single-sided insert replicating original album inner

• Source: Digital; “This record was cut on a fully customised late Neumann VMS80 lathe with fully recapped electronics from 192kHz restored masters of the original Hit Factory master tapes, with no additional processing on transfer.”

• Mastering credit: None

• Lacquer cut by: John Webber at AIR Mastering, London, UK; “JWM in deadwax”

• Pressed at: Optimal Media, Germany

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: A fold-around obi strip covers the spine, in the manner of Rhino High Fidelity or Vinylphyle releases. A 50th anniversary Station to Station picture disc is also available.

Listening equipment:

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980

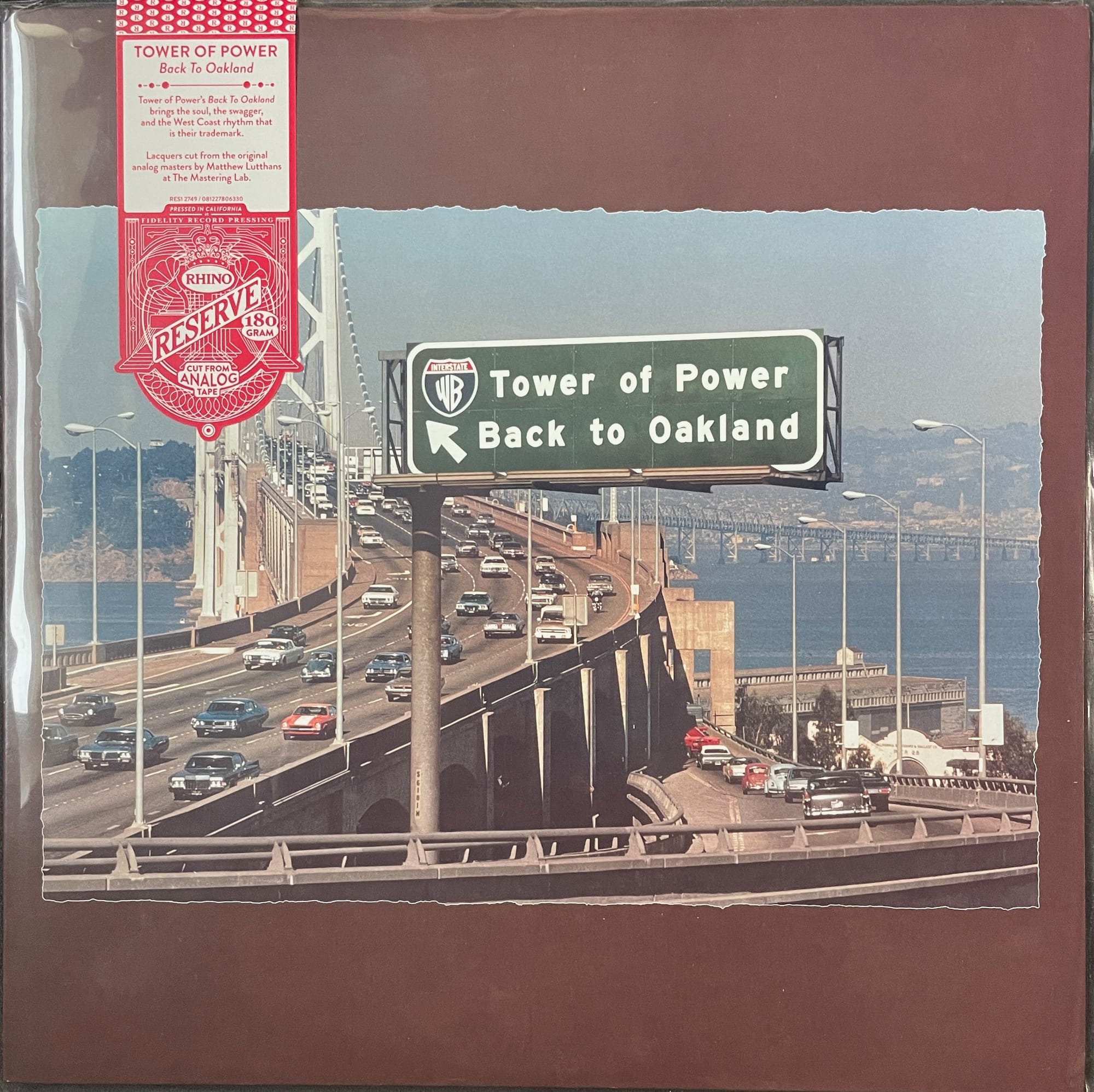

Tower of Power: Back to Oakland

Tower of Power’s peak on wax is easy to pinpoint: It’s when the band released their 1973 self-titled breakthrough and its follow-up, 1974’s Back to Oakland, on Warner Bros. Records. That period saw Tower of Power reach their greatest chart success, but perhaps more significantly, it was also the only time the band’s lineup included three crucial members—lead singer Lenny Williams, keyboardist Chester Thompson, and drummer David Garibaldi, each of whom elevated the group’s funk-laden R&B to commercial and virtuosic heights. Back to Oakland, the slightly lesser-known album of the pair, has been reissued on the Rhino Reserve imprint with an all-analog cut from the master tape done by Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab. It’s a chance to revisit a band that was hugely influential in the ’70s and early ’80s—the “Tower of Power Horn Section” was featured on so many albums that it became a brand unto itself—but whose songs have perhaps not endured in the cultural consciousness the way those of Earth, Wind & Fire or Kool and the Gang have.

