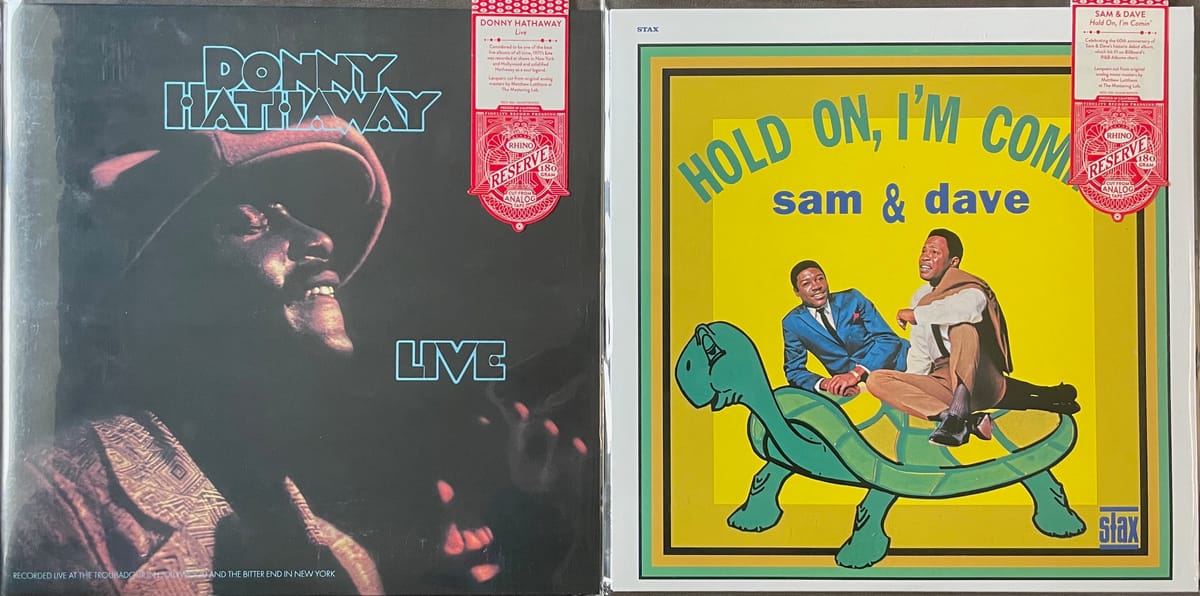

Reviews: Donny Hathaway | Sam & Dave

New Rhino Reserve pressings of Donny Hathaway’s 1972 Live album and Sam & Dave’s 1966 debut full-length.

Today we’ve got reviews of the two remaining soul albums Rhino Reserve has reissued at part of Black History Month. (If you missed our reviews of Otis Redding’s Pain in My Heart and The Soul Album, click here.) One’s a stirring live album originally released on Atco that’s still widely imitated to this day, and the other is the 1966 Stax debut album from the dynamic duo that came to define the Memphis label’s sound in the ’60s.

- Donny Hathaway: Live

- Sam & Dave: Hold On, I’m Comin’

But first...

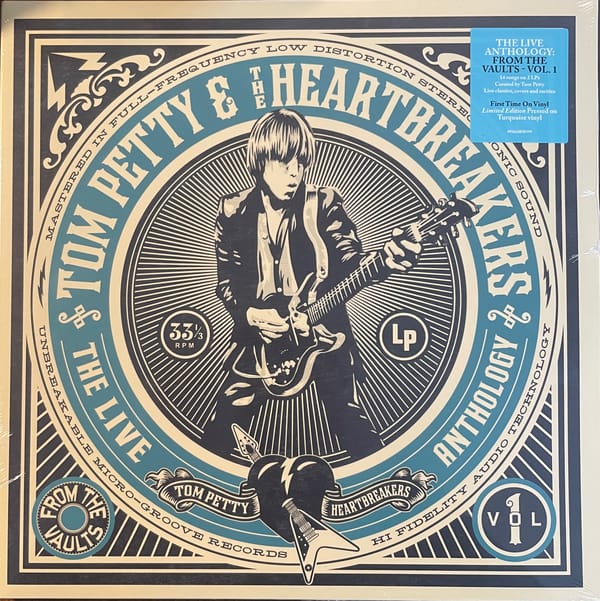

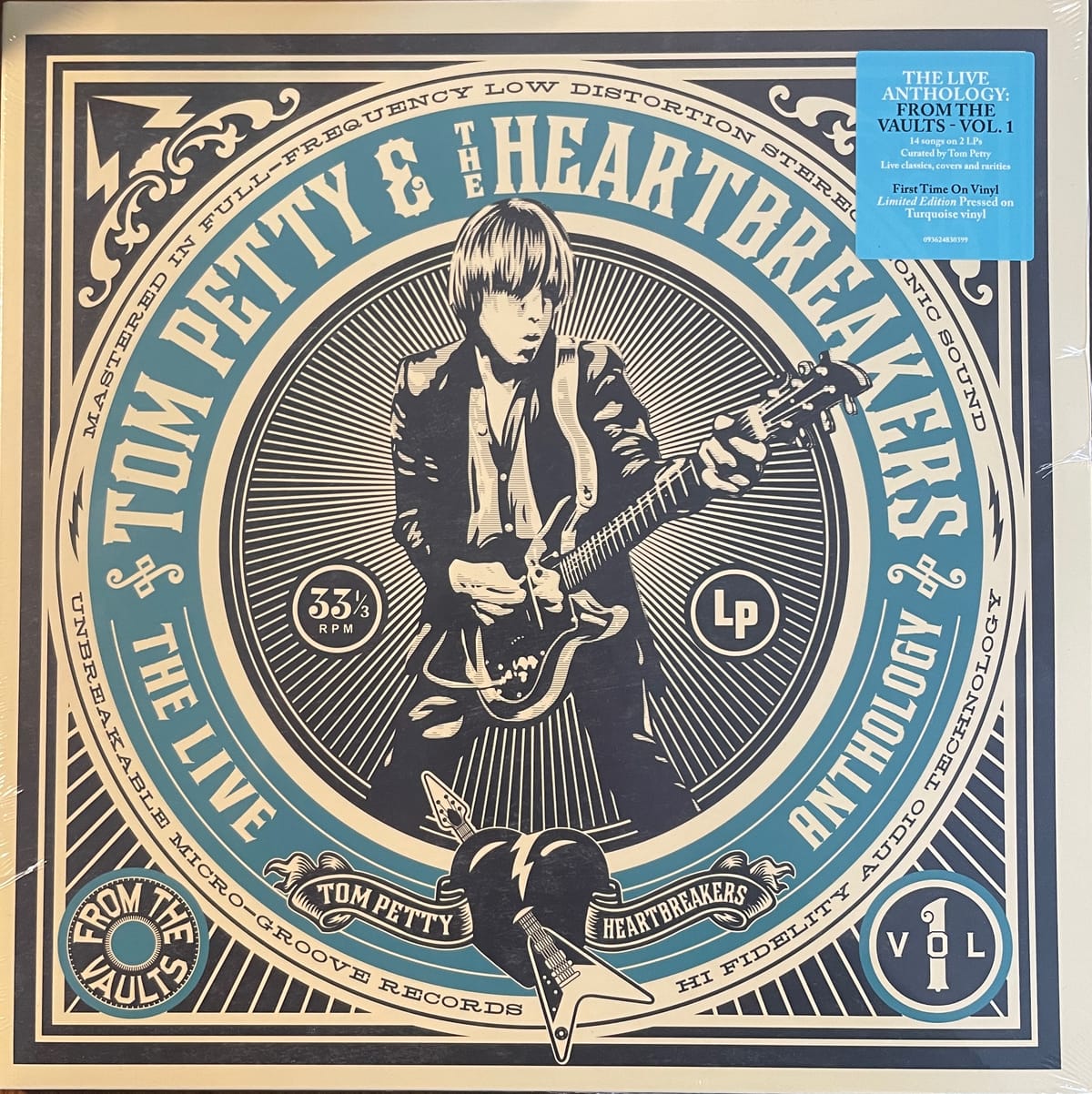

Our February vinyl giveaway is now live! We’re giving away a copy of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ The Live Anthology: From the Vaults - Vol. 1, a limited-edition double LP that was released in November as part of Record Store Day’s Black Friday. Copies are scarce now, so click on the rectangle above to enter to win. You’ll need to be a member of our paid subscription tier, but upgrading is easy and fun—and it helps support our writing here at The Vinyl Cut, so it also makes you a cool and wonderful person.

We’re deeply grateful to our paid subscribers, whose ongoing support allows this site to exist in the first place. Be like them! And support independent writers who treat vinyl with the care and obsession that you do.

On with the show.