Title aside, Back to Oakland displays plenty of Oakland pride, from the cover photo of the Bay Bridge to the album’s brief instrumental bookends that are edited sections of a longer jam called “Oakland Stroke”—a show-offy bit of slice-and-dice rhythm that displays the band’s chops from the jump. Tower of Power’s brand of funk is not one of stank (à la Funkadelic) or second line (à la the Meters) or gritty repetition (à la James Brown) or even blissed-out psychedelia (Sly and the Family Stone, their neighbors from just across the Bay). Rather, theirs is one of precision and architecture, taking some of its cues from the jazz-rock movement of Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears but dispensing with the rock part of the equation in favor of R&B, as embodied in the genre’s dual forms: soul-stomping gitdown and luscious heartbreaking balladry. Tower of Power also subtly called back to the big-band era, as the 11-piece band offered a broader, more detailed, and more synchronized sound than most R&B and jazz outfits were delivering at the time.

The album is evenly split between astonishingly taut funk workouts and sumptuous torch songs. The instrumental tour de force is the Thompson-composed “Squib Cakes,” which follows the jazz format of head/solos/head but transposes it to a wickedly tight funk interface. Thompson’s solo, making full use of the bass pedals on his organ, has him fully locked in with the ensemble, evidence that the Tower of Power rhythm section had just as much cause for renown as their vaunted horns. On the flipside, “Below Us, All the City Lights” is an orchestra-augmented ballad that swells Tower of Power’s already substantial sound to rococo proportions. It’s their take on the Philly sound of the era, cut through with a big-screen Hollywood sentimentality—it’s almost comically over-the-top.

I did not have an original pressing of Back to Oakland to compare the Rhino Reserve to, but I did listen closely to my 1973 pressing of the self-titled album for reference. That may sound like apples and oranges, but I wanted to get a sense of what Tower of Power sounded like on vinyl to their contemporary audience. My Santa Maria pressing of Tower of Power has surprising depth and punch, and the band’s quick rhythmic attack on songs like “What Is Hip?” is fully articulated. However, the overall sound image is one of integration and blending, with the bass trimmed back, the horns woven together in a unified timbre, and the drums unfortunately sounding like part of the backdrop rather than the driving engine, with most of the sonic spotlight being devoted to Williams’ vocal.

The new Rhino Reserve cut doesn’t merely have more definition and width, but also the bass is deeper while simultaneously sounding more resonant and natural. The individual horns can be differentiated, and there’s a tiny little sparkle, a shiny glint on the mid-highs that makes the album really involving and pleasurable for the ears. Best of all, the drums are fully transparent, with Garibaldi’s stickwork leaping out in stunning focus. You can hear him bouncing from hi-hat to snare to tom-tom without there being any question of where his hands and feet are at any given moment. That enhanced aural visibility may be down to the production choices on Back to Oakland, but considering it was a more ambitious album with a larger sonic tapestry that included guest strings, backing vocals, and even more horns, the level of detail that Lutthans was able to maintain is attention-getting.

The excellent, warmly detailed mastering is helped by the close-to-perfect pressing from MoFi’s Fidelity Record Pressing—now par for the course with the Rhino Reserves. With a virtually silent background to the vinyl, all of the album’s intricacies can be heard, from the horns’ subtle chord shading to the interplay between Garibaldi and conga player Brent Byars. Bruce Conte’s guitar cuts through with an enjoyable crispness here that I have not noticed before on other Tower of Power records, where he seems to be somewhat buried. And the LP features a pair of the band’s best-written tracks: the album’s single, “Don’t Change Horses (in the Middle of a Stream),” and the Hi Records–indebted “Man from the Past,” both of which show Lenny Williams acting as capable ringmaster to Tower of Power’s three-ring sound. Back to Oakland may find Tower of Power eager to show off their hometown pride, but it’s also the sound of the band making their bid as a world-class talent, and succeeding.

Rhino Reserve 1-LP 33 RPM 180g black vinyl

• New all-analog mastering of Tower of Power’s 1974 album

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single pocket

• Inner sleeve: Fidelity Record Pressing–branded poly

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: None

• Source: Analog; “Lacquers cut from the original analog masters”

• Mastering credit: Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, Salina, KS

• Lacquer cut by: Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, Salina, KS; “MCL” in the deadwax

• Pressed at: Fidelity Record Pressing, Oxnard, CA

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: Comes inside a reusable poly sleeve sealed by a hype sticker, as per other Rhino Reserve titles.

Listening equipment:

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980