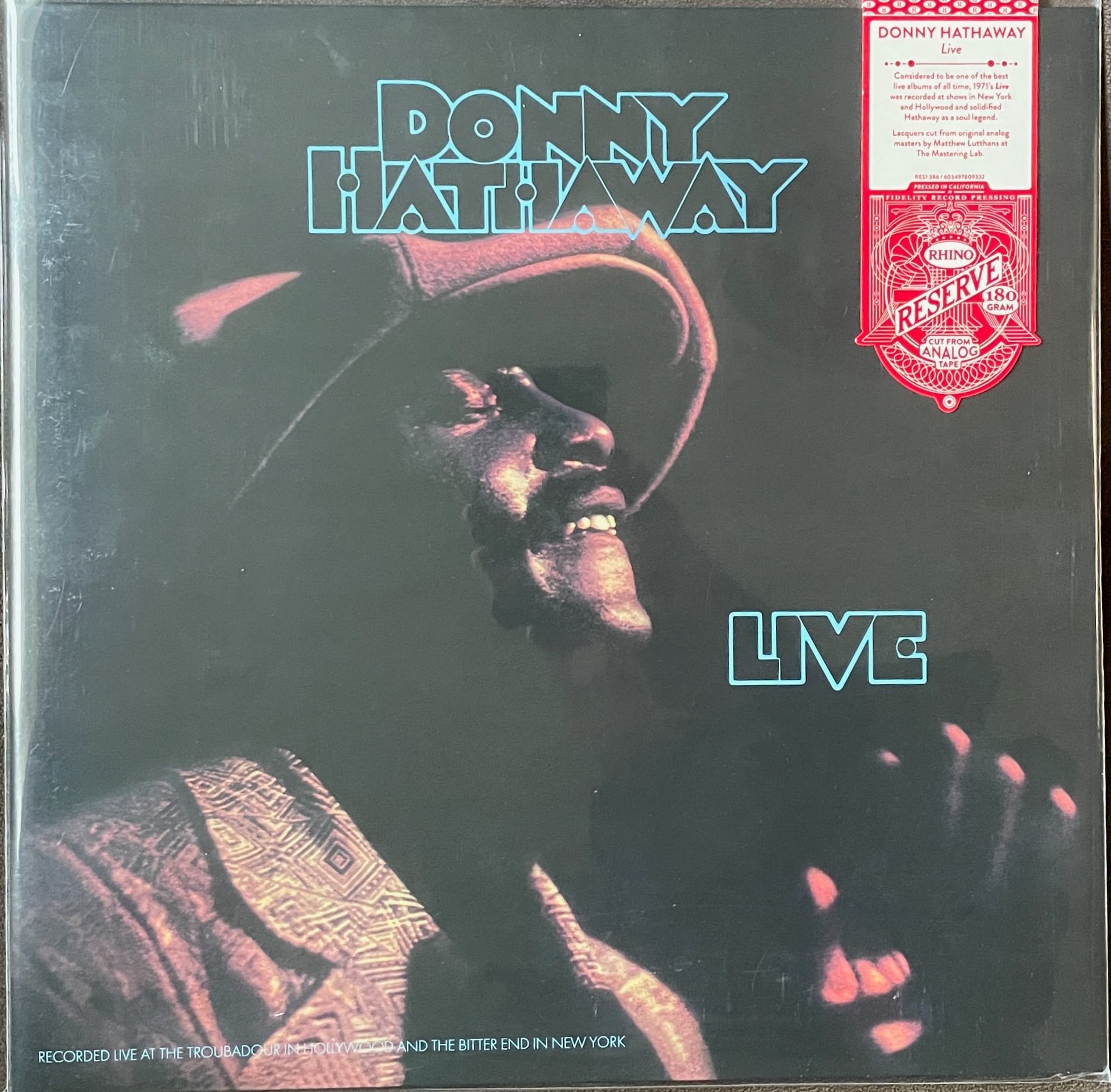

Donny Hathaway: Live

Any hint of the tragedy that accompanied the short life of Donny Hathaway is nowhere to be heard on Live, the 1972 album that has become the best encapsulation of the singer/keyboardist’s legacy. The album remains a hit of pure, uncut joy, with Hathaway leading a crack band in front of intimate audiences at the Troubadour in Los Angeles and the Bitter End in New York City. It’s a singularly rapturous experience, one of the few live albums that captures the emotional thrill of a transcendent live performance. You can hear the crowds squeal in ecstasy throughout the disc, and the music sounds so good that you’re right there with them.

Hathaway’s lightly smoky singing voice was a pliant, elastic instrument that felt like it was wired directly to his heart, making such an impactful sound that no less than Stevie Wonder—already one of the most accomplished singers of the day—spent a couple of his prime years trying to imitate him. But it’s the ensemble performing on Live, led by Hathaway’s electric piano, that sends the recording to the next level. Bassist Willie Weeks is the standout, offering a no-nonsense harmonic foundation, but drummer Fred White, who would later go on to join his brother Maurice in Earth, Wind & Fire, keeps the grooves on lockdown, always pushing the momentum forward without ever rushing. The band’s playing is fleet of foot but never busy, and the musicians pivot exquisitely within their blend of soul, jazz, funk, and gospel.

Highlights include “The Ghetto,” the 12-minute centerpiece of Side 1, which features solos from Hathaway and conga player Earl DeRouen. Despite the loose, improvisatory structure, the song erases any negative connotations of the word “jam.” This is a collective of musicians listening to each other, letting the music evolve into cycles of tension and release, making the audience as much a part of the performance as the notes played. And Hathaway’s live version of that overly familiar greeting-card ballad “You’ve Got a Friend” completely redeems the glib torpor of the James Taylor version, turning Carole King’s tune into a revival-meeting sing-along that is chill-inducing no matter how many times you’ve heard it. The sounds, grooves, and flows featured on Live have been imitated by literally thousands of bands, but they have never been bettered.

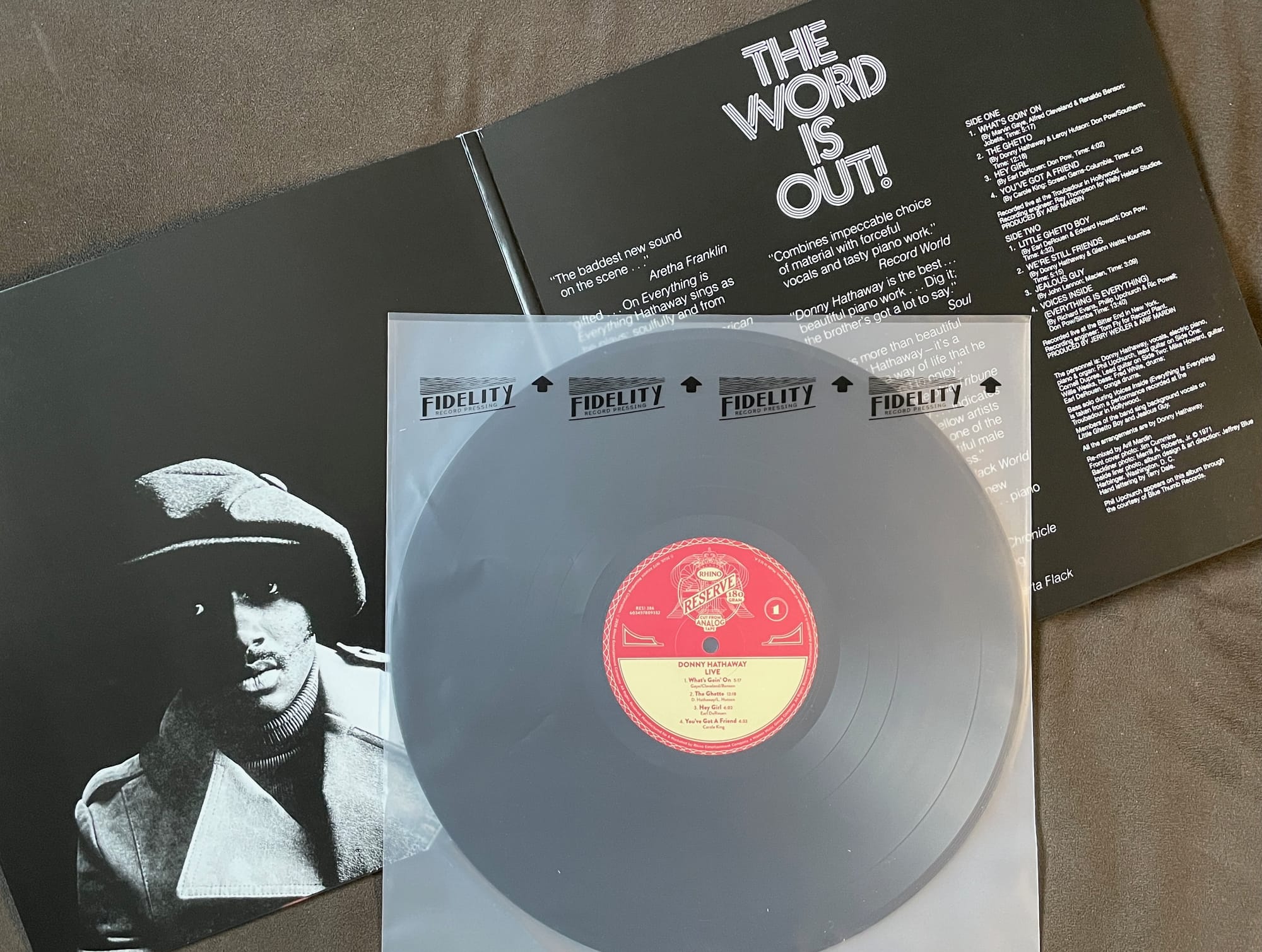

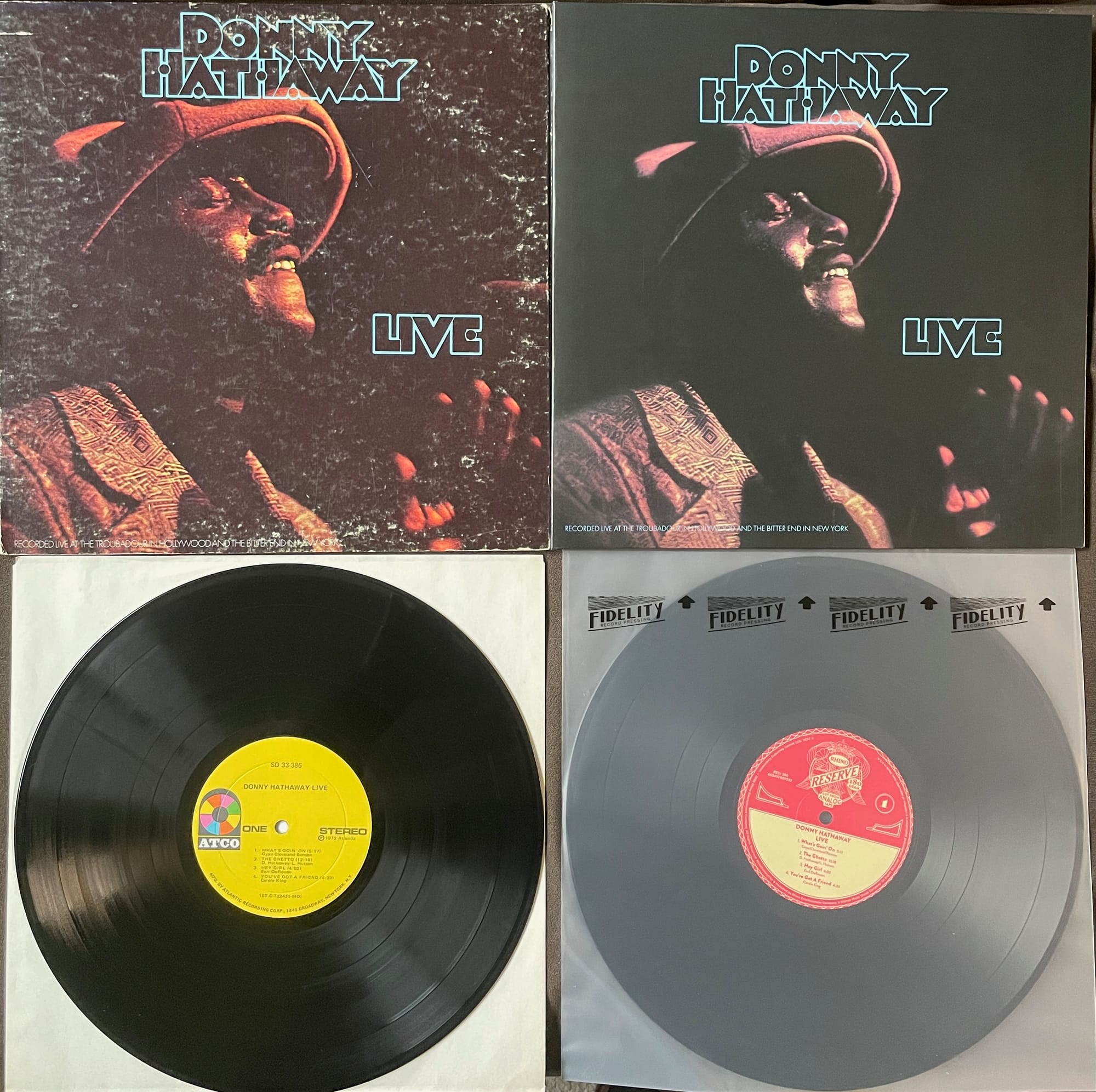

The Rhino Reserve edition is taken from the analog master tape, and it sounds warm, wise, and wonderful. I compared it to my 1972 Monarch pressing, a George Piros cut made at Atlantic Studios in New York that is a phenomenal-sounding record in its own right—all the more so because of its incredibly lengthy sides, which are more than 26 minutes each. The 1972 cut has significantly more top end, offering some additional visibility into the ensemble’s overall texture while also injecting a level of toppy excitement. However, the sound occasionally becomes clustered on my (admittedly bright) system, and even breaks up for split-seconds during the cymbal crashes toward the ends of the sides. The sonic blend occasionally becomes dense, murky, and even, once in a while, shrill; the audience screams don’t help. Piros is one of my favorite mastering engineers, and I love the sound of his work. But there was more to wring out of this record, apparently.

The new pressing, cut by Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, betrays no evidence of having longer-than-usual sides, except the disc is cut at a lower level, which is not a problem due to the silent background of the Fidelity-pressed vinyl. (My copy was measurably dished, perhaps the only major pressing issue I’ve ever encountered from a Rhino Reserve.) The album gatefold is reproduced nicely, with a slightly cooler tone and a different crop than the original, showing a bit more of the image.

Sonically, the different instruments are better integrated on the Lutthans cut, and the sound of the audience—a significant element to this recording—does not sound like accidental ambience that happened to be caught on tape, as it occasionally does in the 1972 cut. Here, they are fully integrated into the music, and the end result is that you feel like you’re present at the gig, standing in the audience with the band in front of you. I realize that “you are there” is a cliché, but I’m not embarrassed to use it in this case. You can hear not just the dimensions of the room but the sweat on its walls and the steam moving through the space. The tone of Hathaway’s electric piano has an inviting glow, and White’s drums snap and thump in all the right ways, while Weeks’s bass is more clearly articulated and positioned than in the OG. I suppose individual results may vary—some might wish for the audience to be pushed back rather than emphasized—but I preferred the Reserve’s more full-throated, more immersive, and balmier sound to the edgier version that’s on the Piros.

Donny Hathaway’s Live has always been a generously upbeat and compulsively playable album, one that’s suitable for all kinds of situations. That makes it all the more crucial for an excellent-sounding version of it to be available to any and all vinyl enthusiasts, and this new Rhino Reserve pressing more than fits the bill. It does more than reinvigorate a well-established classic—it makes it sound more alive than ever, making yet another convincing case for it as one of the finest live albums of all time.

Rhino Reserve 1-LP 33 RPM 180g black vinyl

• Analog remaster of Donny Hathaway’s 1972 live album

• Jacket: Direct-to-board gatefold

• Inner sleeve: Fidelity Record Pressing–branded poly

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: None

• Source: Analog; “Lacquers cut from the original analog masters”

• Mastering credit: Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, Salina, KS

• Lacquer cut by: Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, Salina, KS; “MCL” in the deadwax

• Pressed at: Fidelity Record Pressing, Oxnard, CA

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): B (the disc was noticeably dished)

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: Comes inside a reusable poly outer sleeve sealed by a hype sticker, as per other Rhino Reserve titles.

Sam & Dave: Hold On, I’m Comin’

By the time of their debut album, Sam & Dave were already in command of one of the most exciting live shows of the ’60s. They had brought their energetic call-and-response vocal style from out of the church and into the nightclub, where that fusion of gospel and R&B electrified audiences. They were such dynamic performers that, after sharing a bill with them, Otis Redding once said, “They’re killing me. I’m going as fast as I can, but they’re still killing me. Goddam!” [Peter Guralnick, Sweet Soul Music, 1986.] So the primary challenge of putting Sam & Dave in the studio became a question of how to capture that live spark on record. It didn’t happen right away.

The duo of Sam Moore and Dave Prater had been performing together since teaming up in Miami in 1961, and their singing styles were informed not just by the gospel church but also by Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson, and James Brown. After they floundered with a few early singles on the Marlin and Roulette labels, Atlantic Records executive Jerry Wexler took an interest and stationed them with Stax Records, which was partnered with Atlantic at the time. Sam & Dave’s first two Memphis singles flopped, but the third, 1965’s “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” became a hit, and the fourth, “Hold On, I’m Comin’,” was a bona fide smash—leading to the 1966 album of the same name, their first full-length. Featuring the early songwriting of Isaac Hayes and David Porter, Hold On, I’m Comin’ gave the impression that Sam & Dave had arrived fully formed, like Athena from the head of Zeus. But of course this was the result of years of experience, and by this time Moore and Prater were both hovering around 30 years old.

The album is a soul revue par excellence, with some lean ’n’ mean backing by Hayes, Booker T. and the M.G.’s, and the Mar-Keys horn section. The album conveys the excitement of a live show, no doubt the result of the Stax modus operandi of recording live in the room. Moore’s high tenor was not the smooth instrument of, say, the Righteous Brothers’ Bobby Hatfield; it was a rough, raspy instrument designed to inflame audiences with excitement. Prater’s baritone/tenor had a rounder, slightly more mellifluous tone but was more than capable of some grit of its own. One of Sam & Dave’s hallmark qualities was the markedly even balance between the two singers, sharing lead on almost every song—a give and take that would eventually cause immense friction within the duo.

“Hold On, I’m Comin’” and “You Don’t Know Like I Know” are indelible soul classics at this point, but the entire album is consistent, featuring eight sweat-inducing potboilers, three heart-rending ballads, and the funkily midtempo “Don’t Make It So Hard on Me.” It’s a joy to hear Moore and Prater interacting with Stax’s perfectly sculpted horn lines, Steve Cropper’s brightly funky guitar, and Al Jackson Jr.’s authoritative drumming. The pair even take on some close-harmony singing—perhaps derived from the Everly Brothers, which would place Sam & Dave on a parallel path with Simon & Garfunkel, who were doing a similar thing at this time in New York within the folk-pop idiom.

Cut from the analog mono master tape by Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, the Rhino Reserve pressing is irresistible on a musical level, compelling any listener to shake a thing or two. For whatever reason, it is not the best-sounding Stax reissue I have heard lately (see our review of the two recent Otis Redding albums in the Rhino Reserve series). It sounds like the master tape simply may not have as much dynamic range as some other Stax records, with the bass rarely drawing attention to itself (the end of “You’ve Got It Made” is a notable exception) and the attack of certain instruments in the midrange occasionally swallowing up some of the competing elements. The two singers and certain instruments, while faithfully captured, sound slightly distant, a result of hasty production choices and the nature of the unconventional Stax recording studio. Perhaps this cut is simply an accurate representation of the sound of the album master—which would have been compiled from several sessions recorded over many months.

The consistent excellency of the Rhino Reserve titles, and of Lutthans’s work in particular, assures me that this is the very best representation of the album masters currently possible. I do not have a 1966 Stax original to compare, but I checked out the album’s three singles—“If You Got the Time,” “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” and “Hold On, I’m Comin’”—on my 1969 Monarch pressing of The Best of Sam & Dave (on Atlantic) as well as on the recent (and phenomenal) vinyl editions of The Complete Stax/Volt Singles 1959–1968. My Monarch Best of, which uses the stereo mixes, provided no worthwhile comparison, as the Reserve sounded better on every front. The Complete Stax/Volt comps were much more illuminating, and I wonder if the mono single masters they used—digitally transferred before mastering and cutting—could potentially be one generation closer to the session mixdowns than the versions used on the 1966 LP assembly reel. The Complete Stax/Volt versions offered more clarity to those three songs, allowing the ear to peer into the individual musical lines and dissect the arrangements. But it lacked the warmth and oomph of the new Lutthans tube cut, sounding a touch more clinical and brittle.

Hold On, I’m Comin’ was a sterling, fiery debut LP for Sam & Dave, but it also functioned as the formal announcement of the Hayes/Porter duo as a force to be reckoned with. The pair’s stars rose along with those of Moore and Prater, and the album’s strengths rely on the songwriters’ excellent pop-soul chops. But Sam & Dave deserve their full share of credit. The freshness of their act in subsequent years may have seemed diluted after being stolen part and parcel by the Blues Brothers, but the impact of their call-and-response vocals and their entwined dynamism and stage presence still carries striking power. Hold On, I’m Comin’ is where it all came from.

Rhino Reserve 1-LP 33 RPM 180g black vinyl

• Analog remaster of Sam & Dave’s 1966 debut album

• Jacket: Direct-to-board single pocket

• Inner sleeve: Fidelity Record Pressing–branded poly

• Liner notes, insert, or booklet: None

• Source: Analog; “Lacquers cut from the original analog mono masters”

• Mastering credit: Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, Salina, KS

• Lacquer cut by: Matthew Lutthans at the Mastering Lab, Salina, KS; “MCL” in the deadwax

• Pressed at: Fidelity Record Pressing, Oxnard, CA

• Vinyl pressing quality (visual): A

• Vinyl pressing quality (audio): A

• Additional notes: Comes inside a reusable poly outer sleeve sealed by a hype sticker, as per other Rhino Reserve titles.

Listening equipment:

Table: Technics SL-1200MK2

Cart: Audio-Technica VM540ML

Amp: Luxman L-509X

Speakers: ADS L980